A splenic infarct is caused by occlusion of the splenic artery or one of its branches, resulting in tissue necrosis. They are be caused by a variety of potential pathologies, however fortunately splenic infarctions are rare events.

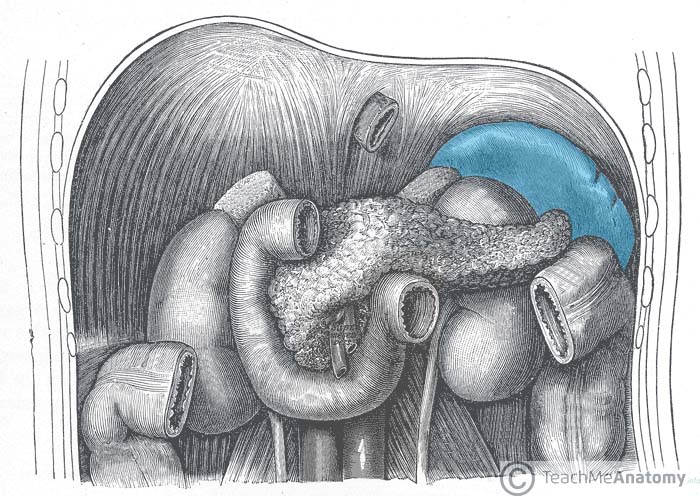

As the spleen is supplied by the splenic artery (from the coeliac axis) and the short gastric arteries (from left gastroepiploic artery), infarction is often not complete due to collateral circulation.

Incidence rates vary significantly, however in predisposing conditions, such as chronic myelogenous leukaemia (CML), rates as high as 72% have been reported, although many of these are asymptomatic.

Aetiology

The most common causes of splenic infarction are haematological disease or thromboembolism.

- Haematological disorders* such as lymphoma, myelofibrosis, Sickle Cell Disease, Chronic Myeloid Leukaemia, Polycythaemia Rubra Vera, or hypercoagulable states

- Embolic disorders such as endocarditis, atrial fibrillation, infected aneurysm grafts, or post-MI mural thrombus

Other rarer causes include vasculitis, trauma (including blunt trauma or torsion of a ‘wandering’ splenic artery), collagen tissue diseases, or surgery (pancreatectomy or liver transplantation).

*Haematological diseases cause infarction through congestion of the splenic circulation by abnormal cells, often further confounded in conditions (such as CML or myelofibrosis) by anaemia and splenomegaly

Clinical Features

Classically, symptomatic patients will present with left upper quadrant abdominal pain, which may radiate to the left shoulder.

Less common symptoms include fever, nausea or vomiting, or pleuritic chest pain. However in a significant number of patients, splenic infarcts can be completely asymptomatic, diagnosed purely by imaging or explorative surgery.

On examination, LUQ tenderness is common. Other signs may be present depending on any complications that may have developed, as discussed below.

Differential Diagnosis

As with many cases of acute abdomen, there is a wide range of differentials to consider, narrowed down through clinical features and investigations.

However, important common differentials to consider for LUQ pain include peptic ulcer disease, pyelonephritis or ureteric colic, and a left sided basal pneumonia.

Investigations

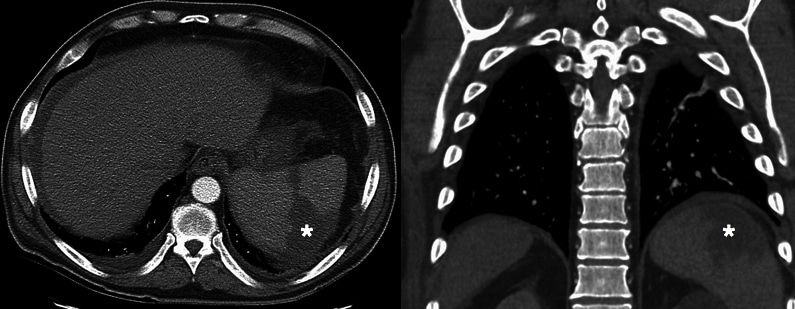

The gold standard investigation for suspected splenic infarction is a CT abdominal scan with IV contrast (Fig. 2).

Routine bloods, including FBC, U&Es, LFTs, and coagulation screen, will aid diagnosis, especially if a haematological or thromboembolic cause is suspected. WCC have been shown to be high in around half of cases and raised d-dimer levels may also aid the diagnosis.

Radiographic Features of Splenic Infarct

As the IV contrast cannot reach the infarcted area, a segmental wedge of hypoattenuated tissue becomes visible on CT scanning, the apex of the wedge pointing to the hilum of the spleen from the segmental branching of the splenic artery.

If the splenic artery, rather than one of its segmental branches, is affected then the entire spleen will be hypoattenuated.

Following treatment, most cases are followed up with repeat CT scanning, which will show either full resolution, fibrosis of the original infarct, or liquefaction of the affected region.

Management

There are no specific treatments for splenic infarct. Patients are monitored regularly, ensuring haemodynamic stability, with appropriate analgesia and IV hydration prescribed. Most cases warrant suitable management of the underlying condition in order to minimise future risk.

It is important to identify the cause of the infarction, which may require the involvement of a haematologist and an ECHO scan, as well as consideration of long term anticoagulation.

Long-term Management

Splenectomy should be avoided due to risks of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) syndrome, however this may become unavoidable if complications develop or symptoms persist. Most cases should be delayed to until patient age >2yrs (ideally >10yrs), to ensure appropriate immune response can be developed post-splenectomy.

Due to the spleens role in the protection against encapsulated bacteria, vaccination against S. pneumoniae, N. mengitidis, and H. influenza is advised in extensive splenic infarctions, as well as long term low dose antibiotic cover (ideally Penicillin V) due to the inability to clear encapsulated bacteria without a spleen.

Prognosis

The prognosis of splenic infarctions varies enormously, depending on the cause and severity of the disease. Patients with benign underlying disease and asymptomatic infarcts will have an extremely good prognosis, whilst patients with splenic infarct secondary to haematological malignancy will have a far more guarded outcome.

Complications

The most common complications of splenic infarction are splenic rupture, splenic abscess, and pseudocyst formation. Most of these cases will warrant splenectomy.

Splenic Abscess

A splenic abscess will be seen post-splenic infarct when underlying cause was from a non-sterile embolus, such as infective endocarditis (or in rarer cases when the patient is immunocompromised)

The embolus seeds infection into the necrotic splenic tissue, yet clinically this can be difficult to differentiate from an uncomplicated infarction. Diagnosis may be based on CT scanning viewed by an experienced radiologist, especially when combined with raised inflammatory markers, however most cases will only be confirmed with explorative surgery.

Auto-Splenectomy

Auto-splenectomy is a rare condition that results in asplenism. Repeated splenic infarctions result in the progressive fibrosis and atrophy of the spleen; when this continues over a prolonged period of time, especially during childhood, this can lead to complete atrophy of the spleen, termed auto-splenectomy.

The most common cause of auto-splenectomy is sickle-cell anaemia. Repeated sickle-cell crises lead to recurrent occlusion of the splenic artery. As this can continue throughout childhood, it can cause complete asplenism by adulthood.

Key Points

- Splenic infarctions are rare events, with most caused by underlying haematological disorder or embolic disease

- Most cases present asymptomatically, being found incidentally on imaging

- Treatment involves managing the underlying cause and ensuring sufficient antimicrobial prophylaxis against encapsulated bacteria

- Complications of splenic infarct include splenic rupture, splenic abscess, and pseudocyst formation