Introduction

Salivary gland tumours are uncommon, making up around 6% of head and neck tumours. They have a wide range of presentations and can be either benign or malignant.

The malignant form will often affect the older patient, whilst benign salivary gland tumours have a peak onset at 40yrs old, with varying proportions between benign and malignant depending on the particular gland involved (Table 1).

|

Benign |

Malignant |

|

| Parotid | 80% | 20% |

| Submandibular | 50% | 50% |

| Sublingual | 20% | 80% |

Table 1 – Proportion of benign and malignant tumours associated with the three main salivary glands

The main benign tumour types are pleomorphic adenoma and Warthin’s tumour (papillary cystadenoma lymphomatosum).

The main malignant tumour types (from most to least common) are mucoepidermoid carcinoma, adenoid cystic carcinoma, acinic cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and adenocarcinoma

Malignant Change

Pleomorphic adenomas can undergo malignant change, termed carcinoma ex-pleomorphic adenoma. They are aggressive and are associated with a poor prognosis.

This occurs in around 2-4% of salivary gland malignancies and should be suspected in cases of sudden rapid growth of a previously stable mass is.

Risk Factors

- Direct radiation exposure

- Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection

- Smoking*

- Genetic alterations (p53 mutations)

*Tobacco smoke has been associated with the development specifically to Warthins tumour

Clinical Features

Individuals will most often present with a slowly enlarging mass, typically painless, in the location of the salivary glands. In malignant lesions, other symptoms can include facial nerve palsy* and overlying erythema or ulceration.

Pain can rarely occur, most often due to suppuration or haemorrhage into the mass, or infiltration of malignancy into surrounding tissue. Indeed, pain should be seen as a red-flag symptom.

Larger salivary malignancies may result in eventual airway obstruction, dysphagia, or hoarseness, whilst salivary tumours protruding into the nasal cavity and paranasal sinuses can present with nasal obstruction or sinusitis.

*Adenoid cystic carcinoma has the greatest tendency to cause perineural invasion, resulting in facial nerve palsy

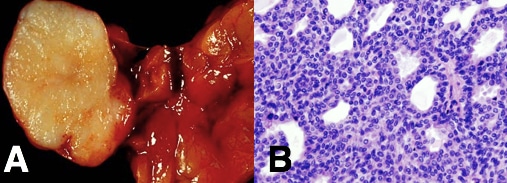

Figure 1 – A parotid tumour (specifically, a pleomorphic adenoma), as seen (A) macroscopically and (B) microscopically

On examination, it is important to perform a bimanual examination of the salivary gland. Assess the lump for tenderness, mobility, and if there are any evidence of cervical lymphadenopathy (salivary gland malignancies tend to spread to lymph nodes in neck level I, II or III).

Examine the oral mucosa (salivary malignancies can invade into the oral mucosa) and remember to assess for any cranial nerve palsy, especially facial nerve palsy.

Differential Diagnosis

Individuals presenting with a salivary mass should be investigated for sialoliathiasis, chronic sialedenitis, autoimmune disease, and lymphoproliferative disorders. In cases where the diagnosis is uncertain, HIV should be considered as well.

Investigations

Routine bloods (FBC, U&Es, and CRP) should be performed, to check for evidence that may indicate an infectious cause.

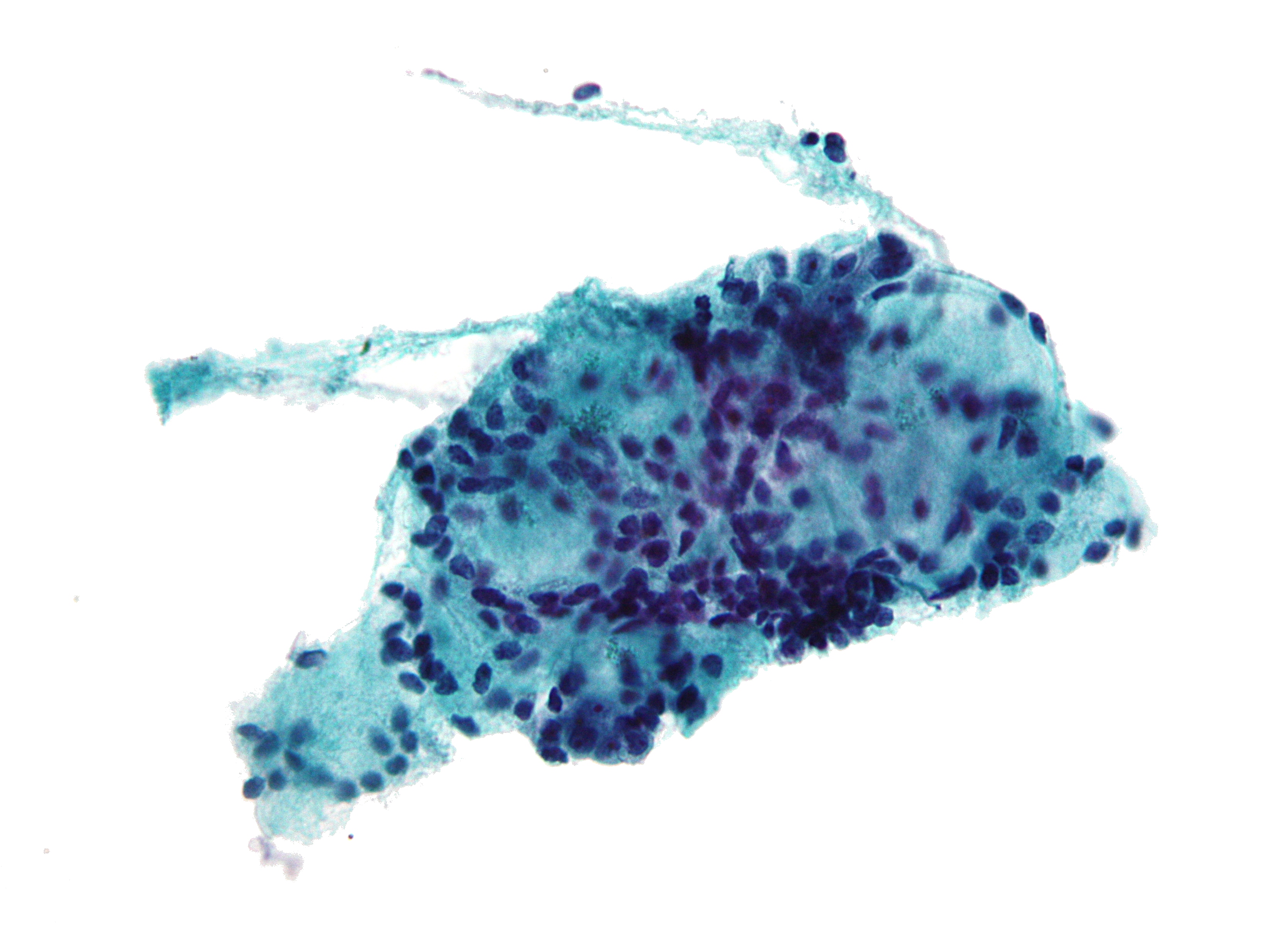

Suspicious lesions should undergo an ultrasound scan (US) with fine needle aspiration cytology (FNA). US will delineate the location, margins, and vascularity of the tumour and FNA will confirm the tumour type.

If malignancy is confirmed, a staging CT scan of neck and thorax is warranted to determine extent of the disease.

Figure 2 – The cytology of an Adenoid Cystic Carcinoma from a FNA

Disease Staging

The TNM staging is used for salivary gland tumours. The five-year survival rate for salivary gland tumours is strongly influenced by the tumour stage (as well as the histological type): T1 – 85% survival; T2 – 66% survival; T3 – 53% survival; T4 – 32% survival

Local metastasis usually to cervical lymph nodes, the highest rate occurring with the mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Distant metastases are most commonly associated with adenoid cystic carcinoma, with the common sites of spread to lung and bone, and as with most malignancies they carry a poor prognosis. Adenoid cystic carcinoma can also recur many years after treatment.

Management

All cases of salivary gland tumours should be discussed with the appropriate multidisciplinary team (MDT), which should be done only at specialist centres.

Surgical Options

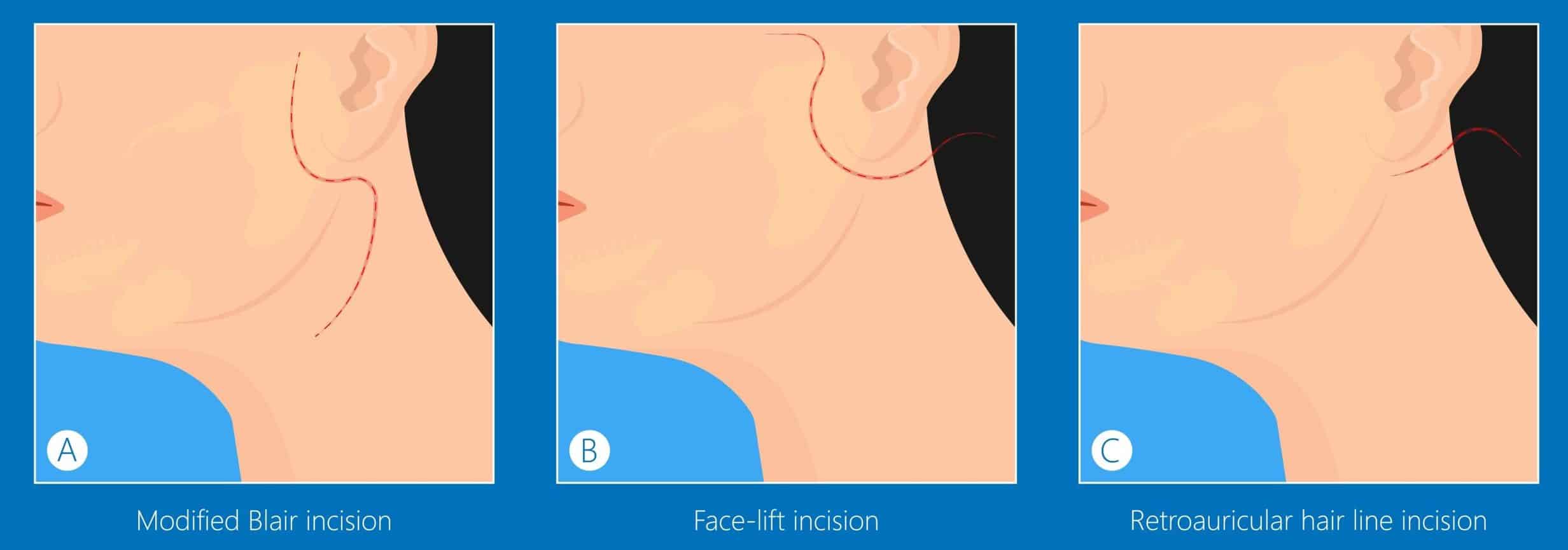

Excision via parotidectomy is the mainstay of most salivary gland tumours, for both benign (due to risk of malignant transformation) and malignant, with malignant tumours warranting more radical procedures*. Where cervical lymphadenopathy is found, selective neck dissection will be performed for lymph node clearance.

*In the case of parotid malignancies with facial nerve involvement, this often requires sacrifice of the facial nerve. A cable graft may then be performed using the great auricular nerve.

Non-Surgical Options

Radiotherapy has been used as adjuvant treatment following surgery (usually for higher-grade tumours) or alone for non-resectable tumours, as has been shown to increase overall survival (especially for advanced high grade adenocarcinoma of the parotid gland).

Indications for post-operative radiotherapy include (1) high-grade or advanced stage tumours (2) residual neck disease (3) recurrent disease (4) adenoid cystic carcinoma (5) close proximity to the facial nerve (6) incomplete or close resection margin

Chemotherapy is not used as neo-adjuvant therapy as salivary gland tumours have a poor response, hence it is only reserved with palliative treatment.

Complications

Early

Haematoma is an important post-operative complication. A rapidly expanding haematoma may cause airway obstruction, hence close observation of these patients post-operatively is paramount.

Facial nerve injury or sacrifice intra-operatively must be included in any consent for the resection procedures*. Transient facial nerve paresis resolves in 3-12 weeks. It is now common practice to use facial nerve monitoring during parotid surgery.

Sialocele is an accumulation of saliva in the space following removal, however most of the time they resolves with conservative management.

*During submandibular gland surgery, the marginal mandibular, hypoglossal and lingual nerve may also be injured

Late

Frey’s syndrome can develop following a parotidectomy, whereby the autonomic fibres supplying the gland reform inappropriately; the stimulus to salivate results in an inappropriate response of redness and sweating.

First bite syndrome is a complication characterised by patient experiencing intense pain on taking the first few bites of a meal, which gradually improves as they eat. It is likely caused by excessive parasympathetic stimulation, causing over-contraction of the myoepithelial cells, secondary to damage to post-ganglionic sympathetic nerves. Treatment with repeated botulinum toxin injections have been shown to be effective.

Prognosis

Prognosis for salivary gland tumours is depended on the pathology. Benign tumours have excellent outcome although pleomorphic salivary adenomas can recur, especially if there is any tumour spillage during surgery.

Key Points

- Salivary gland tumours make up around 6% of head and neck tumours, with the malignant form more common with increasing age

- Most cases present as a painless enlarging mass

- All suspicious lesions should undergo an ultrasound scan with fine needle aspiration cytology for further evaluation

- Excision is the mainstay of most salivary gland tumours, with radiotherapy used either as adjuvant treatment or alone for non-resectable tumours