Introduction

A diverticulum is an outpouching of the bowel wall. They are most commonly found in the sigmoid colon, but can be present throughout the large and small bowel.

There are four different manifestations of the condition:

- Diverticulosis – the presence of diverticula (asymptomatic, incidental on imaging)

- Diverticular disease – symptoms arising from the diverticula

- Diverticulitis – inflammation of the diverticula

- Diverticular bleed – where the diverticulum erodes into a vessel and causes a large volume painless bleed

Diverticulosis is present in around 50% of >50yrs and 70% of >80yrs, but only 25% of these cases become symptomatic. The disease affects men more than women and is more prevalent in developed countries.

Pathophysiology

In an aging bowel that has naturally become weakened over time, the movement of stool within the lumen will cause an increase in luminal pressure. This results in an outpouching of the mucosa through the weaker areas of the bowel wall (at the junctions of the triangular muscle sheets and blood vessels penetrate to supply the bowel wall).

Bacteria can overgrow within the outpouchings, leading to inflammation of the diverticulum (diverticulitis) which can sometimes perforate, potentially leading to diffuse peritonitis sepsis and death. In chronic cases, fistulae can form, most commonly colovesical or colovaginal.

Diverticulitis is classified as either simple or complicated. Complicated diverticulitis refers to abscess presence or free perforation, whilst simple diverticulitis describes inflammation without these features.

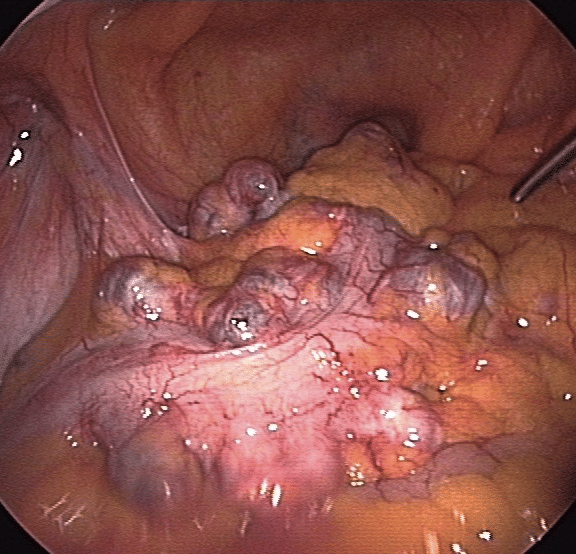

Figure 1 – Laparoscopic view of diverticula in the sigmoid colon

Risk Factors

The risk factors for the formation of diverticulum include age, low dietary fibre intake, obesity, smoking, family history, and NSAID use.

Clinical Features

A large proportion of individuals with diverticulosis remain asymptomatic and are only found incidentally, such as during routine colonoscopy or CT imaging. These are often of no clinical significance. However, patients can present with diverticular disease, diverticulitis, or a diverticular bleed

Diverticular Disease

Features of diverticular disease include an intermittent lower abdominal pain, typically colicky in nature and may be relieved by defecation.

Other symptoms include an altered bowel habit, associated nausea, and flatulence. There will be no systemic features present.

Acute Diverticulitis

Acute diverticulitis however will present with acute abdominal pain*, typically sharp in nature and normally localised in the left iliac fossa, worsened by movement. On examination, there will be localised tenderness, alongside features of systemic upset, such as decreased appetite, pyrexia, or nausea.

A perforated diverticulum will present with signs of localised peritonism or generalised peritonitis. These patients are frequently extremely unwell and the condition can be fatal.

*If a patient is taking corticosteroids or immunosuppressants, this can mask the symptoms of diverticulitis, even if perforated; in patients with a redundant sigmoid colon, pain may often be in the right lower quadrant or suprapubic area

Diverticular Abscess

A diverticular abscess (often termed a pericolic abscess) occurs as a sequelae in complicated diverticulitis

Those that are around <5cm can generally be managed with conservatively with intravenous antibiotics, as this is effective in ~90% of cases. If the abscess is any bigger, then radiological drainage is first-line treatment.

Complicated multi-loculated abscesses (or patients who clinically deteriorate) will need surgical intervention, either with a laparoscopic washout or a Hartmann’s procedure.

Differential Diagnosis

The important differential diagnoses for patients presenting with lower abdominal pain and bowel symptoms are inflammatory bowel disease, bowel cancer, or appendicitis.

Other causes of abdominal pain should also be sought including mesenteric ischaemia, gynaecological causes, or renal stones.

Investigations

Laboratory Tests

Any patient presenting acutely with suspected diverticular disease should have initial routine blood tests performed, including FBC, CRP, and U&Es. Those with suspected diverticulitis, should also have a Group and Save (in case surgical intervention is required) and a venous blood gas (VBG). A urine dipstick may prove helpful to exclude any urological causes.

Imaging

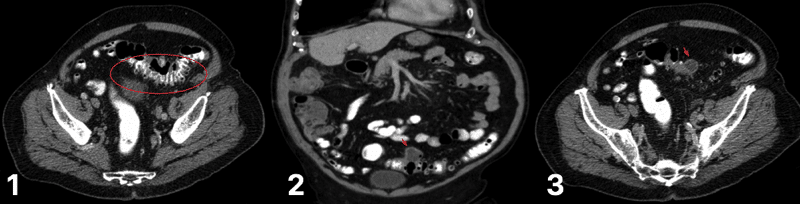

For cases of suspected diverticulitis, a CT abdomen-pelvis scan (Fig. 2) is the investigation of choice. CT findings that can suggest diverticulitis include thickening of the colonic wall, pericolonic fat stranding, abscesses, localised air bubbles, or free air.

*Colonoscopy should never be performed in any presenting cases of suspected diverticulitis, due to the increased risk of perforation

Figure 2 – CT scan for varying degrees of diverticular disease (1) diverticulum in the sigmoid colon (2) degree of diverticulitis present (3) abscess formation, secondary to ongoing diverticulitis

In patients with suspected uncomplicated diverticular disease, a flexible sigmoidoscopy* is a good initial approach as this will identify any obvious rectosigmoidal lesion. If the patient is not a suitable candidate for endoscopy, CT colonography is an alternative option.

Disease Staging

Acute diverticulitis can be staged using the Hinchey Classification, a classification system based on CT findings. It can be used to aid clinical management; higher stages are associated with higher morbidity and mortality.

| Stage | Computed Tomography Description |

| Stage 1 | Phlegmon (1a) or diverticulitis with pericolic or mesenteric abscess (1b) |

| Stage 2 | Diverticulitis with walled off pelvic abscess |

| Stage 3 | Diverticulitis with generalised purulent peritonitis |

| Stage 4 | Diverticulitis with generalised faecal peritonitis |

Table 1 – Hinchey Classification of Acute Diverticulitis

Management

Diverticular Disease

Patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease can often be managed as an outpatient* with simple analgesia and encouraging oral fluid intake. Outpatient colonoscopy should be arranged to exclude any masked malignancies.

Patients with diverticular bleeds can often be managed conservatively (as discussed here) as most cases will be self-limiting*. Any significant bleeding will need appropriate resuscitation, including the use of blood products, and stabilisation.

Those that fail to respond to conservative management may warrant embolisation or surgical resection. Indeed, if a second bleeding episode occurs there is a significant chance of further episodes (up to 50%)

*Hospital admission may be required in cases of uncontrolled pain, concerns of dehydration, significant co-morbidities or immunocompromise, significant PR bleeding, or symptoms persisting for longer than 48 hours despite conservative management.

Acute Diverticulitis

Most patients with acute diverticulitis can be managed conservatively, with antibiotics, intravenous fluids, and analgesia. Indeed, young patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis can be considered for ambulatory management, especially if the patient is systemically otherwise well and no significant co-morbidities or immunosuppression*.

In diverticulitis complicated by perforation with pericolic gas and localised abscess formation only, trialing conservative management with antibiotics can be safely recommended if the patient is stable. If the abscess is >5cm, percutaneous drainage (IR) should be attempted if accessible. These patients need to be closely monitored, with treatment escalated if there is clinical deterioration or no improvement.

In uncomplicated cases, symptoms typically begin to improve within 2-3 days after the initiation of treatment for uncomplicated cases. Clinical deterioration (or a lack of improvement) should prompt repeat imaging to check for disease progression / complication. Oral intake should be encouraged where possible.

*Currentlguidelines state that in immunocompetent patients with uncomplicated diverticulitis with no systemic features of inflammation, antibiotics should not be routinely given initially.

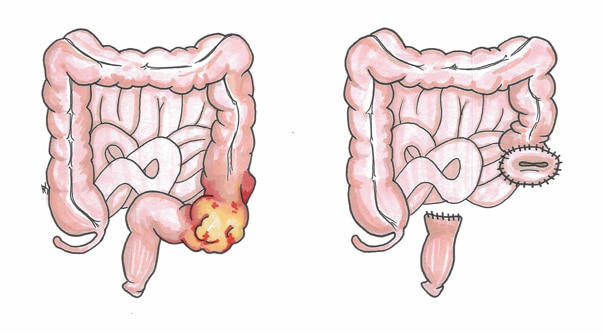

Surgical Management

Surgical intervention* is usually required in those with perforation with diffuse purulent or faecal peritonitis or overwhelming sepsis. This is a major procedure and usually involves a Hartmann’s procedure (a sigmoid colectomy with formation of an end colostomy. Fig. 3)*

Other interventions include resection with primary anastomosis or laparoscopic peritoneal lavage:

- A sigmoid resection with primary anastomosis +/- defunctioning loop ileostomy can be attempted if the patient is stable, has limited co-morbidities, and a proficient surgeon

- Laparoscopic peritoneal lavage can be beneficial in a select group of patients (e.g. frail patients not suitable for a resection, those with abscess not amenable to percutaneous drainage, or those not improving on antibiotics alone

*Whilst reversal of the colostomy may be possible at a later date, this only occurs in ~50% of cases

Complications

Recurrence of diverticulitis after first episode is around 10-35%. Elective segmental resection may be performed in patients with recurrent disease.

Complications of develop in severe, recurrent, or chronic cases of the condition, the most common being stricture formation or fistula formation.

Diverticular Stricture

A patient can develop a diverticular stricture following repeated episodes of acute inflammation. The bowel becomes scarred and fibrotic, resulting in a benign stricture.

This can result in a large bowel obstruction. In such cases, a sigmoid colectomy is required, either electively or urgently, depending on the presentation (colonic stenting can be used as a temporising measure, however surgery will eventually be required).

Fistula Formation

Due to the repeated inflammation, fistula can form secondary to diverticulitis, which will nearly always require surgical intervention. The most common types are:

- Colovesical fistula form between the bowel and the bladder

- Generally present with recurrent urinary tract infections, pneumoturia (gas bubbles in the urine), or passing faecal matter in the urine

- Colovaginal fistula form between the bowel and the vagina

- Generally present with copious vaginal discharge or recurrent vaginal infections

Key Points

- The four different manifestations of diverticula are diverticulosis, diverticular disease, diverticulitis, and diverticular bleeds

- Most cases of uncomplicated diverticulitis can be treated conservatively

- Surgical intervention is warranted in those with evidence of perforation, sepsis not responding to antibiotic therapy, or failure to improve despite conservative management

- The most common complications of diverticular disease are stricture formation and fistula formation