Introduction

A perianal fistula (fistula-in-ano) refers to an abnormal connection between the anal canal and the perianal skin.

The majority are associated with anorectal abscess formation, with one third of patients with an anorectal abscess having an associated perianal fistula at the time of presentation.

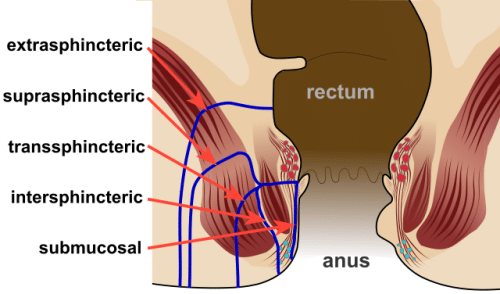

The Park’s Classification System divides anal fistulae into four distinct types (Fig. 1); inter-sphincteric fistula (most common), trans-sphincteric fistula, supra-sphincteric fistula (least common), and extra-sphincteric fistula.

Figure 1 – Diagram highlighting the positions and nomenclature for anorectal fistulae

Aetiology

The formation of a perianal fistula typically occurs as a consequence of an anorectal abscess. However, other risk factors for their formation include:

- Inflammatory bowel disease, mainly perianal Crohn’s Disease

- Systemic diseases, typically Diabetes Mellitus

- History of trauma to the anal region

- Previous radiation therapy to the anal region

Clinical Features

Anal fistulae usually present with either recurrent perianal abcesses, or intermittent or continuous discharge per rectum, including mucus, blood, pus, or faeces.

On examination, an external opening on the perineum may be seen; these can be fully open or covered in granulation tissue. A fibrous tract may be felt underneath the skin on digital rectal examination.

The Goodsall Rule

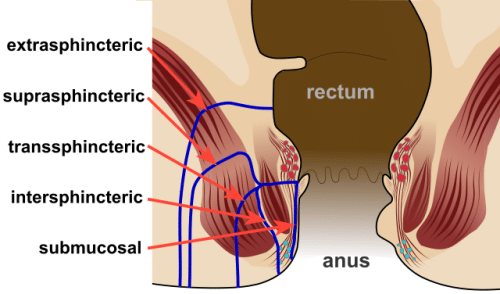

The Goodsall rule can be used clinically to predict the trajectory of a fistula tract, depending on the location of the external opening (Fig. 2):

- External opening posterior to the transverse anal line – fistula tract will follow a curved course to the posterior midline

- External opening anterior to the transverse anal line – fistula tract will follow a straight radial course to the dentate line

Figure 2 – The Goodsall rule, used clinically to predict the course of a fistula tract

Investigations

Outside of the emergency setting (i.e. anorectal abscess), the majority of fistula are investigated initially with MRI imaging, used to visualise the anatomy of the tract. Any surgical intervention can then be planned based on this.

Management

The definitive management for an anal fistula depends largely on the cause and site*, with varying surgical options available.

*For those due to perianal Crohn’s disease (following drainage of any perianal abscess present), medical management of the Crohn’s disease is often started first prior to further surgical intervention

Surgical Treatment

The most common surgical methods employed are:

- A fistulotomy (suitable for superficial disease) involves laying the tract open by cutting through skin and subcutaneous tissue, allowing it to heal by secondary intention

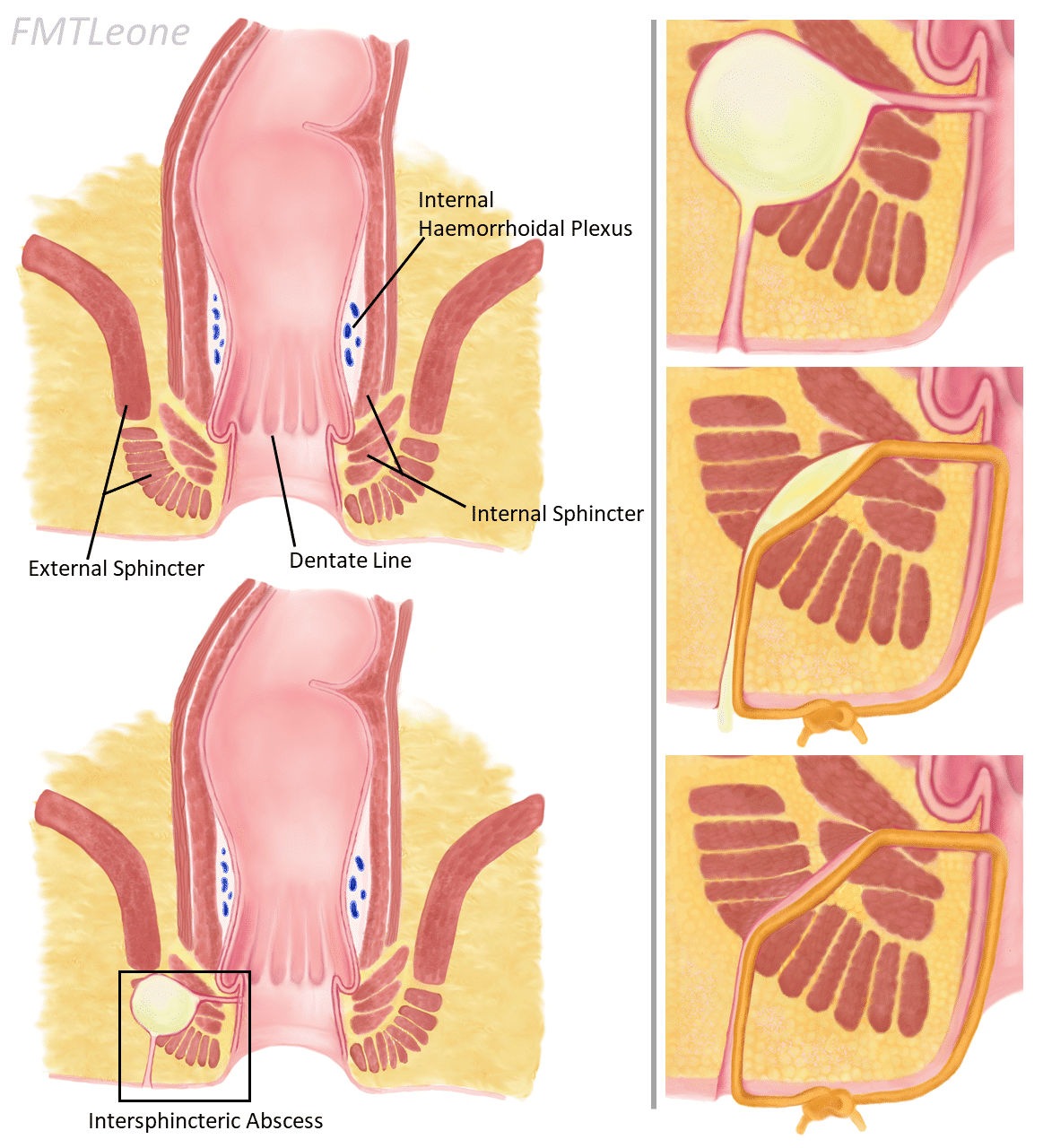

- The placement of a seton (suitable for higher tract disease) through the fistula attempts to keep the tract open, thus draining any existing abscess as well as prevent recurrent formation of abscesses (Fig. 3)

- Fibrin glue or bioprosthetic plugs can also be used to seal fistulae, if appropriate

Other more specialist methods for treating fistulae include endorectal advancement flap surgery, endoscopic ablation, or laser surgery.

A Cochrane Review concluded that there is no difference in recurrence rates between the various techniques used in the surgical treatment for anal fistulae, but the choice of intervention is mainly determined by the course of the tract*. It is quite common for patients with complex anal fistulas to require several repeat procedures over subsequent months.

*If the fistula has a low track course (whereby the tract travels through less subcutaneous tissue and muscle) faecal continence is rarely impaired post-operatively, however if the fistula has a high tract course then there is a higher chance of impairment in continence

Figure 3 – A seton passing through a perianal fistula, thereby allowing the localised infection to drain and the tract to slowly heal

Key Points

- An anal fistula is an abnormal connection between the anal canal and the perianal skin

- MRI pelvis scan is the mainstay of initial investigation

- There are multiple surgical management options available, depending on the tract anatomy