Introduction

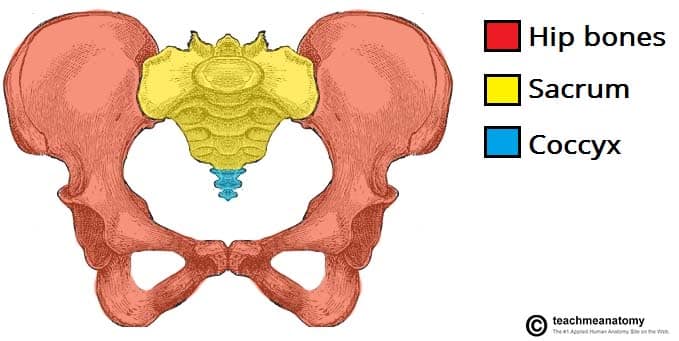

The pelvic ring is formed by the two innominate bones (ilium, ischium and pubis) and the sacrum, and their supporting ligaments.

The true pelvis contains the rectum, bladder and uterus in females, as well as the iliac vessels and the lumbosacral nerve roots. As such, pelvic fractures can be associated with life-threatening haemorrhage, neurological deficit, urogenital trauma, and bowel injury.

Pelvic ring injuries can be caused by both high and low energy mechanisms, with damage occurring either at bony or ligamentous points.

This article will mainly focus on the clinical assessment and management of high energy pelvic injuries.

Clinical Features

Pelvic ring injuries are most often caused by high energy blunt trauma, such as road traffic accidents or falls from height*. As such, they typically occur with concurrent injuries.

Patients with pelvic fractures may have an obvious deformity to their pelvis. There will be significant pain and swelling around the pelvis.

When a pelvic fracture is suspected, a full neurovascular assessment of the lower limbs is required, including checking anal tone, as sacral nerve roots and iliac vessels can frequently be injured.

Other pathologies that can occur in pelvic fractures that need assessment in the initial trauma survey include abdominal injuries, urethral injuries, and open fractures (this includes “internal open fractures” into the rectum or vaginal vault). It is also important to look for any surrounding ecchymosis or developing haematoma present (e.g. perineal, scrotal or labial).

*In the elderly, pelvic injuries often occur after a fall from standing height, including as fractures of the pubic rami or sacral compression fracture; rarely, more complex pelvic fractures can occur, especially in osteoporotic bone.

Differential Diagnosis

The high energy nature of this injuries means that it is important to look for trauma elsewhere, ensuring to check the head, chest, spine, and long bones. Concurrent acetabular fractures can also occur.

Low Energy Pelvic Fractures

Low-energy injuries in young patients are typically avulsion fractures, reported as a sudden severe pain, poorly localised to the hip/pelvis, felt whilst performing a rapid, powerful movement, such as starting to run.

The most commonly affected sites are the anterior superior iliac spine (sartorius), anterior inferior iliac spine (rectus femoris), and the ischial tuberosity (hamstring muscles). Avulsion fractures are often managed conservatively unless there is significant displacement of the fragment.

Investigation

Any patient presenting following a high-energy injury with suspected pelvic fracture must be assessed and managed as per ATLS guidelines.

As a minimum, 3 plain film radiographs (Fig. 2) are required to completely assess the pelvic ring (anterior-posterior, inlet view, and outlet view). However, in the trauma setting, often a CT scan is performed as part of the patient assessment, which usually negates the need for plain films.

Figure 2 – Plain film radiograph showing an “open book” pelvic fracture

Classification

Two classification systems are commonly used to describe pelvic ring injuries:

- Young and Burgess classification – groups based on the vector of the disrupting force and the resulting degree of displacement (see Appendix)

- Antero-posterior compression (APC 1-3)

- Lateral compression (LC 1-3)

- Vertical shear (VS 1-2)

- Tile classification – fractures grouped based on the stability of the pelvic ring

- A-type fractures = rotationally and vertically stable

- B-type fractures = horizontally unstable but vertically stable

- C-type fractures = both horizontally and vertically unstable

The Denis classification can be used to classify fractures of the sacrum; it describes the line of the fracture in relation to the sacral foramina, with type 1 = lateral to the foramina, type 2 = transforaminal, type 3 = medial to the foramina. In addition, a transverse component may result in an H-shaped or U-shaped fracture pattern.

Management

Initial management of a patient with high energy trauma follows the ATLS guidelines and should always begin with a primary survey to identify life-threatening injuries

Pelvic injuries can cause a significant amount of blood loss (most commonly from the retroperitoneal venous plexus or intraabdominal), resulting in hypovolaemic shock. Any hypotensive patient with a history of pelvic trauma should be assumed to have a pelvic fracture until proven otherwise and a pelvic binder should be applied to give skeletal stabilisation (required for attempted clot formation).

Figure 3 – Trauma patients with suspected pelvic injury need to be managed as per ATLS guidelines

Operative Management

Definitive management of pelvic fractures can be conservative or operative.

The need for immediate surgery will depend on the patient’s response to initial resuscitation, with the haemodynamically unstable patient possibly requiring interventional radiology or trauma laparotomy +/- retroperitoneal packing.

Indications for operative management include life threatening haemorrhage, unstable fractures, open fractures, and associated fractures with an associated urological injury. The approach and method of stabilisation can be guided by the Young and Burgess classification* and involves a combination of anterior and posterior stabilisation.

*APC1 and LC1 type fractures are stable and can usually be managed conservatively with good analgesia and mobilising as pain allows, however surgery may be required if there are ongoing symptoms

Complications

Complications following pelvic fractures include urological injury (more common in men), venous thromboembolism (DVT in ~60% and PE in ~25%, therefore prophylaxis is essential), and long-standing pelvic pain.

Key Points

- Pelvic fractures can occur following high-energy or low-energy injuries, and often associated with concurrent injuries

- Due to nearby viscera, they can be associated with life-threatening haemorrhage, neurological deficit, urogenital trauma, and bowel injury

- The Young and Burgess classification is the most commonly used classification for pelvic fractures

- Diagnosis is made via plain film radiographs or CT imaging

- Definitive management of pelvic fractures can be conservative or operative, and the need for immediate surgery will depend on the patient’s response to initial resuscitation

- Complications following pelvic fractures include urological injury, venous thromboembolism, and long-standing pelvic pain

Appendix

|

The Youngs-Burgess Classification for Pelvic Fractures |

|

|

Antero-Posterior Compression (APC) |

|

| APC 1 | Disruption of the pubic symphysis, diastasis <2.5cm, posterior ligamentous structures of pelvis are intact |

| APC 2 | Disruption of the pubic symphysis, diastasis >2.5cm, disruption of the sacrospinous, sacrotuberous, and anterior sacroiliac ligaments |

| APC 3 | As with APC 2, but the posterior sacroiliac injury is complete, often indistinguishable from a VS fracture |

|

Lateral Compression (LC) |

|

| LC 1 | Transverse / oblique fracture of the pubic ramus, often in association with a crush fracture of the ipsilateral sacral ala |

| LC 2 | Rami fracture and fracture of the iliac blade, resulting in a ‘crescent fragment’ |

| LC 3 | As with a LC 2 fracture but the contralateral iliac wing opens up. Produces a ‘windswept pelvis’ |

|

Vertical Shear (VS) |

|

| VS 1 | Unilateral complete loss of attachment between the sacrum and the lower limb |

| VS 2 | As with VS 1 but the injury is bilateral |