Introduction

Galactorrhoea is defined as is defined as copious, bilateral, multi-ductal, milky discharge, not associated with pregnancy or lactation.

Galactorrhoea occurs almost exclusively in females and most commonly in adults, however rarely may be seen in male infants secondary to maternal oestrogen exposure.

In postpartum females, this also includes milk production occurring 6-12 months after pregnancy and the cessation of breastfeeding

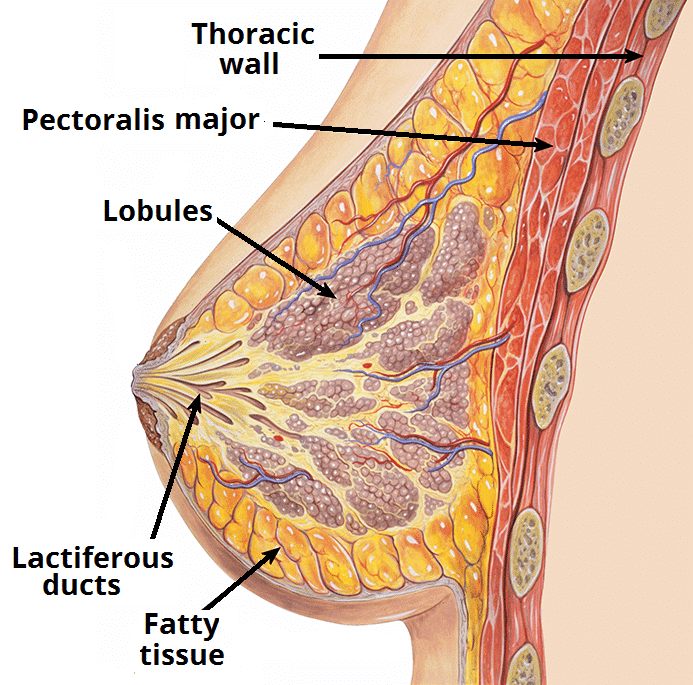

Figure 1 – The internal structure of the breast

Lactation Physiology

Lactation is predominantly regulated by the hormone prolactin, a polypeptide hormone which is produced and secreted by the anterior pituitary gland.

Prolactin secretion is controlled by dopamine, released by the hypothalamus, acting to inhibit prolactin secretion. Actions of TRH and oestrogen conversely act to stimulate the release of prolactin from the pituitary.

Aetiology

Hyperprolactinaemia is the most common cause. Causes of hyperprolactinaemic galactorrhoea include:

- Idiopathic, occurring in around 40% cases

- Pituitary Adenoma, whereby benign tumours of the pituitary gland can secrete excessive prolactin hormone, often termed prolactinomas

- Drug-Induced, with medications such as SSRIs, anti-psychotics, or H2-antagonists all stimulating prolactin release

- Neurological, whereby neurogenic pathways are activated to inhibit dopamine levels, such as varicella zoster infection or spinal cord injury

- Hypothyroidism, as elevated thyrotropin-releasing hormone can also stimulate prolactin related.

- Cushing’s disease, Acromegaly, and Addison’s disease have also been associated with the condition.

- Renal failure or liver failure

- Damage to the pituitary stalk, leading to reduced dopamine inhibition to the pituitary, from surgical resection, multiple sclerosis, sarcoidosis, or tuberculosis

Normoprolactinaemic galactorrhoea is less common and is typically idiopathic, the diagnosis only being made once all other causes of galactorrhoea have been excluded (i.e. normal blood markers and regular menstruation). These patients can often safely be reassured and observed.

Clinical Features

It is important to determine the presence of true galactorrhoea* (multi-ductal milky white nipple discharge, typically bilateral), not alternative nipple discharge that could signal an alternative diagnosis.

Clarify any additional features, such as breast lumps, mastalgia, and their last menstrual period, to assess for potential underlying causes or an alternative diagnosis. Ask about features of endocrine disease and for neurological symptoms (headaches, visual disturbances)

Ensure to take an adequate drug history, including any form of contraception, over the counter medication, or recreational drug use.

Breast examination is often unremarkable. Check for any visual changes (suggestive of compressive pituitary masses) or features of hypothyroidism.

*A Sudan IV stain for fat droplets in the discharge can be used to confirm galactorrhoea, however is rarely used in clinical practice.

Investigations

It is essential to exclude pregnancy in all females within the reproductive age range.

Patients should have serum prolactin levels* checked, with complete thyroid function, liver function, and renal function tests. If the history and clinical examination suggests such, further endocrine tests (IGF-1, ACTH etc.) may be warranted.

If a pituitary tumour (or parasellar pathology) is suspected, a MRI head with contrast is required for further assessment. Breast imaging may be warranting if any palpable lumps or lymph nodes present.

*Prolactin levels >1000 mU/L, in the absence of any drug cause, suggests a prolactinoma

Management

Optimal management of galactorrhoea is determined by identifying and treating the underlying cause.

Patients with confirmed pituitary tumours can be started on dopamine agonist therapy (such as Cabergoline and Bromocriptine) and referred to neurosurgery for assessment for potential trans-sphenoidal surgery.

Idiopathic normoprolactinaemic galactorrhoea often resolves spontaneously, however if persistent can also be trialled with low-dose dopamine agonist.

Those with troublesome galactorrhoea who are intolerant of medication, bilateral total duct excision may be required.

Key Points

- The usual mechanism for galactorrhea is from hyperprolactinaemia

- Bilateral multi-ductal milky white nipple discharge is characteristic and staining of the discharge can confirm diagnosis.

- It is essential to rule out pregnancy with a B-hCG test in appropriate females.

- Treatment of prolactinoma by an endocrinologist commonly involves dopamine agonist therapy and eventually transphenoidal surgery will be considered