Introduction

A peptic ulcer is a break in the lining of the gastrointestinal tract, extending through to the muscular layer (muscularis mucosae) of the bowel wall.

They are most often located on the lesser curvature of the proximal stomach or the first part of the duodenum.

Whilst rates are declining in many high-income countries, due to improved identification and treatment of H. pylori, current prevalence rates are between 1-2%.

In this article, we shall look at the clinical features, investigations and management of uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease. Cases of haematemesis, perforation, or gastric outlet obstruction secondary to peptic ulcer disease are discussed elsewhere on the site.

Aetiology

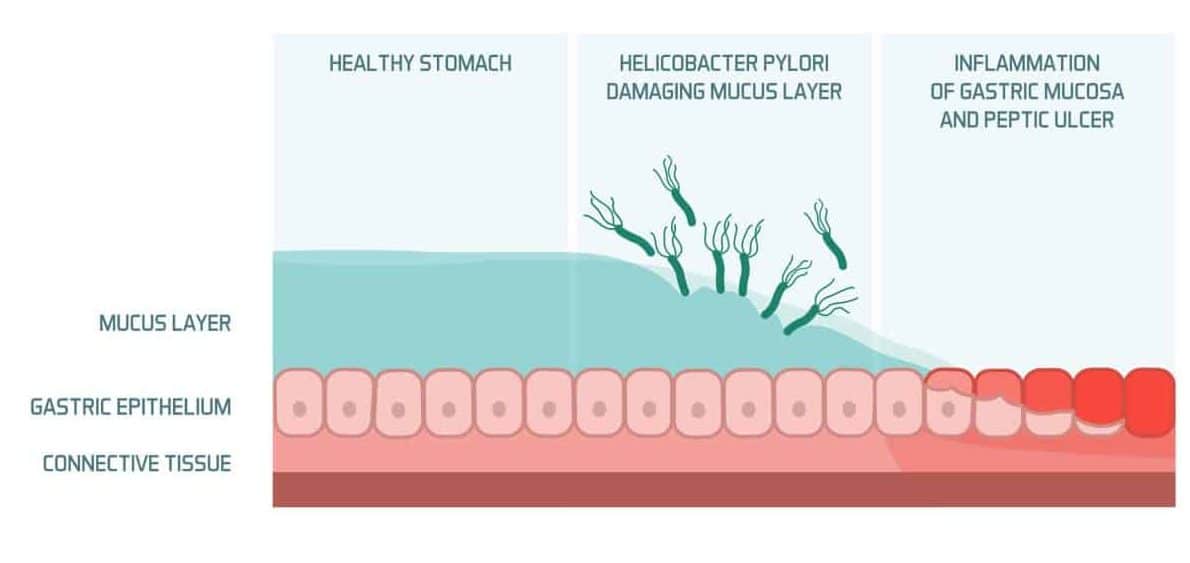

The normal gastrointestinal mucosa is protected by numerous defensive mechanisms, such as surface mucous secretion and HCO3– ion release.

Peptic ulcer disease occurs when there is an imbalance between the factors protecting the mucosa and those causing damage to it. Most commonly, this is through the presence of Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) or Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drug (NSAID) use:

- H. pylori can survive in the gastric and duodenal mucosa by producing an alkaline micro-environment, then subsequently induces an inflammatory response in the mucosa, leading to eventual ulceration (Fig. 2)

- NSAIDs can cause peptic ulcer formation by their action in inhibiting prostaglandin synthesis, resulting in a reduced secretion of glycoprotein, mucus, and phospholipids by the gastric epithelial cells

Risk Factors

The two main risk factors for peptic ulcers are H. pylori infection and prolonged NSAID use.

Other risk factors include corticosteroid use (when used with NSAIDs), previous gastric bypass surgery, physiological stress (such as severe burns (Curling’s ulcer) or head trauma (Cushing’s ulcer)), or Zollinger-Ellison syndrome (rare, see below).

Helicobacter Pylori

H. pylori are Gram negative spiral-shaped bacillus, found in the mucous layer of those with duodenal ulcers (90%) or gastric ulcers (70%).

They survive in the stomach and duodenum by producing an alkaline micro-environment, inducing an inflammatory response in the mucosa, leading to eventual ulceration by:

- Invoking a cytokine and interleukin-driven inflammatory response

- Increasing gastric acid secretion by inducing the release of histamine that acts on the gastric parietal cells

- Damaging host mucous secretion by degrading surface glycoproteins and down-regulating bicarbonate production

Clinical Features

Up to 70% of patients with peptic ulcers can be asymptomatic.

For symptomatic patients, peptic ulcers can present with epigastric pain associated with eating; classically, gastric ulcer pain is exacerbated immediately after eating, whilst duodenal ulcer pain is worse 2-4 hours after eating (or even alleviated by eating)

Other symptoms can include nausea, bloating, dyspepsia, or early satiety. Less commonly, patients may present with complications of their peptic ulcer disease, such as haematemesis, perforation, or gastric outlet obstruction.

In uncomplicated cases, examination is typically unremarkable.

Differential Diagnoses

Any condition that causes dyspepsia, chest pain, or epigastric pain can be considered a differential for peptic ulcer disease.

Important differentials to consider include ischaemic heart disease, gastro-oesphageal reflux disease, gallstone disease, and upper GI malignancies.

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome

Zollinger-Ellison Syndrome refers to a triad of (i) severe peptic ulcer disease (ii) gastric acid hypersecretion and (iii) gastrinoma. The characteristic finding is a fasting gastrin level of >1000 pg/ml.

A third of these cases are discovered as part of Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia Type 1 syndrome (Pancreas / Pituitary / Parathyroid tumours), so further investigations for MEN syndrome are often warranted.

Investigations

In patients with clinical features suggestive of peptic ulcer disease, in the absence of red flag symptoms, can be treated empirically initially.

Patients should undergo non-invasive H. pylori testing, such as a carbon-13 urea breath test or a stool antigen test. Those who test positive for H. pylori should be started on triple therapy (see below).

Red flag symptoms, as outlined by NICE guidance, include:

- New-onset dysphagia

- Aged >55 years with weight loss and either upper abdominal pain, reflux, or dyspepsia

- New onset dyspepsia not responding to PPI treatment

Endoscopy

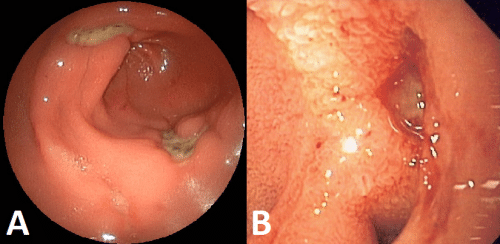

In patients with red flag symptoms or those with ongoing symptoms despite empirical treatment, an upper GI endoscopy (OGD) is required.

At endoscopy, any peptic ulceration seen (Fig. 3) can be biopsied, which will be sent for histology (if looks suspicious for malignancy) and for rapid urease test (CLO test) to determine the presence of H. pylori. A repeat endoscopy should be performed towards the end of PPI therapy to check for its resolution.

Endoscopic therapy can also be utilised in cases of upper GI bleeding, secondary to peptic ulcer disease.

Management

Any patient with peptic ulcer disease should be given lifestyle advice to reduce symptoms, such as smoking cessation, weight loss, and reduction in alcohol consumption. There should also be an avoidance of NSAIDs where possible.

Patients with suspected or confirmed ulcers can be started on a Proton Pump Inhibitor (PPI, e.g. omeprazole) for 4-6 weeks to reduce acid production. They should be reassessed after this period for resolution of symptoms (“Test and Treat”).

Those patients with a positive H. pylori test should be started on triple therapy. Whilst local guidance for this will vary, this commonly consists of PPI therapy with oral amoxicillin and clarithromycin or metronidazole for 14 days.

Surgery for uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease is rare. In severe or relapsing disease, either partial gastrectomy or selective vagotomy may be considered

Complications

The main complications of peptic ulcer disease are bleeding, perforation, or gastric outlet obstruction.

Key Points

- Patients with peptic ulcer disease often have epigastric pain, associated with eating

- pylori and NSAIDs are the most common causes for peptic ulcer disease

- Conservative management, through lifestyle changes and proton pump inhibitors, is the mainstay of treatment in most cases

- Any patient with red-flag symptoms or not responding to conservative management should be referred for urgent upper GI endoscopy

- Surgical management of uncomplicated peptic ulcer disease is rare