Introduction

Post-operative haemorrhage is a common complication that can occur after any surgical procedure.

In this article, we shall look at the types of haemorrhage, their clinical features, and their management.

Classification

Haemorrhage in the surgical patient can be classified into 3 main categories:

- Primary bleeding – bleeding that occurs within the intra-operative period

- This should be resolved during the operation, with any major haemorrhages recorded in the operative notes and the patient monitored closely post-operatively

- Reactive bleeding – occurs within 24 hours of operation

- Most cases of reactive haemorrhage are from a ligature that slips or a missed vessel; these vessels can often be missed intraoperatively due to intraoperative hypotension and vasoconstriction, meaning only once the blood pressure normalises post-operatively will this bleeding occur

- Secondary bleeding – occurs 7-10 days post-operatively

- Secondary haemorrhage is often due to erosion of a vessel from a spreading infection, such as when a heavily contaminated wound is closed primarily

In physiological response to bleeding, initially localised and splanchnic vasoconstriction will occur, before activation of the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system, in attempt to maintain blood pressure. However, with ongoing bleeding and hypovolaemia, blood pressure will not be able to be maintained unless the bleeding is stopped and the volume lost is replaced.

Clinical Features and Assessment

Clinical features of haemorrhagic shock* include tachycardia, dizziness, agitation, a raised respiratory rate, or a decreased urine output. Any external bleeding from a wound or drain will also be evident.

Examination of the patient should include a thorough exposure looking for bleeding, followed by systematic palpation of the surgical area looking for swelling, discoloration, disproportionate tenderness, and any peritonism (in abdominal cases). Review the observations and assess any degree of shock (see Table 1).

*Hypotension is often a late sign, it is important to not assume a patient is not bleeding just because their blood pressure is normal

| Class I | Class II | Class III | Class IV | |

| Blood Loss (ml) | <750ml | 750-1500ml | 1500-2000 | >2000 |

| Blood Loss (%) | <15% | 15-30% | 30-40% | >40% |

| Heart Rate | <100 | 100-120 | 120-140 | >140 |

| Blood Pressure | Normal | Normal | Decreased | Decreased |

| Respiratory Rate | 14-20 | 20-30 | 30-40 | >40 |

| Urine Output (mL/hr) | >30 | 20-30 | 5-20 | <5 |

Table 1 – Classification of Haemorrhagic Shock

Management

If there is a clinical suspicion of post-operative bleeding, fast and efficient initial management will reduce overall morbidity and mortality. An A to E approach is advised, taking particular care to ensure adequate intravenous access and rapid fluid resuscitation.

Make sure to read the operation notes, clarifying the type of surgery and the location of wounds, drains, or areas of importance. Ensure to apply direct pressure to the bleeding site (if visible) and ensure to obtain urgent senior surgical review with appropriate imaging arranged as necessary.

Urgent blood transfusion should be considered in the case of moderate to severe post-operative haemorrhage. If severe bleeding, this should be in the form of red blood cells, platelets, and fresh frozen plasma, with a major haemorrhage protocol activated as necessary

Upon review with a senior, it may be appropriate to re-operate on the patient for further haemostasis. Conservative management may be indicated in smaller haemorrhages, but close monitoring should always be undertaken.

Specialist Areas

Neck Surgery

Post-operative thyroidectomy or parathyroidectomy haemorrhage can have catastrophic consequences and the operating surgeon must take great care to ligate any vessels and coagulate bleeding points.

The primary sign of post-operative haemorrhage is likely to be airway obstruction. This is because the pretracheal fascia of the neck will only distend so far; when bleeding occurs into this space, compression on the venous return results in venous congestion, with subsequent laryngeal oedema leading to eventual asphyxiation.

Any evidence of respiratory distress or airway compromise in these patients requires an emergency protocol for airway rescue. This involves removing both the skin clips and deep layer sutures, and suction of the haematoma beneath, all done at the bedside as there is no time to get the patient to theatre!

Urgent senior surgical opinion should be sought and an anaesthetic review should be organised. Eventually these patients require a return to theatre for a formal relook procedure.

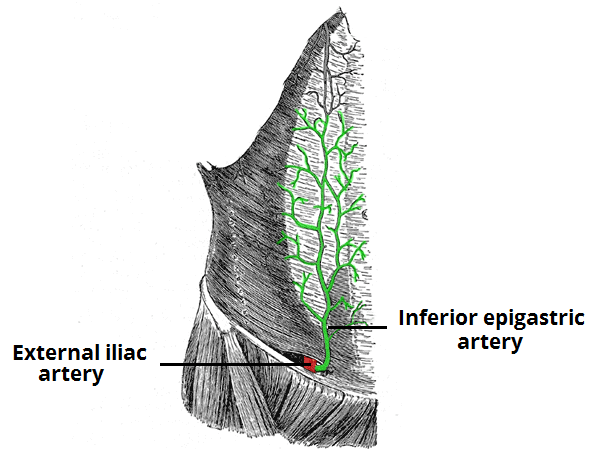

Inferior Epigastric Artery Injury

The inferior epigastric artery arises from the external iliac artery and runs up the abdominal wall below the rectus muscle, vertically in approximately the mid-clavicular line (Fig. 1). It is therefore vulnerable to injury from laparoscopic ports.

Due to the gas insufflation, this may not be noticed at the time of surgery. Always think of post-operative bleeding and inferior epigastric artery injury in an acutely unwell patient shortly after any surgery, but particularly after laparoscopic surgery or surgery with a Pfannenstiel incision.

Retroperitoneal Bleeding Post-Angiography

Many procedures are now performed using angiography, with an entry site in the groin. The puncture site is often the external iliac artery, above the inguinal ligament. Therefore, any bleeding from this artery can track into the retroperitoneum.

There will likely not be a large haematoma around the skin puncture site, because the actual arterial puncture site is hidden by the inguinal ligament. These patients often also bleed profusely because tamponading the injury is difficult.

For any suspected occult retroperitoneal haemorrhage, apply pressure to the puncture site, resuscitate the patient, ensure blood products are made immediately available, and call for senior support. Cross-sectional imaging to confirm the diagnosis is often required.

Key Points

- Post-operative bleeding can occur up to 10 days after the operation

- Any suspected haemorrhage requires rapid resuscitation of the patient, especially adequate fluid given

- Place pressure on any site of bleeding and get senior input urgently

- There are certain surgical approaches that require a high threshold of suspicion for any post-operative bleeding