Introduction

Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis (inflammation of the testes is termed orchitis)

The condition has a bimodal age distribution, occurring most commonly in males aged 15-30yrs and then again in males >60yrs. The incidence in the UK is approximately 25 per 10,000 people.

Classically, these two conditions are thought to occur together (termed epididymo-orchitis), however most cases are solely epididymitis, whilst a sole orchitis is very rare and is mostly of viral origin

Pathophysiology

Epididymo-orchitis is usually caused by local extension of infection from the lower urinary tract (bladder and urethra), either via enteric (i.e. classic UTI) or non-enteric (i.e. sexually transmitted) organisms.

In males aged <35 years old, the most likely mechanism is sexual transmission, therefore the most common organisms* are N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.

*In males who practice anal intercourse, enteric organisms such as E. coli are also a common cause

In males aged >35 years old, an enteric organism from a urinary tract infection is the more likely mechanism of the disease**. Therefore, the most common pathogens are E. coli, Proteus spp., Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa.

**This is often secondary to a bladder outflow obstruction from prostatic enlargement, leading to retrograde ascent of the pathogen

Mumps Orchitis

Orchitis can occur as a common complication of a mumps viral infection, occurring in up to 40% of post-pubertal boys with mumps infection.

It presents as unilateral or bilateral orchitis, typically accompanied with a fever, around 4-8 days after the onset of mumps parotitis. The disease self-resolves within a week with supportive management, however mumps orchitis can lead to complications such as testicular atrophy and infertility.

If mumps is suspected, mumps IgM/IgG serology should be measured. Mumps is a notifiable disease in the UK, meaning that the local Health Protection Team must be informed if there is suspicion of mumps.

Risk Factors

The risk factors for epididymo-orchitis depend on the mechanism of disease (STI or UTI).

Risk factors for non-enteric causes include males who have sex with males (MSM), multiple sexual partners, or a known contact of gonorrhea.

Risk factors for enteric causes include recent instrumentation or catheterisation, bladder outlet obstruction (e.g. prostate enlargement, urethral stricture), or an immunocompromised state.

Clinical Features

Epididymitis usually presents as unilateral scrotal pain and associated swelling. Fever and rigors can also be present.

Associated symptoms (secondary to the underlying cause) may also be present, such as dysuria, storage LUTS, or urethral discharge. Ensure to clarify a sexual history in all cases.

On examination, the affected side will be red and swollen. The epididymis +/- the testis will be very tender on palpation, and there may be an associated hydrocele. The remainder of the cord structures usually be normal; bilateral epididymitis is very rare.

Specific tests include assessing for the cremasteric reflex, which is intact in cases of epididymitis, and Prehn’s sign, which when positive is also suggestive of epididymitis.

Prehn’s Sign

Prehn’s sign can be used to further assess for suspected cases of epididymitis. The patient is supine and the scrotum is elevated by the examiner. In cases where the pain is relieved by elevation (a positive Prehn’s sign), this is suggestive of epididymitis.

Unfortunately, Prehn’s sign is unreliable; whilst it has good sensitivity, it has relatively poor specificity, therefore is not used routinely in clinical practice.

Differential Diagnosis

Testicular torsion is the most important differential, as it is a surgical emergency. Pain is more sudden onset and severe, in the absence of LUTS. Whilst US Doppler can aid in the diagnosis, any significant suspicion of torsion should warrant urgent scrotal exploration.

Other differentials to consider in cases of suspected epididymitis include testicular trauma, testicular abscess, epididymal cyst, hydrocoele, or testicular tumour

Investigations

All suspected cases should have a urine dipstick performed (checking for evidence of infection), with a low-threshold for sending for urine culture (MC&S).

For suspected non-enteric epididymitis, first-void urine should be collected and sent for Nucleic Acid Amplification Test (NAAT), to assess for N. gonorrhoeae, C. trachomatis, and M. genitalium. Further STI screening may be warranted, dependent on the history.

Routine bloods, including FBC and CRP, can aid in the assessment for an infective cause. Any evidence of systemic infection may warrant blood cultures to also be collected.

Imaging

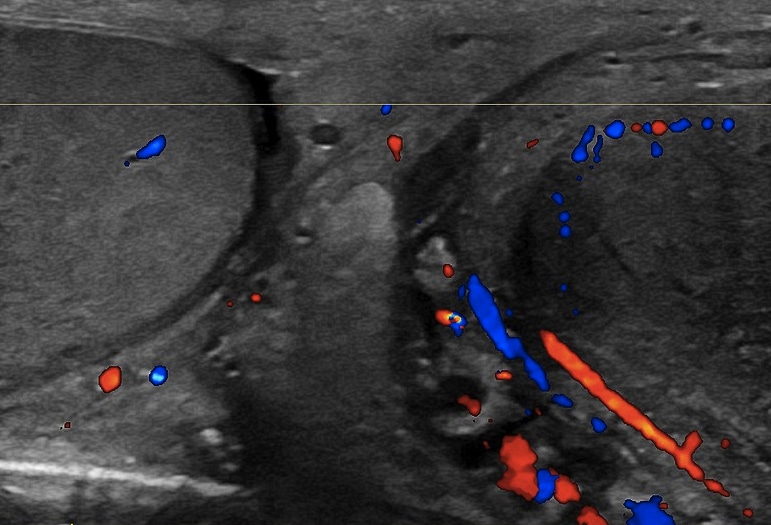

The diagnosis of epididymitis is typically a clinical one, however ultrasound imaging of the testes via an US Doppler can be useful to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 2)* and to rule out any complication (e.g. testicular abscess).

*A colour Doppler ultrasound scan will be able to show increased vascularity of the epididymis in suspected cases; whilst it can also be used to assess testicular blood flow, if there is suspicion of testicular torsion, the patient should be sent for scrotal exploration.

Management

Initial management

In the majority of cases, patients with epididymitis can be treated as an outpatient, unless evidence of systemic infection, uncontrolled pain, or warranting further investigation.

Patients should be started on appropriate antibiotic therapy and provided with sufficient analgesia. Bed rest and scrotal support will also help in symptomatic improvement.

Antibiotic therapy forms the mainstay of treatment, where the antibiotic regimen depends on the suspected cause, and can be started empirically prior to any culture results.

Current EAU Guidelines suggest first line treatments* of:

- Enteric organisms – Ofloxacin 200mg PO BD for 14 days or levofloxacin 500mg BD for 10 days

- Sexually-transmited organisms – Ceftriaxone 500mg IM single dose and Doxycycline 100mg PO twice daily for 10-14 days (with Azithromycin 1g PO single dose added if gonorrhoea likely)

*For cases that do not improve with initial therapy, discussions with microbiology and investigation potential underlying causes are advised

Patients should abstain from sexual activity until the antibiotic course is completed and symptoms resolve. Patients should also be counselled on appropriate barrier contraception use to reduce risk of sexually transmitted infections.

Routine follow-up of these patients is not typically recommended; however, the patient should seek further assessment if symptoms do not resolve or deteriorate. For cases of chronic epididymitis that prove to be refractory to all other therapy and have a persistent pain, orchiectomy may be warranted in rare cases.

Complications

Typically, symptoms improve within 48hours of starting antibiotics. Complications of epididymitis can include reactive hydrocele formation, abscess formation (rare), or testicular infarction (rare).

Key Points

- Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis, most common in those aged 15-30yrs and again >60yrs

- Cases usually presents as unilateral scrotal pain and associated swelling; bilateral epididymitis is rare

- Diagnosis is clinical, however can be aided by ultrasound Doppler imaging

- Antibiotic therapy and analgesia are the mainstay of management