Introduction

Pyrexia (fever) refers to a raised body temperature, typically greater than 37.5c. It is common in surgical patients, either normal immediate post-operative response or as feature of a specific post-operative complication.

Whilst infection is regularly the suspected cause, other conditions must be considered when approaching the surgical patient with pyrexia (Fig. 1).

In this article, we shall look at the aetiology, investigations and management of pyrexia in the post-operative surgical patient.

Aetiology

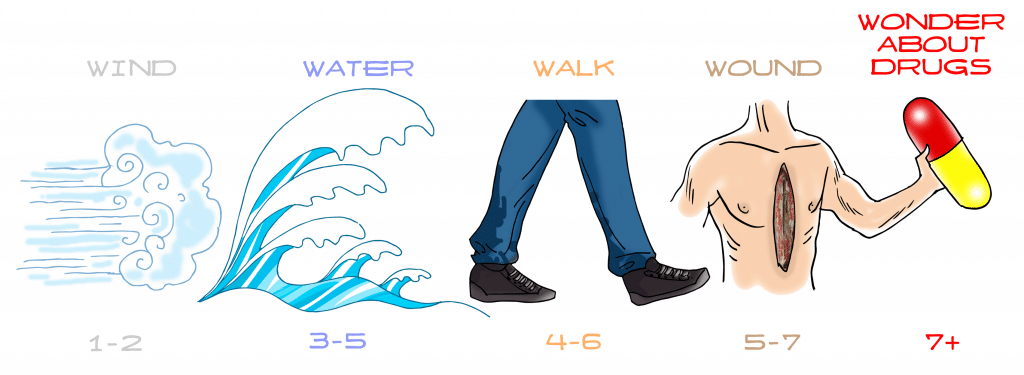

The most common cause of pyrexia in the post-operative patient is infection. The specific post-operative day on which the fever develops may indicate the source of the infection:

- Day 1-2 – consider a respiratory source (or body’s routine response to surgery)

- Day 3-5 – consider a respiratory or urinary tract source

- Day 5-7 – consider a surgical site infection or abscess/collection formation

- Any day post-operatively – consider infected IV lines or central lines as a source

The investigation of the infection source should also be tailored to the patient. For example, in a patient who has undergone a bowel resection and anastomosis, anastomotic leak is an important differential to be considered and should be investigated as a matter of urgency.

Other Causes of Pyrexia

Other causes of post-operative pyrexia include:

- Iatrogenic – which may include a drug-induced reaction (e.g. antibiotics or anaesthetic agents) or from a transfusion reaction

- Venous thromboembolism – although rare, a PE or DVT can cause a low grade fever without any other overt clinical features

- Secondary to prosthetic implantation – with any foreign body, for example after an AAA repair, a low-grade fever may be evident

- Pyrexia of Unknown Origin

Pyrexia of Unknown Origin

Pyrexia of Unknown Origin (PUO) is defined as a recurrent fever (>38oc) persisting for >3wks without an obvious cause, despite > 1 week of inpatient investigation.

Causes of PUO include infection of unknown source (30%), malignancy (classically B-symptoms from lymphoma, 30%), connective tissue diseases or vasculitis (30%), or drug reactions.

Clinical Features

The underlying source of the pyrexia will largely determine the clinical presentation of the patient. Importantly, if the patient appears unwell and needs urgent resuscitation and management, start an A to E approach as necessary and only attempt to identify the source of infection once the patient is stable.

If no obvious source is apparent, enquire about specific systems symptoms, such as urinary frequency, urgency, or dysuria, productive cough or dyspnoea, haemoptysis, chest or calf pain, or wound or cannula line tenderness.

On initial examination, examine for signs of respiratory infection, intravenous line infections, wound infections, and calf tenderness. If post-operative, examine for specific complications from the operation (e.g. signs of peritonism in an anastomotic leak).

Investigations

A septic screen is essential in investigating the surgical patient with pyrexia. In most cases, the source is obvious and your screen can be tailored accordingly, yet in a less clear presentation a wider screen is indicated; this can include:

- Blood tests – FBC, CRP, U&Es, LFTs, clotting

- Urine dipstick +/- urine MCS

- Cultures – blood, urine, sputum, and wound swab

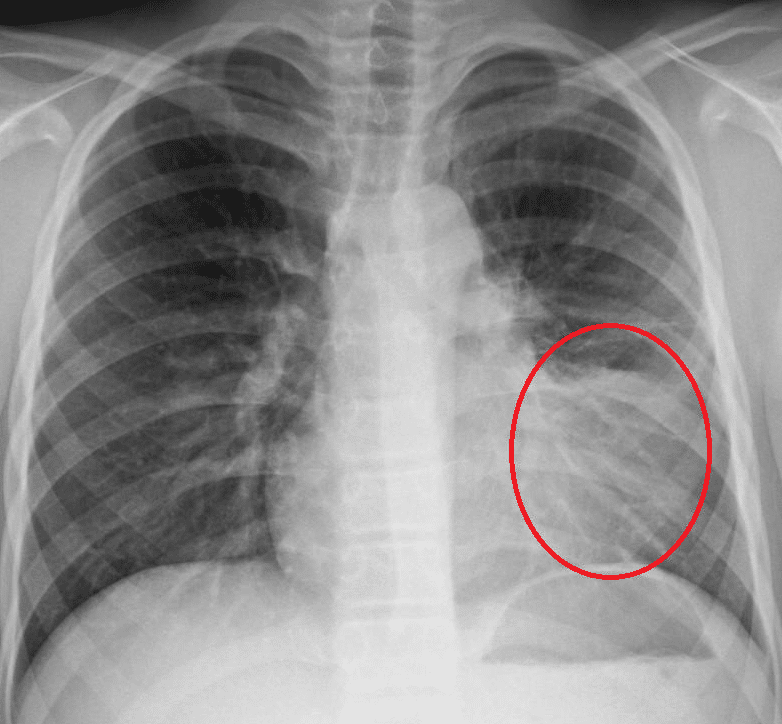

- Imaging – Plain film chest radiograph, specific cross-sectional imaging

If the source cannot be identified through the septic screen, more detailed investigations may be required

Management

Any identified infection should be treated empirically with antibiotics, pending sensitivity results from any cultures taken. Empirical antibiotic regimes will vary depending on local sensitivities and patient allergies, therefore following local hospital guidance is advised.

If no infectious cause can be identified, starting empirical antibiotics straight away is not always essential. First look for non-infectious causes and consult a senior colleague and a microbiologist for further advice.

A low threshold of suspicion should be present for suspected sepsis and any concerns should warrant an early senior review.

Key Points

- Ensure to take an A to E approach for all cases of pyrexia in the surgical patient

- Consider the time since operation and details of the procedure to help focus your investigations

- Not all cases of pyrexia are due to infection