Introduction

Renal transplantation (RT) is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD). It has significant benefits to quality of life and patient survival as well as a significant economic benefit when compared to dialysis.

Kidneys can be donated from either living donors or deceased donors, with the majority of renal transplants from deceased donors in the UK. Deceased donors are either Donation after Brainstem Death (DBD) or Donation after Circulatory Death (DCD).

Living-donor transplants account for up to 30% of all kidney transplantations, either related or unrelated, performed as a laparoscopic donor nephrectomy (rarely this is done as an open nephrectomy in modern practice).

One year survival for deceased transplant recipients is 96% and for living donor transplant recipients is 99%.

Indications

All patients with end stage renal failure (GFR<15ml/min or requiring permanent dialysis) should be assessed for renal transplantation. Those expected to require dialysis within 6 months should be worked-up pre-emptively but may not be activated on the waiting list until they meet the above criteria.

Contraindications, both absolute and relative, to kidney transplantation are shown in Table 1.

| Absolute | Relative |

| Untreated malignancy

Active infection Untreated HIV infection or AIDS Any condition with a life expectancy <2 years |

Predicted patient survival of <5 years or predicted risk of 1-year graft survival <50%

Malignant disease not amenable to curative treatment, or remission for >5 years* HIV infection not treated with anti-retroviral therapy or already progressed to AIDS Cardiovascular disease, ischaemic heart disease which cannot be revascularised for prognostic benefit or heart failure with ≥50% risk death within 5-years. Patients who are unlikely to adhere to immunosuppressive therapy Immunosuppression predicted to cause life-threatening complications |

Table 1 – Contraindications to renal transplantation *excluding non-melanoma skin cancer.

Surgical Techniques

Donor Retrieval Procedure

Organs are retrieved in a similar fashion using cold perfusion during both DBD and DCD retrievals. In DBD retrievals, there is also a period of dissection which allows assessment of the organs during the procurement process and minimises warm ischaemia. During DCD retrieval, a rapid cannulation of the systemic circulation and delivery of cold perfusion fluid is performed to limit the exposure of the organs to warm ischaemia. Perfusion fluid and heparin help to prevent micro-thromboses within the organs.

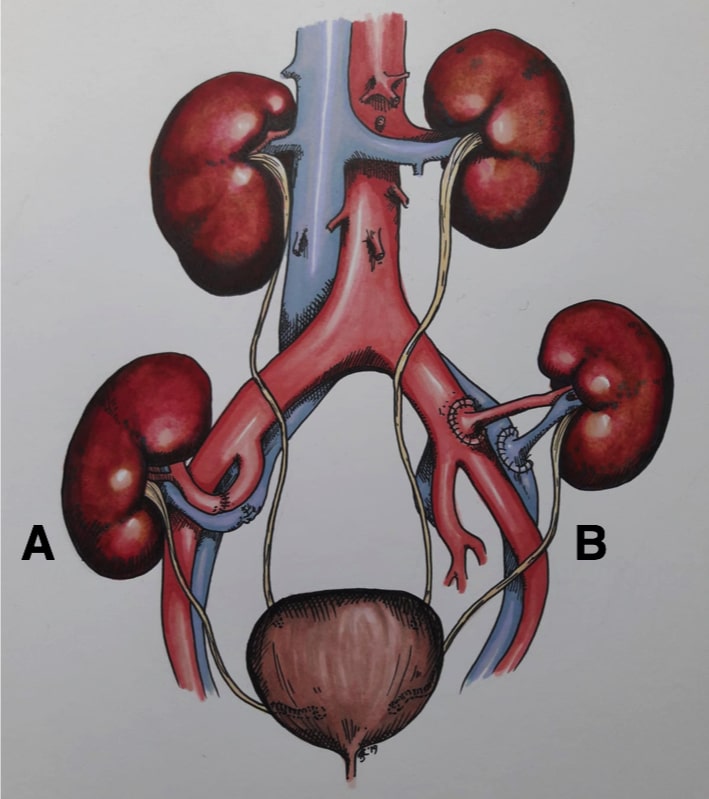

Full exposure of the abdomen is obtained and the bowel is mobilised to access to the retroperitoneal space. The vessels and ureter(s) are identified and isolated. The kidneys are then removed with the renal artery and a patch of aorta, the renal vein with a patch of the IVC, and the ureter. The organs are then taken to the back table for further examination and perfusion.

For living donor kidney transplantation, the nephrectomy is most commonly performed via a laparoscopic or hand-assisted technique. The left kidney is preferred because of a longer renal vein, however no patch of aorta or IVC can be taken in these cases. Again, the kidney, once removed, should be flushed with preservation fluid as soon as possible. The mortality of donor nephrectomy is low, estimated at 1 in 3000 for all surgical approaches.

Warm Versus Cold Ischaemia Time

Warm ischaemia time (WIT) is the time between the cessation of organ perfusion by the donor’s blood circulation (i.e. for living donors this is at the point of ligation of the renal artery, whilst for DCD donors this is at the point of cardiac arrest) until perfusion with preservation solution. In DBD donors, cold perfusion begins before cardiac arrest so there is no warm ischaemia time. A further period of warm ischaemia occurs in all transplants when the kidney is removed from ice for implantation until reperfusion in the recipient.

Cold ischaemia time (CIT) is the time from the perfusion of the organ with the preservation solution to re-perfusion of the organ with recipient blood after the implant’s vascular anastomosis. Warm ischaemia is significantly more damaging to tissues than cold ischaemia. However, both should be minimised to avoid organ damage and impaired graft function.

Recipient Procedures

If transported from another centre, the kidney will arrive stored in perfusion fluid (within sterile bags) and surrounded by ice. The kidney should be benched and examined, the renal artery and vein identified and prepared, flushed with preservation solution (to check for leaks), and any leaks repaired, with the ureter length fully preserved and any additional surrounding fat removed.

The graft is commonly placed extraperitoneally in the iliac fossa, most commonly the right side. Dissecting retroperitoneally in the iliac fossa, the iliac vessels are exposed and any lymphatics identified are ligated. Anastomoses are usually performed end-to-side between donor renal vein and recipient external iliac vein, and between donor renal artery and recipient internal or external iliac artery.

The kidney is reperfused and the ureter is anastomosed to the bladder through the formation of an ureteroneocystostomy. The anastomosis is often performed over a ureteric stent which can be removed cystoscopically around 4-6 weeks after the transplant.

Complications of Renal Transplant

Delayed Graft Function

Delayed graft function (DGF) is defined by the need for dialysis in the first week after transplantation. Its risk increases with prolonged WITs and CITs (therefore is relatively rare with living donor grafts). Whilst most DGF kidneys eventually function, there is a recognised association with increased rejection rates and decreased graft survival rates. Transplanted kidneys which never work, termed primary non-function (PNF), are rare (~1%)

Organ Rejection

Organ rejection is immunological damage of the transplanted kidney from the recipient’s immune system. This can be T-cell or antibody mediated and occurs in approximately 10-15% of kidney recipients within the first year. It is avoided by matching organs to recipients through blood group and HLA matching prior to transplant and immunosuppression which is required for the duration of the life of the transplant. Most rejection is treatable if detected early and hence renal function is monitored regularly during follow-up.

Vascular Complications

Vascular complications are divided in early and late.

Early complications comprise renal artery thrombosis (rare, 1%) and renal vein thrombosis (6%). They must be recognised promptly using a Doppler ultrasound and will require taking back to theatre urgently if identified. Aspirin and/or heparin are often started post-operatively to reduce this risk

Late complications include renal artery stenosis, which usually presents several months post transplantation with uncontrollable hypertension and worsening graft function. Angiography confirms the diagnosis and the treatment of choice is typically angioplasty.

Figure 2 – Angiogram following angioplasty, in patient with renal artery stenosis (in a native kidney)

Ureteral Complications

Ureteric leaks occur from a breakdown of the ureteric-bladder anastomosis, presenting with a decreased urine output and increasing abdominal pain. They often require repeat surgical intervention.

Urinary tract obstruction can also occur, through ischaemic strictures in the distal ureter (treated with dilatation) or extrinsic compression from a lymphocele or haematoma (treated via drainage).

Long-term Complications

The most common cause of mortality post-operatively within the first year is cardiovascular disease.

Most other longer term complications are often related to the use of immunosuppressive agents, such as recurrent infections or viral reactivation (e.g. CMV), diabetes mellitus, or malignancy.

Key Points

- Renal transplantation is the treatment of choice for patients with end-stage renal disease

- Several complications can occur post-operatively, including delayed graft function, vascular complications, and ureteric complications

- One year survival for deceased donor transplant recipients is around 96% and for living donor transplant recipients is around 99%