Introduction

Bone tumours can be divided into primary and secondary (metastatic) tumours. Primary tumours arise from cells which constitute the bone and can divided into benign and malignant types (Table 1).

|

Tissue Type |

Benign |

Malignant |

| Bone forming | Osteoma

Osteoid osteoma Osteoblastoma |

Osteosarcoma |

| Cartilage forming | Chondroma

Osteochondroma Chondroblastoma |

Chondrosarcoma |

| Fibrous tissue | Fibroma

Fibromatosis |

Fibrosarcoma |

| Giant-cell tumours | Benign osteoclastoma | Malignant osteoclastoma |

| Marrow tumours | Ewing’s tumour

Myeloma |

Table 1 – List of bone tumours, divided into benign and metastatic

Metastatic bone tumours make the most of the disease burden. Primary bone tumours are relatively rare, with an overall prevalence of less than 1% in the UK. In children & adolescents, bone cancer is more common, comprising around 5% of all cancers.

Metastatic Bone Cancer

Metastatic spread from other cancer types is the most common cause of bone cancer, the most common primary sites being renal, thyroid, lung, prostate, and breast. The most common site for a bony metastases is the spine.

Metastatic disease is rarely treated surgically, with the mainstay of disease management via systemic therapies and often are palliative. Prophylactic nailing of certain long bones can be performed in certain individuals at high risk of pathological fractures from metastatic disease, especially of the femur and humerus.

Risk Factors

There are certain well documented risk factors for developing a primary bone cancer:

- Genetic association

- RB1(familial retinoblastoma) and p53 (Li Fraumeni syndrome) are associated with an increased risk of osteosarcomas

- Mutations to TSC1 andTSC2 mutation (tuberous sclerosis) are associated with an increased risk of chordomas during childhood

- Previous exposure to radiation or alkylating agents in chemotherapy

- Benign bone conditions, such as Paget’s disease and fibrous dysplasia (both increase the risk of osteosarcoma)

Clinical Features

The main symptom of a (primary) bone tumour is pain. This is typically not associated with movement and is worse at night (often deemed a ‘red flag’ symptom).

As the tumour enlarges, a mass may be palpable. If the patient presents with a fracture without a history of trauma (pathological fracture), a bone tumour may be suspected.

Differential Diagnosis

Patient presenting with ongoing bone pain can have a wide variety of conditions, including osteomyelitis, multiple myeloma, metabolic bone disease (e.g. renal osteodystrophy), or a pathological fracture.

Bone Tumours

Primary bone tumours can be either benign or malignant; here, we discuss the most common types of primary bone tumours.

Benign

Osteoid Osteoma

Osteoid osteomas arise from osteoblasts, often around the second decade of life (10-20yrs), and are more common in males. They are typically small tumours (<2cm), located usually around the metaphysis of long bones (e.g. proximal femur or tibia).

They present with a localised progressive pain, worse at night, and typically made better with NSAIDS. There may be associated localised swelling, tenderness, or limping.

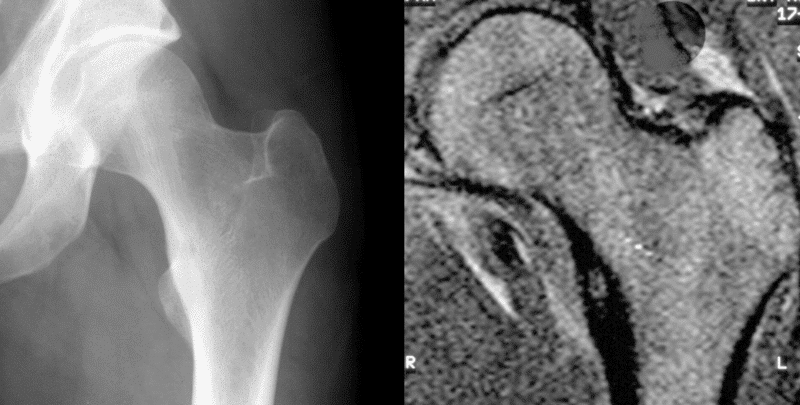

Radiologically they show a small mass, comprised of a radiolucent nidus with a rim of reactive bone (Fig. 2). Most can be managed conservatively through serial radiological imaging every 4-6 months, however those with severe pain may warrant surgical resection. Overall they have a good prognosis, with most resolving spontaneously.

Figure 2 – Osteoid osteoma at the lesser trochanter, on plain film radiograph and subsequent MRI scan

Osteochondroma

Osteochondromas (also known as exostoses) are benign bony tumours*, forming as an outgrowth from the metaphysis of long bones covered with a cartilaginous cap. They develop most commonly in the second decade of life (10-20yrs) and are more common in males.

Most are detected incidentally, as usually are asymptomatic and slow growing, although can cause deformities or impinge on nerves if they grow large enough. On plain film radiograph, they show as a pedunculated bony outgrowth from metaphysis pointing away from the joint (Fig. 3).

Most can be managed conservatively through serial radiological imaging every 4-6 months, however those with significant deformity or neurological symptoms may warrant surgical resection.

*85% occur as solitary osteochondromas, however osteochondromas are also associated with hereditary conditions, such as Multiple Hereditary Exostoses (MHE) Syndrome.

Figure 3 – Multiple osteochondromas as seen on plain film radiograph affecting the left knee

Chondroma

Chondromas arise* from chondroblasts within the medullary cavity of the bones (termed enchondromas) or from the cortical surface. They present in patients 20-50 years old, most commonly affecting the long bones of the hands, femur, and humerus.

Most of asymptomatic, however they can present as a pathological fracture. On plain film radiograph, they appear as a well circumscribed oval lucency with intact cortex.

Chondromas should be managed depending upon the size and clinical features. Most asymptomatic and small chondromas can be observed, however large or symptomatic chondromas may require removal with curettage and bone grafting. There is a small risk of transformation into chondrosarcomas (malignant).

*Two syndromes are associated with chondromas, Ollier’s disease and Maffucci syndrome, both of which are characterised by the formation of multiple enchondromas

Giant Cell Tumour

Giant cell tumours, also called osteoclastomas, arise from the multinucleated giant cells and stromal cells. They occur in patients 20-30 years old, usually affecting the epiphysis of long bones (most commonly the distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal radius).

Patients will typically present with pain, swelling, or a limitation of joint movement. On plain film radiograph, giant cell tumours show an eccentric lytic area, giving a “soap bubble” appearance.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice, potentially requiring bone grafting or reconstruction.

Malignant

Osteosarcoma

Osteosarcomas are the most common malignant primary bone tumour*. They have a bimodal age of onset, either in paediatric cases (mainly 10-14 years) or in those aged >65yrs (typically in those with Paget’s disease), and most commonly found at the metaphysis of the distal femur or proximal tibia.

Patients present with localised constant pain and a tender soft tissue mass may be palpable. Plain film radiographs will show medullary and cortical bone destruction, with significant periosteal reactions (termed “Codman’s triangle” or as a “sunburst pattern”).

Tissue biopsy is required for diagnosis and typically warrants aggressive surgical resection with systemic chemotherapy. Osteosarcoma are predisposed to metastasise to the lung and bone.

*Genetic conditions with a known predisposition to osteosarcoma include hereditary retinoblastoma and Li-Fraumeni syndrome.

Ewing’s Sarcoma

Ewing’s sarcomas are paediatric malignancies, more common in males, and arise from primitive poorly differentiated neuroectodermal cells. They commonly affect the diaphysis of long bones.

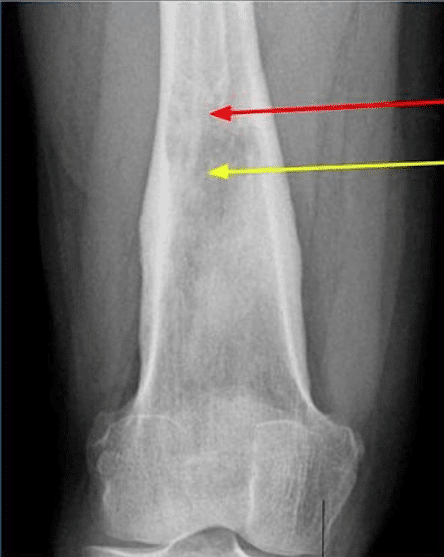

Patients present with a painful and enlarging mass with tenderness and warmth (often initially mistaken as osteomyelitis). Plain film radiographs demonstrate lytic lesion with periosteal reactions (Fig. 4), producing layers of reactive bone leading to characteristic “onion skin” appearance.

Management is via neoadjuvant chemotherapy followed by surgical excision. Radiation may be considered for local control in patients with unresectable primary tumours.

Figure 4 – Ewing Sarcoma affecting a tibia

Chondrosarcoma

Chondrosarcomas are malignant tumours of the cartilage, commonly arising as primary lesions but can appear as malignant transformation from benign chondromas (especially those with Ollier’s or Maffucci syndrome). For primary chondrosarcomas, the age of onset is 40-60 years, typically affecting the axial skeleton (especially the pelvis, shoulder, and ribs).

Patients typically present with a painful and enlarging mass. Plain film radiographs demonstrate lytic lesions with calcification, cortical remodelling, and endosteal scalloping (Fig. 5).

Low grade lesions can be treated using intralesional curettage, whilst wide en-bloc local excision is the preferred for intermediate- and high-grade lesions. Prognosis depends on the grade and location; axial skeleton and high grade tumours have a worse prognosis.

Investigations

Investigations for a suspected bone tumour vary depending on suspected tumour type. Most will obtain initial plain film radiographs, however all suspected cases should be discussed in an appropriate multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting before further investigations are arranged.

Most suspected cases will need MRI imaging to assess the lesion, as well as evidence for soft tissue involvement. CT imaging can be useful in determining cortical involvement. In certain cases, a bone biopsy may be required for definitive diagnosis.

Radiological Features of Bone Tumours

Features from a plain film radiographs can help in determining whether a suspected bone tumour is either benign or malignant:

- Benign lesions are often sharp and well-defined, lacking soft tissue involvement and no cortical destruction

- Malignant lesions are often poorly defined with rough borders, involving soft tissues and have cortical destruction

If there is any degree of suspicion or uncertainty, additional imaging for further assessment should be sought.

Enneking Staging System

The Enneking staging system is the most commonly used staging system for orthopaedic tumours. It comprises of two components, for both benign and malignant tumours respectively

For benign tumours, staging is based on radiographic characteristics of the tumour margin. It consists of three categories:

- Latent – Have well-demarcated borders that grow slowly, can heal spontaneously (osteoid osteoma), and have negligible recurrence after intracapsular resection

- Active – Well defined borders but may show cortical thinning, their growth is often limited by natural barriers, and there is negligible recurrence after marginal resection

- Aggressive – Have indistinct borders and their growth is not limited by natural barriers, have high recurrence rates after intracapsular or marginal resection (therefore a wide resection margin is preferred)

For malignant tumours the staging is based on the surgical grade (G, G1, G2), the local extent (T, T1, T2), and the presence or absence of metastasis (M0, M1). These are then divided into 3 separate stages, and further subdivided into two subcategories (A, B) based on the local extent of the tumour:

| Stage | Grade | Site | Metastasis |

| IA | Low (G1) | Intracompartmental (T1) | No metastasis (M0) |

| IB | Low (G1) | Extracompartmental (T2) | No metastasis (M0) |

| IIA | High (G2) | Intracompartmental (T1) | No metastasis (M0) |

| IIB | High (G2) | Extracompartmental (T2) | No metastasis (M0) |

| III | Any (G) | Any (T) | Regional or distant metastasis (M1) |

Table 2 – Enneking Staging System for Malignant Bone Tumours

Management

Management of bone tumours depends on patient factors and disease factors. However, in general most benign bone tumours are managed with observation, whilst surgical treatment is the mainstay for malignant tumours.

Key Points

- Bone tumours can be divided into primary and secondary (metastatic) tumours; primary tumours can divided into benign and malignant types

- Secondary tumours are the most common type of bone tumour

- The mainstay of initial investigation is via MDT discussion, before further imaging is undertaken

- Most benign bone tumours are managed with observation, whilst surgical treatment is the mainstay for malignant tumours