Introduction

Deep neck space infections (DNSIs) are serious ENT presentations, with the potential for the patient to rapidly deteriorate with airway compromise. Mortality rate is between 1% to 2%.

The infection will typically spread from the oropharyngeal region and into the fascial planes (see below). The main types of DNSI are:

- Parapharyngeal abscess – forms when infection spreads to the potential space posterolateral to the nasopharynx (most common subtype)

- Retropharyngeal abscess – infection spreads to the potential space anterior to the prevertebral fascia (commonly seen from necrotising lymph nodes in children)

- Submandibular space abscess – most commonly due to spread of dental infection into the potential submandibular, submental, or sublingual spaces (also termed Ludwig’s angina); infection within sublingual spaces causes gross tongue swelling which can lead to rapid airway obstruction.

DNSIs are usually polymicrobial, given their usual source from the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. Streptococcus viridans is the most common culprit, with Staphylococcus, anaerobes, and Gram-negative bacilli are also commonly causative pathogens.

Anatomy

The cervical fascia can be divided anatomically into superficial and deep fascia. The superficial fascia consists of skin, subcutaneous tissue and the platysma, whilst the deep fascia is further divided into superficial, middle and deep layers.

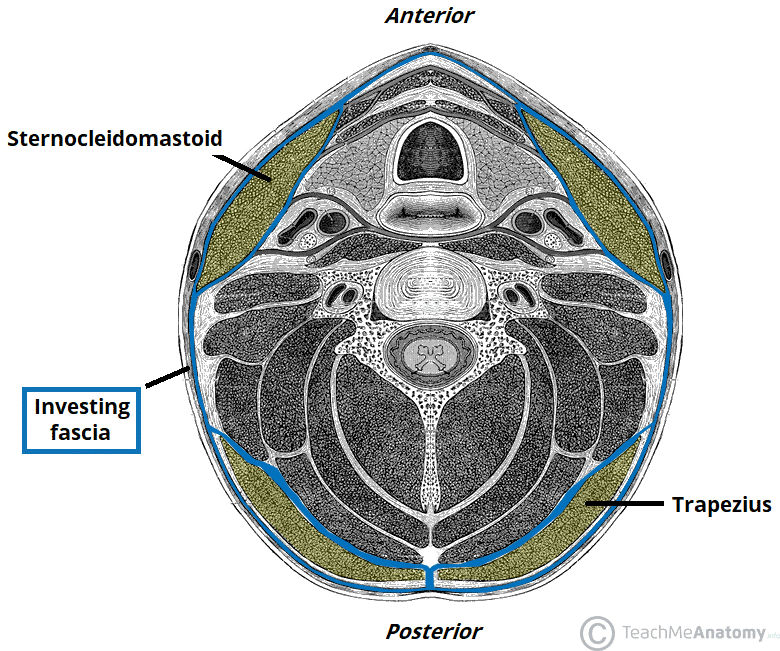

The superficial layer (or investing layer) of the deep fascia covers the submaxillary and parotid glands as well as muscles deep to the platysma (the trapezius, sternocleidomastoid and strap muscles). This layer encloses the submandibular and masticator spaces, which can be a focus of dental or submandibular infections (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 – Transverse section of the neck, with the investing layer of fascia highlighted in blue

The middle layer (or pretracheal layer) encloses the visceral organs of the neck, namely (from anterior to posterior), the thyroid and parathyroid glands, the larynx and trachea, the pharynx, and oesophagus.

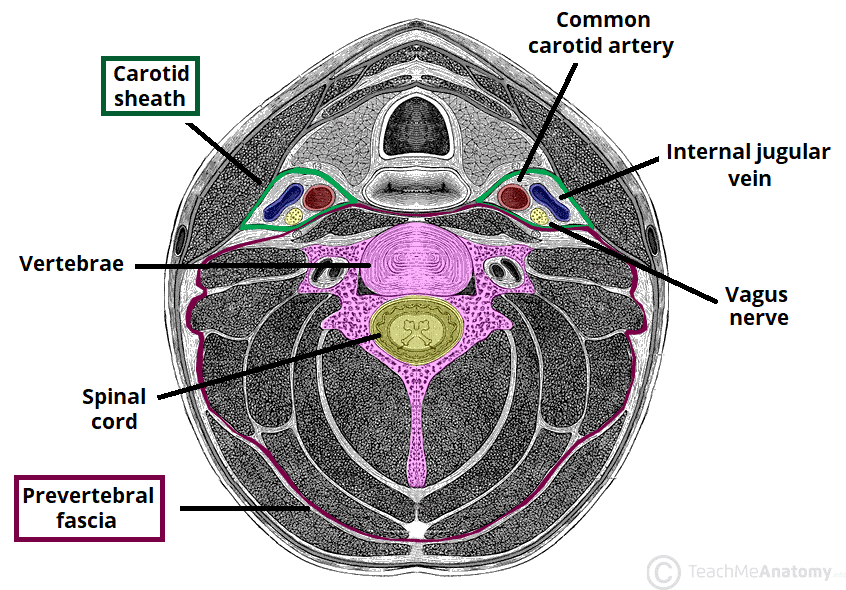

The deep layer (or prevertebral layer) covers the vertebral column and the paravertebral muscles (Fig. 2). There is a potential space between the middle and deep layers anteriorly, termed the retropharyngeal space, which is subdivided by a thin membrane called the alar fascia. Posterior to the retropharyngeal space is the “danger space”, which extends from the oropharyngeal region inferiorly into the posterior mediastinum to the level of the diaphragm.

The parapharyngeal space is a potential space on bilateral aspects of the neck, which is shaped like an inverted cone, bordered superiorly by the skull base and inferiorly by the hyoid bone. Medially it is bordered by the pretracheal fascia, and laterally by the superficial fascia. It is divided into anterior and posterior compartments by the styloid process and its attached muscles.

Clinical Features

Patients can present with a wide range of symptoms*, including severe sore throat, difficulty breathing, new-onset dysphagia or odynophagia, drooling, voice changes (such as hoarseness or voice loss), or neck stiffness.

On examination, the patient will look unwell with systemic signs of infection, including pyrexia. Clinical signs of DNSI include stridor, trismus, pharyngeal swelling (these can often be discrete), and cervical lymphadenopathy. Local signs of erythema, oedema or fluctuance may be absent, therefore a low threshold of suspicion is required.

Ensure to assess for any peritonsillar abscess, dental infections, and the openings of the salivary glands orally. Examine for any suppurative parotitis. This is because these are the commonest sources of infection that can contribute to deep neck space abscesses.

*In children, this may only present with drooling, agitation, or being off feeds

Red Flags for Deep Neck Space Infection

There are important red flags to be aware of in suspected DNSI patients, as these patients can quickly decompensate and need urgent management; if any of these are suspected, urgent senior involvement is required:

- Sore throat in the absence of an abnormal oropharyngeal examination

- Severe neck pain or stiffness

- Any signs of airway compromise, such as stridor, dyspnoea, drooling, dysphonia

A fibreoptic nasal endoscopy is an important adjunct to the examination, as this can assess the patency of the airway and the supraglottic structures. In a DNSI, these structures are usually inflamed and oedematous, so be aware of causing further distress to the patient when performing this examination.

Apart from supraglottic structures, it is also important to look at the pharyngeal wall to identify any parapharyngeal swelling. Any swelling or asymmetry in the pharyngeal wall should trigger concerns regarding DNSI.

Differential Diagnosis

DNSIs arise from heterogeneous causes, so there are broad differentials to patients presenting with some, or all of the features of DNSIs. These include foreign bodies, tonsillitis or peritonsillar abscess, Ludwig’s angina, epiglottitis, or meningitis or encephalitis

Investigations

Initial bloods will show raised inflammatory markers (often extremely high), with potential signs of end-organ dysfunction if the patient is septic. Blood cultures should also be taken in suspected cases.

The mainstay of investigation is a CT neck with intravenous contrast (Fig. 3), which will identify the location and extent of the infection, and should be performed urgently in any suspected cases.

Plain film lateral view neck radiographs can show widening of retropharyngeal tissue (>7mm at C2, >22mm at C7), however lack sensitivity and specificity to warrant any routine use for investigation in modern practice.

Management

Patients should be started on broad-spectrum antibiotics, as per local guidelines, with sufficient aerobic and anaerobic cover based on the polymicrobial nature of DNSIs. Intravenous dexamethasone can be given to aid reduce any airway sweeling

Ensure adequate fluid resuscitation and provide humidified oxygen with saline nebulisers (adrenaline nebulisers can also be trialled); a low threshold for intubation should be had if any signs of airway compromise are present. Ensure early senior support and keep the patient nursed at 45 degrees (at least) where possible.

Surgical Management

The mainstay of management is through surgical drainage (or sometimes radiological-guided) and washout of the DNSI. Drainage can be done through the mouth or through the neck, depending on the type of abscess, and drains will need to be left in.

Occasionally, the DNSI may have spread inferiorly to the mediastinum, so cardiothoracic involvement may be warranted.

Post-operatively, patients should be carefully observed for clinical and biochemical improvement. Occasionally, DNSIs may re-accumulate and spread, so re-exploration and repeat washout of the infection may have to be conducted several times.

Key Points

- Deep neck space infections are serious ENT presentations and have the potential to cause rapid deterioration with airway compromise

- Any suspected cases require urgent broad spectrum antibiotics

- Mainstay of imaging is with CT neck with intravenous contrast

- Nearly all cases will require surgical drainage, and close observation in the post-operative period