Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is the most common form of inflammatory bowel disease, alongside Crohn’s disease (CD). It develops mainly through a combination of genetic predisposition and environmental exposures.

There are approximately 5 million cases of ulcerative colitis around the world and incidence is increasing. The peak age of onset is between those aged 15-40yrs old, however incident cases in people >60yrs are increasing (accounting up to 20% of new diagnoses). Males and females are affected equally.

The disease typically follows a remitting and relapsing course. A severe fulminant exacerbation may be life-threatening, resulting in severe systemic upset, toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, and even mortality.

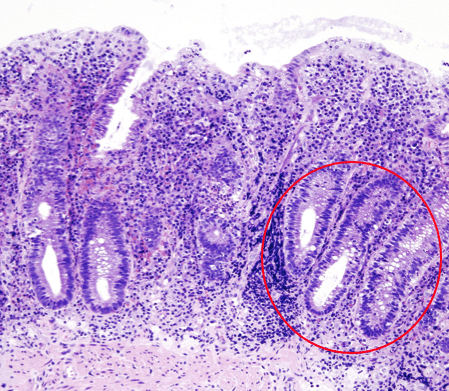

Figure 1 – Histology in ulcerative colitis, with non-granulomatous inflammation & crypt abscess formation

Pathophysiology

The pathogenesis of ulcerative colitis is complex and its aetiology remains incompletely understood. Current views suggest that it occurs after environmental exposures in individuals with a genetic predisposition, with epithelial barrier defects, dysregulated immune responses, and dysbiosis being key in initiating and perpetuating inflammation.

It is characterised by diffuse continual mucosal inflammation of the large bowel, beginning in the rectum and spreading proximally. This can potentially affect the entire large bowel, with up to 20% cases also having terminal ileal involvement, termed “backwash ileitis”.

Histological changes include non-granulomatous inflammation of the mucosa and submucosa, crypt abscesses (Fig. 1), and goblet cell hypoplasia (Table 1). Repeated cycles of ulceration and healing may lead to raised areas of inflamed tissue termed “pseudopolyps”.

Much like Crohn’s disease, it appears to have a familial link.

| Ulcerative Colitis | Crohn’s Disease | |

| Site Involvement | Large bowel | Entire gastrointestinal tract |

| Inflammation | Mucosal involvement only | Transmural involvement |

| Microscopic Changes | Crypt abscess formation Reduced goblet cells Non-granulomatous |

Granulomatous (non-caseating) |

| Macroscopic Changes | Continuous inflammation (proximal from rectum) Pseudopolyps and ulceration |

Discontinuous inflammation (‘skip lesions’) Fissures and deep ulcers (‘cobblestone appearance’) Fistula formation |

Table 1 – Characteristic Features of Inflammatory Bowel Disease

Clinical Features

The most common manifestation of ulcerative colitis is proctitis, with inflammation confined to the rectum only. As such, the cardinal feature of ulcerative colitis is bloody diarrhoea, with visible blood in stool reported in more than 90% of cases.

Symptoms are often present for several weeks before medical advice is sought. Other symptoms of UC include mucus discharge per rectum, increased stool frequency and urgency, and tenesmus.

Patients presenting with more widespread colonic involvement may develop clinical features of dehydration or systemic symptoms such as malaise, anorexia, or low-grade pyrexia.

In patients with an acute severe flare of ulcerative colitis, or particularly with toxic megacolon or colonic perforation, patients will complain of severe abdominal pain. On examination, such patients will be systemically unwell with signs of peritonism.

Disease Grading

The severity of an Ulcerative Colitis exacerbation can be graded using the Truelove and Witt criteria (Table 2). The severity degree is based on the presence of any one of the criteria:

| Criteria | Mild | Moderate | Severe |

| Bowel movements per day | <4 | 4-6 | >6 |

| Blood in stool | Minimal | Mild to severe | Visible blood |

| Pyrexia | No | No | Yes |

| Pulse >90 bpm | No | No | Yes |

| Anaemia | No | No | Yes |

| ESR (mm/hour) | ≤30 | 30 | >30 |

Table 2 – Truelove and Witt Criteria

Extra-Intestinal Manifestations

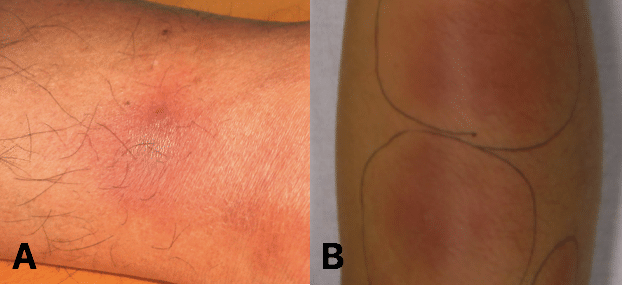

Ulcerative colitis, much like Crohn’s disease, is associated with certain extra-intestinal manifestations of the disease, occurring in 20 – 35% of cases and can precede intestinal symptoms in up to 25% of patients:

- Musculoskeletal, such as enteropathic arthritis (most common, typically affecting sacroiliac and other large joints), osteoporosis, or nail clubbing

- Skin, such as Erythema Nodosum (tender purple subcutaneous nodules, typically on the shins, Fig. 2) or pyoderma gangrenosum

- Eyes, such as episcleritis, anterior uveitis, or iritis

- Hepatobiliary, such as primary sclerosing cholangitis* (chronic inflammation and fibrosis of the bile ducts)

*Around 70% of patients with PSC will have IBD, whilst around 5% of patients with IBD will have PSC

Differential Diagnoses

The primary differential diagnosis for ulcerative colitis is Crohn’s disease. However, alternative forms of colitis include chronic infections (schistosomiasis, giardiasis, or abdominal tuberculosis), mesenteric ischaemia, or radiation colitis. Other differentials to consider include malignancy, irritable bowel syndrome, or coeliac disease.

Investigations

For patients with a suspected diagnosis of Ulcerative Colitis, routine blood tests can be performed, to assess for evidence of any anaemia, low albumin (secondary to systemic illness), or inflammation (raised CRP and WCC).

A faecal calprotectin test should be performed in all patents with recent onset lower gastrointestinal symptoms, which has a good sensitivity for inflammatory bowel disease. A stool MC&S sample should be sent to exclude an infective cause.

Imaging

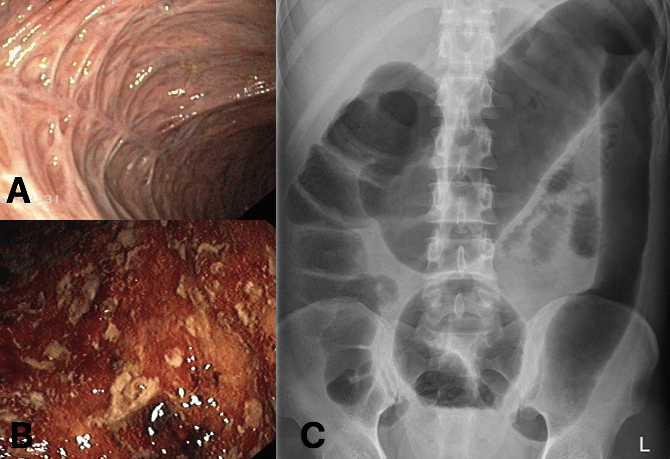

Colonoscopy with biopsies is the most sensitive and specific tool to establish a diagnosis of ulcerative colitis (Fig. 3A and 3B). Endoscopic views will show continuous and circumferential inflammation, with a clear demarcation of inflammation determining the extent of disease. Biopsies taken will help confirm the diagnosis (and exclude other causes of colitis, including CMV colitis).

Macroscopically, endoscopic findings in mild ulcerative colitis include erythema and vascular congestion, yet in moderate to severe disease there becomes a complete loss of vascular patterns and mucosal friability (Fig. 3B), with ulcer and pseudopolyp formation. The Montreal score can be used for quantifying disease extent and the Mayo score for disease severity.

In the acute setting, patients with an acute flare of Ulcerative Colitis may often require urgent CT imaging* (to assess for any evidence of bowel obstruction (from stricturing disease), toxic megacolon (Fig. 3C), or bowel perforation.

*Plain film abdominal radiographs (AXR) in an acute flare of ulcerative colitis may show mural thickening, thumb-printing, or, in chronic cases, a lead-pipe colon

Management

Any patients with suspected inflammatory bowel disease should be referred to Gastroenterology for confirmation of the diagnosis and initiation of treatment. Complex disease presentations may warrant discussion in a specific IBD MDT meeting, with involvement of gastroenterology, colorectal surgeons, radiologists, and dieticians.

All patients with UC should be referred to IBD nurse specialists and patient support groups. Enteral nutritional support should be considered, especially in young patients with growth concerns, and low residue diets can often be beneficial

Due to increased risk of colorectal malignancy, endoscopic surveillance is offered to people who have had the disease for >10 years with >1 segment of bowel affected (follow-up time frame depends on risk stratification of disease following initial endoscopy).

Medical Management

For mild to moderate disease, both induction and maintenance of remission can be managed with mesalazine, either as a suppository (for enema) for proctitis or as oral medication (for left sided or extensive colitis), for a few weeks. Patients who do not respond to mesalazine therapy should then be trailed on corticosteroids.

For moderate to severe disease, corticosteroids should be commenced. For those that improve, biologic agents, such as anti-TNF (e.g. infliximab) or vedolizumab, or thiopurines (e.g. azathioprine), can be used to maintain remission.

For acute severe ulcerative colitis, patient will often require hospitalisation to commence intravenous corticosteroid therapy. Those who fail to respond can be trialed on ciclosporin or infliximab therapy*. Such patients should also receive adequate fluid resuscitation and prophylactic heparin with anti-embolic stockings (due to the prothrombotic state of IBD flares).

*Surgical management is recommended if there is no improvement after 4–7 days of maximal medical treatment

Surgical Management

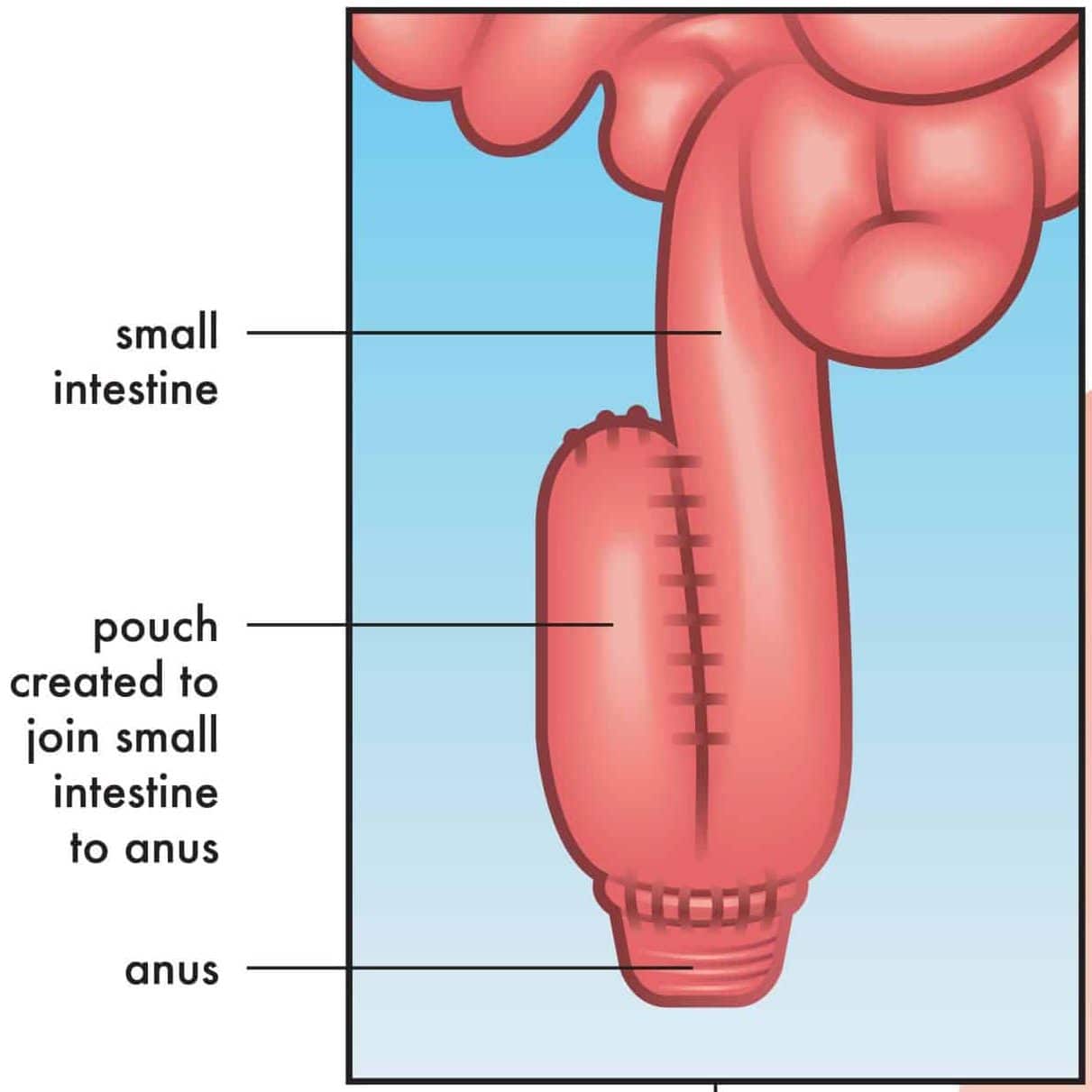

Over 10% patients with ulcerative colitis will require surgery in their lifetime. However, the surgery performed will depend on both patient and disease factors.

In the emergency setting, indications for surgery include toxic megacolon, colonic perforation, or uncontrolled bleeding. This is often either a segmental colectomy or subtotal colectomy with stoma formation. Up to 25% of all patients hospitalised for acute severe colitis will require a colectomy.

In the elective setting, indications for surgery include medically refractory disease, medication intolerance, or colorectal cancer (or endoscopically irresectable dysplasia).

A proctocolectomy and ileal-pouch anal anastomosis (IPAA) is often the surgical intervention of choice (Fig. 4), especially if keen to avoid a permanent stoma. This will require a staged surgical approach, conventionally a three stage approach to allow recovery between procedures and reduce patient morbidity: first stage is a subtotal colectomy with end ileostomy, second stage is a completion proctectomy and IPAA formation with a temporary loop ileostomy, and third stage is ileostomy reversal.

Proctocolectomy with end ileostomy is also a reasonable surgical option, with similar quality of life outcomes, requiring less operations and is not associated with any complications from an IPAA (see below).

Complications

Patients with well-controlled ulcerative colitis can expect to have a similar life expectancy as those in the general population.

However, the main complications of ulcerative colitis include:

- Toxic megacolon, present with severe abdominal pain, abdominal distension, pyrexia, and systemic upset

- Decompression of the bowel is required as soon as possible, due to high risk of perforation, and failure to respond to medical management is an indication for surgery

- Colorectal adenocarcinoma

- Pouchitis, inflammation of an ileal pouch in those who have undergone an IPAA, with typical symptoms of abdominal pain and bloody diarrhoea; this can be treated with metronidazole and ciprofloxacin

Key Points

- Ulcerative Colitis only affects the large bowel and definitive diagnosis is made from colonoscopy with biopsy

- Medical management of acute flares involves sequential escalation of treatment, from corticosteroids and immunosuppressors to biological therapies

- Surgical input should be sought urgently in cases refractory to medical management, patients who have developed toxic megacolon, or suspected bowel perforation

- Complications of the disease can be both intestinal and extra-intestinal manifestations