Introduction

Carotid artery disease refers to the build-up of atherosclerotic plaque in one or both common and internal carotid arteries, resulting in stenosis or occlusion.

The majority of carotid artery disease is asymptomatic, but it is also responsible for approximately 10-15% of ischaemic strokes, due to plaque rupture or atheroembolism.

In this article, we shall look at the clinical features, investigations, and management of a patient with carotid artery disease.

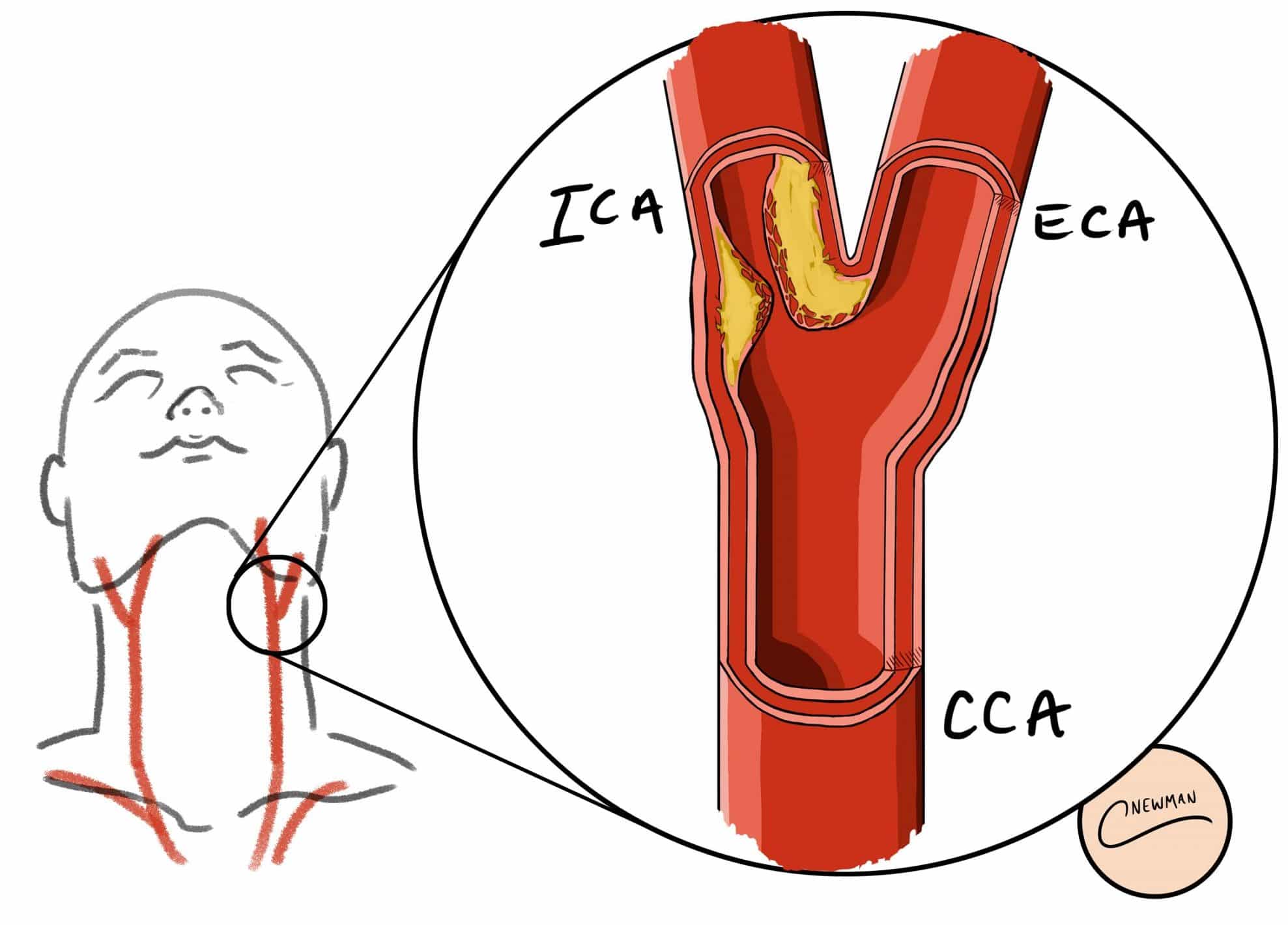

Figure 1 – Atherosclerotic plaque from a carotid endarterectomy

Classification

The pathophysiology of carotid artery disease is as for atheroma elsewhere, starting with a fatty streak, accumulating a lipid core and formation of a fibrous cap. The turbulent flow at the bifurcation of the carotid artery (Fig. 2) predisposes to this process specifically at this region.

Carotid artery disease is usually classified radiologically by the degree of stenosis:

|

Degree of Stenosis |

Diameter Reduction |

| Mild |

<50% |

| Moderate |

50-69% |

| Severe |

70-99% |

| Total Occlusion |

100% |

Table 1 – Classification of degree of carotid stenosis depending on diameter reduction

Risk Factors

The major risk factors for carotid artery disease are age (≥65 years), smoking, hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, obesity, diabetes mellitus, history of cardiovascular disease, and a family history of cardiovascular disease.

Clinical Features

Carotid artery disease will often be asymptomatic, however may present as a focal neurological deficit. This can take one of two forms:

- Transient ischaemic attack (TIA) – lasts less than 24 hours before full resolution*

- Stroke – lasts for more than 24 hours without full resolution

*This may include transient visual loss, termed amaurosis fugax

Much of the detailed initial assessment for a patient presenting with a stroke is typically beyond the scope of a vascular surgeon. The Oxford Stroke (Bamford) Classification provides a system to classify the clinical features of a stroke in relation to the arterial regions involved (see Appendix).

On examination of the vascular system, a carotid bruit may be auscultated in the neck (however this is associated with carotid stenosis in less than half of cases)*.

*Aside from the clinical features from stroke, carotid stenosis (even with complete occlusion) is likely to be asymptomatic if unilateral; this is due to collateral supply from the contralateral internal carotid artery and the vertebral arteries, via the Circle of Willis

Differential Diagnoses

Atherosclerosis is the most common form of carotid artery disease. However, there can be other pathologies involved:

- Carotid Dissection – Patients are often younger (<50yrs) and have an underlying connective tissue disease, with the event potentially precipitated by trauma or sudden neck movement

- Thrombotic Occlusion of Carotid Artery – Thrombus can only be differentiated from atheromatous plaque on imaging and will present clinically as for atheroma

- Fibromuscular Dysplasia – This is non-atheromatous stenotic angiopathy causing hypertrophy of the vessel wall, predominantly affecting young (<50yrs) females and, whilst most commonly in the renal arteries, the carotid arteries can be affected, presenting clinically with focal neurological deficit

- Vasculitis – Various great vessel vasculitidies, such as Giant Cell Arteritis or Takayasu’s Arteritis, can cause carotid stenoses, however patients typically have systemic symptoms and other vessels may be affected

In addition, non-cerebrovascular conditions that manifest neurologically should be considered. These include hypoglycaemia, Todd’s paresis*, subdural haematoma, space-occupying lesion, venous sinus thrombosis, post-ictal state, and multiple sclerosis.

*Todd’s Paresis = Unilateral motor paralysis following a seizure

Investigations

Initial Investigations

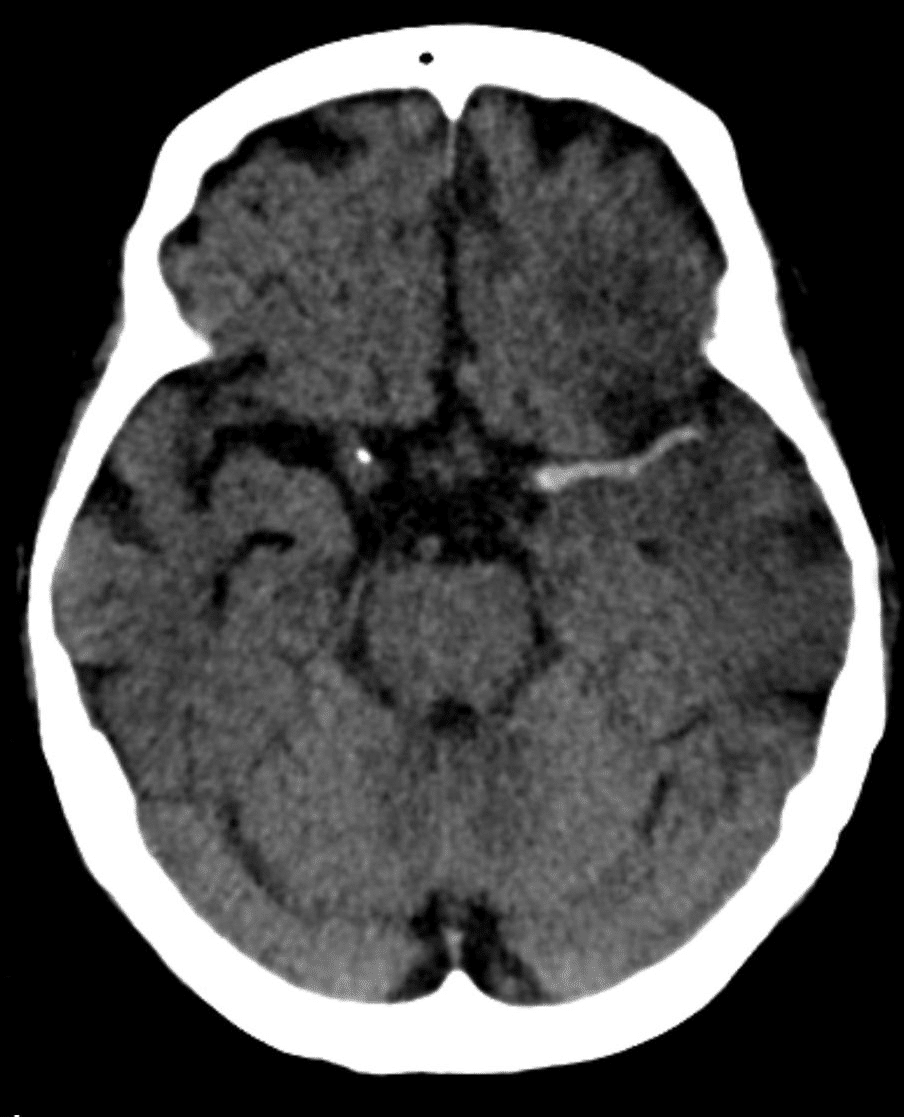

Any patient suspected of ischaemic (or haemorrhagic) stroke should have an urgent non-contrast CT head scan (Fig. 3), assessing for evidence of infarction potentially amenable to thrombolytic treatment.

Other investigations for a patient admitted with a stroke include:

- Bloods, including FBC, U&Es, clotting, lipid profile, and glucose

- Electrocardiogram (ECG), especially to check for atrial fibrillation or other rhythm abnormalities

If thrombectomy is considered in patients with evidence of ischaemia, imaging via CT angiography is often also required

Figure 3 – CT head scan showing hyperdense artery sign in a patient with middle cerebral artery infarction

Follow-up Investigations

Once a diagnosis of ischaemic stroke or TIA is made, it is important to screen the carotid arteries for disease precipitating the presentation. This can be done initially with Duplex ultrasound scans, which gives a good estimate as to the degree of stenosis, as well as excluding any other possible differentials.

Lesions within the carotid artery may then be further characterised via CT angiography, which gives a more accurate assessment of the diseased portion of the vessels prior to any potential surgery.

Management

Acute Management

All patients admitted with a suspected stroke should be started on high flow oxygen and blood glucose optimised (target 4-11mmol); a swallowing screen assessment should also be made on admission.

Initial management depends on the nature of the stroke:

- Ischaemic stroke – Intravenous alteplase (r-tPA), if patients are admitted within 4.5hrs of symptom onset and meet inclusion criteria, and 300mg aspirin (usually orally, or given rectally if dysphasic)

- Haemorrhagic stroke – correction of any coagulopathy and referral to neurosurgery (for potential clot evacuation*)

Thrombectomy is indicated in patients with confirmed acute ischaemic stroke and confirmed occlusion of the proximal anterior circulation on angiography, as well as consideration for intravenous thrombolysis too.

*Neurosurgery is often not advised for a haemorrhagic stroke, unless superficial lobar bleed or ventricular bleed, yet this will be at the neurosurgeon’s discretion

Long Term Management

All patients with a known stroke or TIA should also be started on cardiovascular risk factor management:

- Anti-platelet therapy long term, typically aspirin 300mg OD for two weeks, then clopidogrel 75mg OD

- If not tolerated, trial combination therapy aspirin and dipyradimole

- Statin therapy, ideally high-dose atorvastatin (started after the hyperacute phase)

- Aggressive management of hypertension and/or diabetes mellitus

- Smoking cessation

- Regular cardiovascular exercise and active lifestyle with weight loss

A referral to the Speech and Language Therapy (SALT) team is advised for any dysphagia or dysphasia. Physiotherapy and Occupational Therapy input is advised for any ongoing mobility issues, with many stroke patients requiring rehabilitation.

Carotid Endarterectomy

All patients with an acute non-disabling stroke (or transient ischaemic attack) who have symptomatic carotid stenosis between 50 – 99% should be referred for assessment for a carotid endarterectomy (CEA)*

Patients who are suitable for surgery should be operated on within the first 2 weeks following their symptoms. Surgery typically halves the risk of a future stroke; tools such as the Oxford Vascular Carotid Stenosis Risk Score can be used to help determine the risk of future stroke.

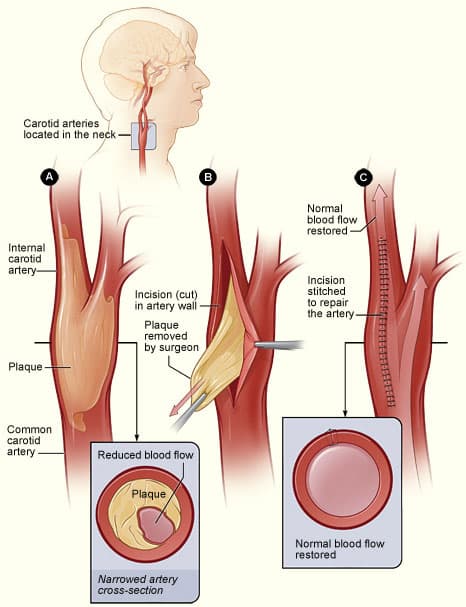

CEA involves removing the atheroma and associated damaged intima (Fig. 4), thereby reducing the risk of future strokes or TIAs. Risks of CEA surgery include ischaemic stroke (2-3%) and nerve damage to the hypoglossal, glossopharngeal, or vagus nerve.

*CEAs are now seen as a superior option to carotid stenting, with the latter associated with an increased risk of long-term major adverse events

Complications

Mortality following a stroke is around 12% at 7 days and nearly 20% at 30 days. Other complications of a stroke include long-term dysphagia, seizures or ongoing spasticity, bladder or bowel incontinence, and depression, anxiety, or cognitive decline.

The most significant improvement from rehabilitation occurs between 4-6 weeks, yet 50% of stroke patients will remain dependent at 1 year.

Key Points

- Most cases of carotid artery stenosis are asymptomatic, however the major sequela of the condition is ischaemic stroke

- First line investigation is via carotid US Doppler, with confirmed cases being further assessed with CT angiography

- Selected cases will be offered carotid endartectomy (CEA) for risk reduction management of ischaemic stroke

Appendix – The Oxford Stroke Classification

| Classification | Description | Signs and Symptoms |

| Total Anterior Circulation Stroke (TACS) (20%) | Large cortical stroke in middle or anterior cerebral artery areas | Must have all of:

|

| Partial Anterior Circulation Stroke (PACS) (35%) | Cortical stroke in middle or anterior cerebral artery areas | Will present with either:

|

| Lacunar Stroke (LACS) (20%) | Occlusion of the deep penetrating arteries | Will present with any of:

|

| Posterior Circulation Stroke (POCS) (25%) | Occlusion of vertebrobasilar or PCA circulation, affecting brainstem, cerebellum, or occipital lobe | Variety of presentations can occur, typically:

|