Introduction

Cauda equina syndrome (CES) is a surgical emergency caused by a compression of the cauda equina. If untreated, patients can develop debilitating complications, hence a high level of suspicion and rapid intervention is required.

The condition has peak onset between 40-50 years of age. Approximately 4 in every 10,000 patients presenting with lower back pain are ultimately diagnosed with the syndrome.

In this article, we shall look at the pathophysiology, clinical features, and management of cauda equina syndrome.

The Cauda Equina

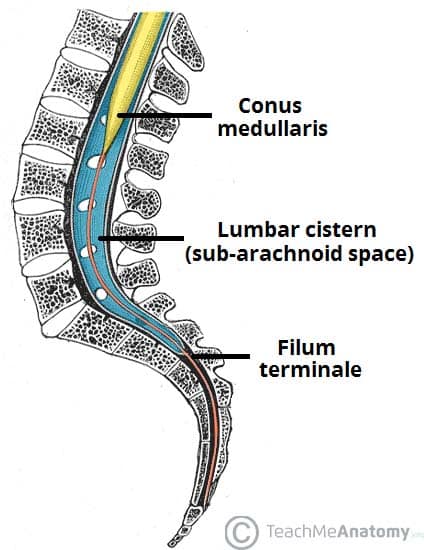

The cauda equina is a bundle of nerves situated inferior to the spinal cord.

The spinal cord tapers to an end (known as the conus medullaris), approximately at the first lumbar vertebra, with nerve roots L1-S5 leaving from at this region to pass down the spinal canal (as the cauda equina) to exit at their respective formaina.

Consequently, the cauda equina is formed by lower motor neurones, containing motor and sensory impulses to the lower limbs, motor innervation to the anal sphincters, and parasympathetic innervation for the bladder.

Pathophysiology

Cauda equina syndrome is caused by compression of the cauda equina:

- Disc herniation (most common cause) – most commonly occuring at L5/S1 and L4/L5 level

- Trauma – including vertebral fracture and subluxation

- Neoplasm – either primary or metastatic

- The most common cancers that spread to spinal vertebrae are thyroid, breast, lung, renal and prostate

- Infection – e.g. discitis or Potts disease

- Chronic spinal inflammation – e.g. ankylosing spondylitis

- Iatrogenic – e.g. haematoma secondary to spinal anaesthesia

Clinical Features

Cauda equina syndrome results in lower motor neurone signs and symptoms.

Symptoms include reduced lower limb sensation (often bilateral), bladder or bowel dysfunction, lower limb motor weakness, severe back pain, and impotence.

An important feature to assess is bladder dysfunction, specifically the presence of retention. Confirmed retention or reduced ability to void (loss of desire, reduced urinary sensation) suggests complete or incomplete CES respectively. Similarly, bowel incontinence should be investigated during the history taking.

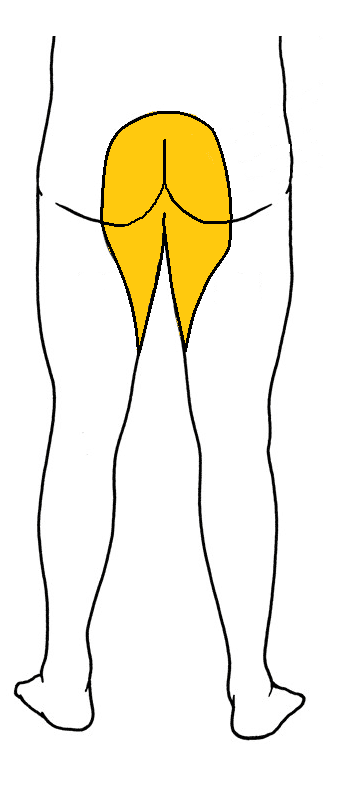

On examination, features include perianal (the lower sacral dermatomes, termed “saddle” anaesthesia) or lower limb anaesthesia, loss of anal tone, urinary retention, and lower limb weakness and hyporeflexia.

If no obvious cause is evident, a thorough history and examination may reveal the pathophysiology, such as weight loss as a sign of metastatic disease or living in an area of endemic tuberculosis.

As part of the examination for suspected CES, regardless of symptoms, patients will require a PR examination and a post-void bladder scan.

Full peripheral neurological examination, including of the upper limbs, is required to look for spinal pathologies higher up along the spine than the cauda equina; if there is suspicion of pathology in other spinal segments, a whole spine MRI will be indicated instead.

Classification

Cauda Equina Syndrome can be classified into 3 groups:

- Cauda Equina Syndrome with retention (CESR) – Presents as back pain with unilateral or bilateral sciatica, lower limb motor weakness, sensory disturbance in the saddle region, loss of anal tone, and loss of urinary control

- Incomplete Cauda Equina Syndrome (CESI) – As above, however only altered urinary sensation (e.g. loss of desire to void, diminished sensation, poor stream, and need to strain); painful retention may precede painless retention in some cases

- Suspected Cauda Equina Syndrome (CESS) – Cases of severe back and leg pains with variable neurological symptoms and signs, and a suggestion of sphincter disturbance

Most cases will be progressive in nature and will cause complete compression on the cauda equina if left untreated. This is important for the management, as incomplete cauda equina syndrome has a greater potential for neurological recovery. Additionally, speed of symptom onset is important, as acute rather than subacute onset has a better prognosis when promptly treated.

Differential Diagnosis

- Radiculopathy – presents with radiating back pain, however there will be no faecal, urinary, or sexual dysfunction in these patients

- Cord compression – a surgical emergency with a similar pathophysiology to CES, however is characterised by upper motor neurone signs

- Muscloskeletal pain – relating to strain of paraspinal muscles, with severe pain that may lead to limited movement, but no other focal neurological signs

Investigations

For suspected cases of cauda equina syndrome, an emergency lumbar-sacral spine MRI (Fig. 3) is the gold standard investigation. However, only a minority of patients suspected to have CES from clinical assessment have an abnormality found on MRI.

Further imaging may be required dependent on the underlying cause, however if CES is confirmed, then urgent surgical intervention is the priority.

Management

An early neurosurgical review for urgent decompression must be initiated, especially for those with incomplete CES as the prognosis is potentially more favourable.

All acute CES patients will usually be recommended for surgical decompression, aiming to prevent permanent sphincter and lower limb dysfunction – this intervention should take place as soon as possible, including out of hours. The neurosurgical team will discuss plans for surgical decompression, risks and benefits with the patient.

In certain rarer situations, such as malignancy, radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy may be used (especially if the patient is not suitable for surgery) after consultation with specialist teams.

Prognosis

The prognosis of cauda equina syndrome is variable depending on both aetiology and the time taken from symptom onset to surgery.

Indeed, a retrospective study examined the case for early surgery and found that patients who were in theatre within 24 hours from onset of autonomic dysfunction had reduced bladder problems at long-term follow up.

Key Points

- Cauda equina syndrome is a surgical emergency caused by a compression of the cauda equina

- CES results in lower motor neurone signs and symptoms

- Any suspected cases require an urgent lumbar-sacral spine MRI scan

- An early neurosurgical review for urgent decompression is required for confirmed cases