Introduction

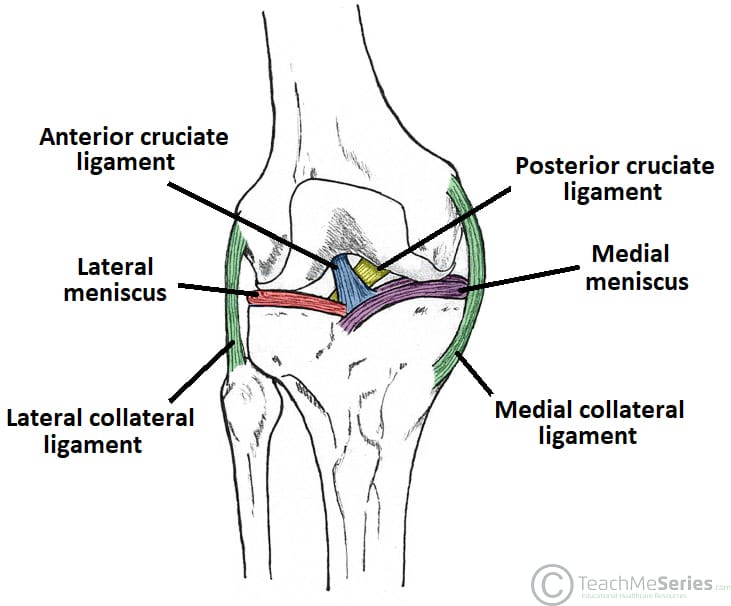

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is the most commonly injured ligament of the knee*.

The MCL primary function is to act as a valgus stabiliser of the knee and is most often injured when external rotational forces are applied to the lateral knee, such as a impact to the outside of the knee.

MCL injuries can be graded from one to three:

- Grade I – mild injury, with minimally torn fibres and no loss of MCL integrity

- Grade II – moderate injury, with an incomplete tear and increased laxity of the MCL

- Grade III – severe injury, with a complete tear and gross laxity of the MCL

*Isolated injuries of the LCL are rare and go beyond the scope of this article

Clinical Features

A medial collateral ligament tear will typically occurs after trauma to the lateral aspect of the knee.

In isolated medial collateral ligament tears, this is usually a direct blow in a valgus stress direction. Non-contact MCL injuries occur less commonly, and often arise from a valgus stress with external rotation force, such as in skiing.

The patient may report hearing a ‘pop’ with immediate medial joint line pain. Swelling tends to follow after a few hours (unless there is an associated haemarthrosis, in which case it will occur within minutes).

The main clinical finding on examination will be increased laxity when testing the MCL*, via the valgus stress test. The patient will be extremely tender along the medial joint line, but may be able to weight bear.

*A Grade II and III tear can be distinguished clinically on medial stress testing; Grade II is lax in 30 degrees of knee flexion but solid in full extension, whereas Grade III is lax in both these positions.

Differential Diagnosis

In the acutely swollen knee following trauma, the main differentials to consider include fractures, meniscal injury, and multi-ligament tears (particularly MCL & ACL).

Investigations

Any patient following trauma with significant knee pain and swelling should have a plain film radiograph to exclude any fracture.

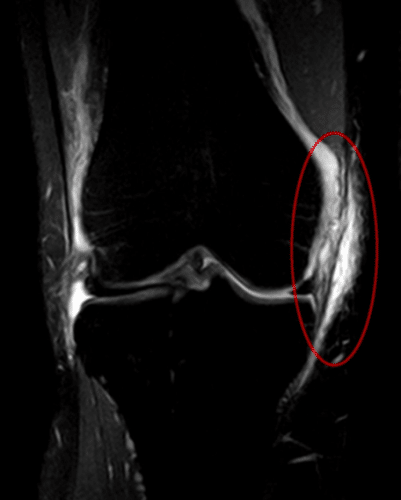

The gold-standard investigation to confirm the diagnosis for an MCL tear is via MRI scanning (Fig. 2), delineating the exact extent and grade of the tear.

Management

The management of an MCL injury is dependent on the grade of injury:

- Grade I Injury: Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation (RICE) with analgesia (typically NSAIDs) as the mainstay. Strength training as tolerated should be incorporated, with an aim to return to full exercise within around 6 weeks.

- Grade II Injury: Analgesia with a knee brace and weight-bearing/strength training as tolerated. Patients should aim to be able to return to full exercise within around 10 weeks

- Grade III Injury: Analgesia with a knee brace and crutches, however any associated distal avulsion then surgery is considered. Patients should aim to be able to return to full exercise within around 12 weeks.

Complications

The main complications following a MCL tear are instability in the joint and damage to the saphenous nerve.

Key Points

- The medial collateral ligament is the most commonly injured ligament of the knee

- Typically occurs following trauma to the lateral aspect of the knee, presenting with immediate medial joint line pain and an associated ‘pop’ heard

- Definitive diagnosis is made via MRI scanning

- Management for MCL injury depends on the grade of the tear