Introduction

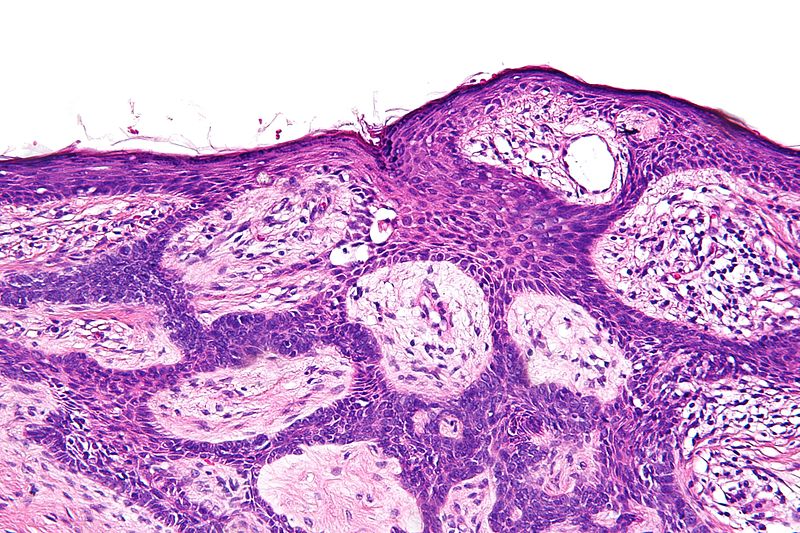

Basal cell carcinoma (BCC) is a slow-growing and locally-invasive skin cancer that arises from the pluripotent cells of the stratum basale layer of the epidermis.

BCC is the most common form of skin cancer, however fortunately it is the least likely to metastasise (<0.5% risk). The overall incidence is increasing worldwide, with a lifetime risk of 23-39% in Caucasian patients.

Risk Factors

Most BCCs are associated with long-term UV exposure, especially repeated sunburn during childhood. UV exposure leads to genetic mutations in DNA (specifically on the p53 tumour suppressor 9q22).

Other risk factors include PUVA therapy for psoriasis, Fitzpatrick type 1 skin, immunosuppression (e.g. transplant patients have a 10-fold increased risk), and genetic syndromes (such as Xeroderma Pigmentosa or Gorlin syndrome).

Clinical Features

The majority of BCCs will occur on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck, with the remainder mainly occurring on the trunk or lower limbs.

They present typically as small slow-growing lesions, with raised pearly edges and evident telangiectasia (Fig. 2). They rarely cause symptoms initially, aside from aesthetic changes.

However, if left to grow, they can cause symptoms such as pain, bleeding, and ulceration, or subsequent local invasion into surrounding tissues.

Figure 2 – Examples of Basal Cell Carcinoma

Subtypes

There is a range of different presentations of BCC, depending on the subtype:

- Nodular – most common (50-60%), commonly a pink pearly nodule with telangiectasia, and can become ulcerated or encrusted; subtypes include cystic, pigmented, or keratotic

- Superficial – (10-15%) erythematous scaly plaques with a thread-like border, and may bleed or ulcerate

- Morphoeic – more uncommon, presenting as thickened and sclerosing plaques with poorly defined borders; highest risk of incomplete excision and often prone to recurrence after treatment

- Basosquamous – a mixed basal cell and squamous cell malignancy, with an infiltrative growth pattern and often are more aggressive

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnoses to consider for a patient presenting with a lesion suspicious for a BCC include Trichoepithelioma (a rare benign tumour of the hair follicle), Keratoacanthoma (rapidly-growing tumour of the skin derived from the glands surrounding a hair follicle), or a cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma.

Investigations

Although BCC is usually diagnosed clinically, it can only be confirmed through excision biopsy (discussed below)*.

Dermatoscope examination can aide the clinician with diagnosis, as under the dermtoscope features of the lesion can be seen that make the diagnosis of BCC more probable (such as arborising vessels, spoke wheel like structures, areas of ulceration).

No further investigation is usually required unless there are features of invasion into underlying structures or metastasis, where additional radiological imaging would be appropriate.

*In clinically indistinct larger lesions, those close to crucial anatomical structures, or atypical looking lesions, an incisional tissue biopsy can be performed primarily to obtain histopathological diagnosis prior to further treatment

Management

Factors such as tumour subtype, size, anatomical location, and histological diagnosis will impact how a BCC is managed:

- Low-risk BCCs are small, well-circumscribed lesions superficial type lesions that do not meet any of the high-risk criteria

- High-risk BCCs include those occurring in the young (<25yrs) or immunocompromised patients, recurrent lesions, lesions on the nose, lips, ears, or around the eyes, lesions with poorly defined margins, and all non-nodular subtypes of BCC

Multiple management options are available BCCs. Superficial disease can often be treated with non-surgical options alone, which include:

- Cryotherapy (or CO2 ablation)

- Curettage and electrodissection – 75% cure rate (95% for smaller lesions <2cm)

- Immune response modulator – Topical imiquimod 5% cream (for superficial BCCs)

- Topical chemotherapy – 5-fluorouracil 5% cream (for superficial BCCs)

- Photodynamic therapy – Uses light therapy together with a topical photosensitising agent (for superficial BCCs)

- Radiotherapy – usually reserved for the older age group, achieves ~90% cure rates

Surgical Management

The mainstay of surgical management is with excision biopsy. The margins required are between 3-5mm, depending on how demarcated the border is and the location of the lesion. Higher excision margins are required for recurrent BCCs (5mm) or high-risk histological subtypes.

If there is sufficient skin laxity in the region, the defect can be closed directly. However, some may require local, regional or free flap or skin grafts.

Lesions which are close to vital anatomical structures, have indistinct margins, or are recurrent should be considered for Mohs’ micrographic surgery.

Mohs’ Micrographic Surgery

Mohs’ micrographic surgery is a tissue preserving technique which removes the lesion whilst assessing the entire excision margins.

The tumour is initially debulked, and then saucer-shaped 1mm layers of tissue are excised at a time. Each layer is then immediately checked under a microscope by a trained technician, and the process is continued until the tumour has been fully removed.

Mohs’ micrographic surgery is particularly useful in (1) recurring or incompletely removed BCC, (2) areas where it would be cosmetically better to remove as little skin as possible (3) at sites of previous surgery or radiotherapy.

Overall cure rates are high for both primary (99%) and recurrent (95%) tumours using Mohs’ micrographic surgery.

Prevention

Prevention advice is vital in managing skin cancer patients. Patients should be encouraged to reduce their exposure to UV light and avoid sunbeds (primary prevention) and advised on the frequent use of SPF50 sunscreen and wearing of protective clothing (secondary prevention).

Prognosis

As BCCs rarely metastasis, prognosis is generally good. Incomplete excision rates vary between 4% – 11% (more common for periorbital and nasal lesions) and incompletely excised BCCs generally have a 30-40% recurrence rate.

Risk factors for incomplete excision include head lesions, certain histological subtypes (morphoeic, superficial, infiltrative), >2cm lesions, or recurrent lesions. For those patients who do develop recurrence, less than a third develop at one year, 50% at two years and 66% at three years.

Patients who have had a BCC have a 35% risk of developing another non-melanoma skin cancer in 3 years and 50% risk in 5 years.

Key Points

- Basal cell carcinoma is a slow-growing and locally-invasive skin cancer

- The majority of BCCs will occur on sun-exposed areas, presenting as small slow-growing lesions, with raised pearly edges and evident telangiectasia

- They are diagnosed clinically and confirmed following excision biopsy

- Multiple management options are available BCCs and prognosis is generally good