Introduction

Otitis externa is an infection of the external ear, a common condition that is mainly seen in primary care.

Whilst it typically settles with simple intervention of topical antibiotics, there are certain complications that occur otitis externa that can require.

In this article, we shall look at the causes, clinical features and management of otitis externa.

Pathophysiology

Otitis externa typically affects the external auditory canal, the part of the ear via which sound waves travel to reach the tympanic membrane.

Any interruption in wax formation (e.g. repeated water exposure), trauma to the canal (e.g. cotton buds), or blockage (e.g. debris) can disrupt the external auditory canal’s protective mechanisms and lead to pathogen overgrowth and inflammation.

The skin becomes erythematous, swollen, tender, and warm, leading to debris and discharge accumulation. The narrowing of the canal, in combination with the accumulation of debris, leads to further entrapment of pathogens and propagating the infective process.

The most common causative pathogens include Pseudomonas Aeruginosa (around 40%), S. Epidermidis, S. Aureus, and anaerobes. In rarer cases, it can be due to a fungal infection (typically Aspergillus spp. or Candida).

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for otitis externa are those that interfere with the normal protective mechanisms of the external auditory canal:

- Frequent water contact (e.g. swimmers and frequent hair washers)

- Humid environments

- Presence of ear polyps or foreign bodies (e.g. hearing aids)

- Ear eczema or psoriasis

- Local trauma (e.g. hearing aids or excessive use of cotton buds)

Immunocompromised individuals, including patients with diabetes mellitus, are at increased risk of otitis externa. These patients are also at a higher risk of complications, such as malignant otitis externa, therefore extra care must be taken when treating these patients.

Clinical Features

The classical clinical picture of otitis externa is progressive ear pain with a purulent discharge (Fig. 2), alongside itchiness or fullness. Less common symptoms include hearing loss, tinnitus, or vertigo.

Ensure to ask about systemic symptoms, such as fever or malaise, as well as potential precipitants or risk factors for otitis externa (as mentioned above).

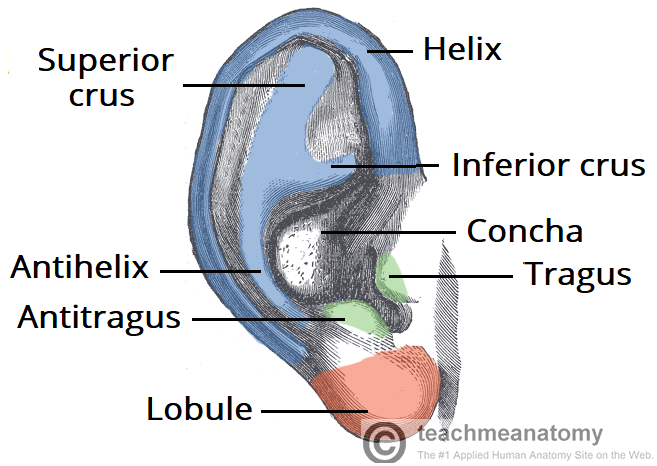

On examination, the external ear canal will appear swollen and erythematous. The pinna may be swollen and the tragus is usually tender on palpation. There may be dry discharge noted on the concha bowl.

Any discharge is usually purulent, the colour of which may indicate the underlying cause*. Ensure to check for any erythema on the face as there might be spreading facial cellulitis. Vesicles can be seen if there is a concurrent viral (e.g. Herpes Simplex or Varicella Zoster) cause to the otitis externa.

*White-yellow discharge is often related to bacterial infection, whilst a thick white-grey discharge with visible hyphae or spores may suggest a fungal infection

Differential Diagnosis

Important differentials to consider for anyone presenting with purulent ear discharge include:

- Otitis media with perforation – usually clear discharge or bloody followed by relief of pain, with an inflamed tympanic membrane with perforation on examination.

- Ramsay-Hunt syndrome – may present with symptoms of otitis externa, yet has evidence of vesicular eruptions within 2 days of first onset of pain

- Furuncle – a painful ear canal due to localised abscess formation from infection of the hair follicle in the lateral third of ear canal; a visible bulge is present when examining with an otoscope

Less common conditions include ear canal malignancy, branchial cyst, atopic dermatitis, or exostosis.

Investigations

Otitis externa is usually a clinical diagnosis, based on a thorough history and examination of the ear using an otoscope.

If otitis externa is not resolving with antibiotics or there are signs of fungal disease on otoscopy, swabs of the discharge can be sent for culture. In recurrent disease, it may be useful to check glucose levels for diabetes mellitus.

In complicated cases of otitis externa (discussed below), a High Resolution CT scan (HRCT) of the mastoid and temporal bones is often warranted to investigate the extent of the disease.

Risk Scoring

The Brighton Grading Scheme can be used to quantify the severity of otitis externa:

| Brighton Grade | Description |

| Grade I | Localised canal inflammation with mild pain, no hearing loss and tympanic membrane visible |

| Grade II | Debris in ear canal (not completely occluded) and erythematous ear canal, tympanic membrane may be partially obscured |

| Grade III | The ear canal is oedematous, erythematous, and occluded (often completely closed), and the tympanic membrane cannot be seen |

| Grade IV | The tympanic membrane is obscured, perichondritis and pinna cellulitis, and signs of systemic involvement. |

Management

The mainstay of management in otitis externa involves prevention, topical antibiotics, and simple analgesia.

No single topical antibiotic regime has been found to be superior*, thus the antibiotic choice depends on the patient and doctor preference, local sensitivities and adverse reactions.

Steroid drops have been shown to be beneficial when there is evidence of canal inflammation. It acts to decrease the swelling (allowing the antibiotic to perforate) and reduce pain.

Any purulent discharge in the ear canal should be micro-suctioned, as this ensures topical ear drops will be able to act on the bacteria within the ear canal.

If the ear canal is extremely swollen, a pope ear wick should be inserted to ensure the topical ear drops are able to penetrate into the ear canal. This should remain in place for 2 days, and the patient seen again in clinic for removal of the pope wick.

*Oral antibiotics have not been shown to offer any benefit in uncomplicated otitis externa and are usually avoided (unless evidence of cellulitis or pinna involvement)

Prevention

Following treatment, the patient should be advised to avoid exacerbating factors, such as swimming, and advising the patient to keep their ears dry. Any underlying eczema or polyps should be managed as required.

If the patient has recurrent otitis externa secondary to using a standard hearing aid, they should consider a bone-anchored hearing aid instead, as this allows the external ear canal to ventilate better and prevent accumulation of debris and wax.

Complications

Otitis externa usually resolves with topical antibiotics. However, in cases of delayed presentation, resistant organism or immunocompromised patient, it may extend to a more severe infection.

If the infection persists despite multiple courses of topical antibiotics, or if the patient develops local complications or has severe systemic infective symptoms, referral to an ENT specialist is required. Potential complications of otitis externa include facial cellulitis, malignant otitis externa, mastoiditis, osteomyelitis, and intracranial spread.

Otitis externa with facial cellulitis is when otitis externa spreads into the fascial layers of the face. Patients with this require intravenous antibiotics and typically a pope wick placed as the ear canals are often too swollen for drops. Close monitoring its spread is essential.

Malignant Otitis Externa

Malignant otitis externa is an extension of otitis externa into the mastoid and temporal bones, resulting in skull base osteomyelitis. It typically occurs in older, diabetic, or immunocompromised patients.

Patients present with severe otalgia, which is particularly worse at night and affects their sleep. On examination of the ear canal, granulation tissue along the bony-cartilaginous junction is evident and microsuction attempts are often challenging due to severe pain.

These patients require an urgent HRCT scan of the temporal bones for a formal diagnosis. They will require long-term intravenous antibiotics (for at least 6 weeks) and repeated assessment in ENT clinic weekly with regular microsuctions.

Malignant otitis externa can progress to result in facial nerve palsy or spread intracranially, resulting in meningitis or cranial abscess.

Key Points

- Otitis externa is an infection of the external ear, commonly presenting with progressive ear pain and a purulent discharge

- Diagnosis is usually clinical however any suspicion of complicated disease warrants imaging with a HRCT scan

- Mainstay of management in otitis externa involves prevention, microsuction, topical antibiotics, and simple analgesia

- Most cases of otitis externa resolve with simple measures however malignant otitis externa need to be identified and treated urgently to prevent any further complications