Introduction

A facial palsy is weakness or paralysis of the muscles of the face. Whilst the majority of cases are idiopathic, termed Bell’s Palsy, there are a wide range of potential causes of a facial palsy.

The first distinction to be made is with upper motor neuron (UMN) and lower motor neuron (LMN) facial palsy; forehead sparing indicates UMN palsy and forehead paralysis LMN palsy.

Bell’s palsy is an idiopathic LMN facial palsy. It is a diagnosis of exclusion and hence all possible causes have to be excluded first prior to diagnosing Bell’s palsy. The majority of this article will discuss Bell’s Palsy and its associated clinical features and management.

Anatomy of the Facial Nerve

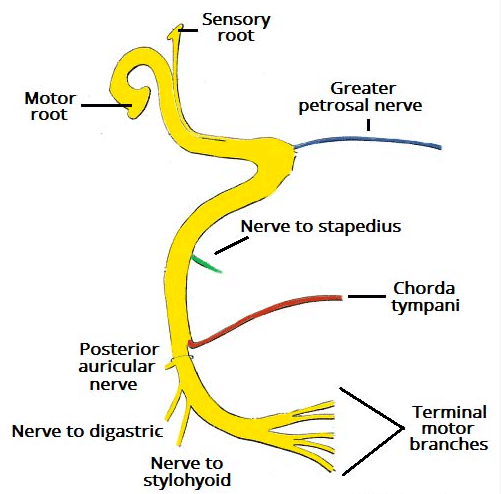

The facial nerve arises in the pons (formed as separate sensory and motor roots), before travelling in the internal acoustic meatus, very close to the inner ear. As they enter the facial canal, the two roots fuse to form a single facial nerve, before giving off intracranial branches of the greater petrosal nerve, nerve to stapedius, and chorda tympani.

The facial nerve travels through the middle ear cavity in the facial canal and then through the mastoid bone. Finally, in exits the cranium via the stylomastoid foramen.

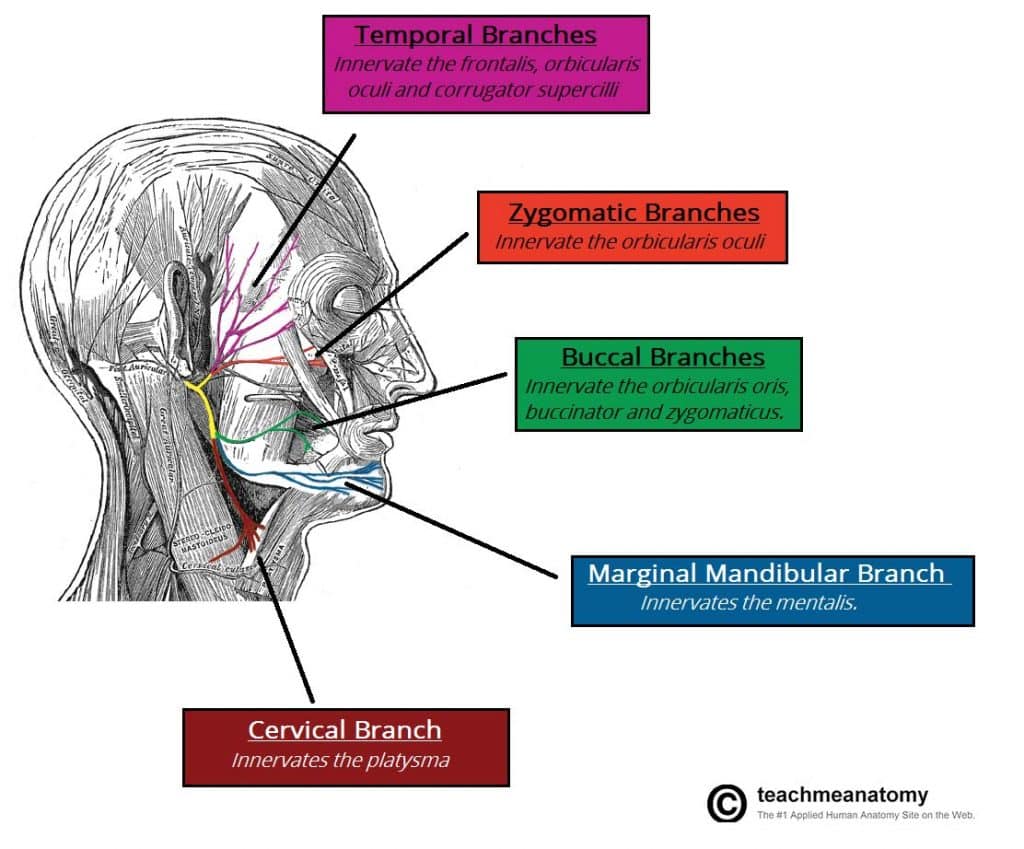

The first extracranial branches given off are the posterior auricular nerve, nerve to digastrics, and nerve stylohyoid. The facial nerve then enters the parotid gland, dividing into terminal branches of the Temporal, Zygomatic, Buccal, Marginal mandibular, and Cervical branches.

Pathophysiology

Bell’s palsy remains a poorly understood condition. Many causative associations have been proposed, the most universally accepted theory suggests a viral origin, yet no conclusive evidence is available at present.

The main risk factor for developing Bell’s palsy is known concurrent viral infection, such as HSV-1, CMV, and EBV, whilst less common risk factors include diabetes mellitus and pregnancy.

Clinical Features

Patients with a Bell’s Palsy will present with varying severity of painless unilateral lower motor neuron (LMN) weakness of the facial muscles (Fig. 2).

Depending on the severity and the proximity of the nerve affected, it can also result in:

- Inability to close their eye (temporal and zygomatic branches)

- Hyperacusis (nerve to stapedius)

- Metallic taste (chorda tympani)

- Reduced lacrimation (greater petrosal nerve)

To distinguish clinically between a LMN cause and UMN cause of the facial palsy, a patient with forehead sparing (i.e. no involvement to the occipitofrontalis muscle) will have a UMN origin to the palsy, due to the bilateral innervation of the forehead muscle).

Severity Grading of a Facial Palsy

The House-Brackmann classification is used to grade the severity of facial nerve palsy. It is an objective scale that can be repeated over time, assessing for any response to treatment:

| Grade | Description | Characteristics |

| I | Normal | Normal facial function in all areas. |

| II | Mild Dysfunction | Slight weakness noticeable on close inspection; may have very slight synkinesis. |

| III | Moderate Dysfunction | Obvious, but not disfiguring, differences between 2 sides. Noticeable, but not severe, synkinesis or hemifacial spasm. Complete eye closure with effort. |

| IV | Moderately Severe Dysfunction | Obvious weakness of disfiguring asymmetry, normal symmetry and tone at rest but unable to complete eye closure. |

| V | Severe Dysfunction | Only barely perceptible facial muscle motion, asymmetry at rest. |

| VI | Complete paralysis | No movement |

Differential Diagnosis

Important differential diagnosis for a facial palsy, other than Bell’s Palsy, include:

- UMN causes, such as a stroke, subdural haematoma, multiple sclerosis, or neoplasm (e.g. a primary brain malignancy)

- The will present with forehead sparing

- LMN causes

- Infective, such as acute otitis media, cholesteatoma, viral infection (including HSV-1, CMV, and EBV)

- Neoplasm (e.g. parotid malignancy)

- Trauma (e.g. temporal bone fracture) or iatrogenic (e.g. mastoid or parotid surgery)

Figure 2 – Involvement of the forehead seen in a case of Bell’s Palsy

Investigations

Most cases of Bell’s Palsy can be diagnosed clinically and no further investigations are required, unless any other clinical features are present that suggest another pathology.

Serology for HSV-1 and VZV can be performed, yet will unlikely alter future management if detected. This is particularly relevant where vesicular pustules are evident.

Management

Patient reassurance is essential, as most cases return spontaneously to full function.

Eye care is one of the most important aspect of the management, ensuring the patient uses lubricating drops hourly, use of eye ointment at night and taping of the eye at night time. An ophthalmology review is recommended.

All patients presenting within 72 hours of symptoms onset should be started oral steroids. Current guidance recommends either:

- Giving 25 mg twice daily for 10 days

- Giving 60 mg daily for five days followed by a daily reduction in dose of 10 mg

Use of anti-viral agents is controversial. A Cochrane Review found low level evidence that the combination of anti-virals and corticosteroids are more effective in Bell’s palsy treatment; many centres currently treat Bell’s palsy with both.

Surgical Referral

Referral to an ENT surgeon should be considered if there is any doubt over the diagnosis, recurrent or bilateral Bell’s palsy, or no sign of improvement after 1 month.

There are surgical options available for patients who have persistent weakness or synkinesis. Synkinesis could be treated with botox injections whilst persistent weakness can be treated with anterior belly of digastric transfer, fascia lata sling, or cross-facial nerve grafting. This will often need referral to a specialist facial plastic surgery service.

A referral to ophthalmology should be made if the cornea remains exposed after attempting to close the eyelid (House Brackmann grade of IV or more).

Complications

85% of cases will recover from Bell’s palsy, the majority of which make a fully recovery with no evidence of residual symptoms.

The factors that suggest a poor prognosis from a facial palsy include:

- Complete palsy

- No signs of recovery within 3 weeks

- Age >60yrs

- Associated pain

- Ramsay Hunt syndrome

- Associated hypertension, diabetes mellitus, or pregnancy

Ramsay-Hunt Syndrome

Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is a Herpes Zoster oticus, whereby there is a unilateral facial palsy caused by reactivation of varicella zoster virus from the geniculate nucleus, the nucelus of the facial nerve.

Clinical Features

It typically initially presents with a moderate to severe ear pain with few other overt clinical signs. Within a few days this will develop into a facial palsy, accompanied by ipsilateral vertigo, hyperacusis, and tinnitus.

Vesicles will be visible during this latter period (Fig. 4), covering the concha, anterior ⅔ tongue, and / or the soft palate.

The facial palsy that develop from Ramsay-Hunt syndrome tend to be more severe than a Bell’s Palsy, with less than 50% making a full recovery with treatment.

Figure 4 – An illustration of the auricular vesicles seen in a case of Ramsay-Hunt syndrome

Investigation and Management

Diagnosis is clinical; virology studies can be requested if necessary but will add little benefit to the overall diagnosis and management

The treatment involves acombination of prednisolone and acyclovir as early as possible. Other complications of Ramsay-Hunt syndrome include chronic tinnitus and vestibular dysfunction.

Key Points

- Facial palsy is weakness or paralysis of the muscles of the face, the most common cause of which is Bell’s Palsy

- Forehead sparing can be used to distinguish between UMN and LMN causes

- Most cases of Bell’s palsy resolve with medical treatment ( i.e. steroids +/-anti-virals)

- Eye care is essential for all patients with facial nerve palsy.

- Ramsay Hunt Syndrome is a Herpes Zoster oticus and has a worse prognosis than Bell’s Palsy