Introduction

Venous thromboembolism (VTE) is a term used to describe both deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) – disorders caused by thrombus formation.

All patients being admitted to the hospital or undergoing surgery should be assessed for VTE risk on admission and re-assessed within 24 hours or if a change occurs in the clinical situation.

VTE is one of theleading causes of preventable death in hospitals and is an important topic for juniors doctors to understand.

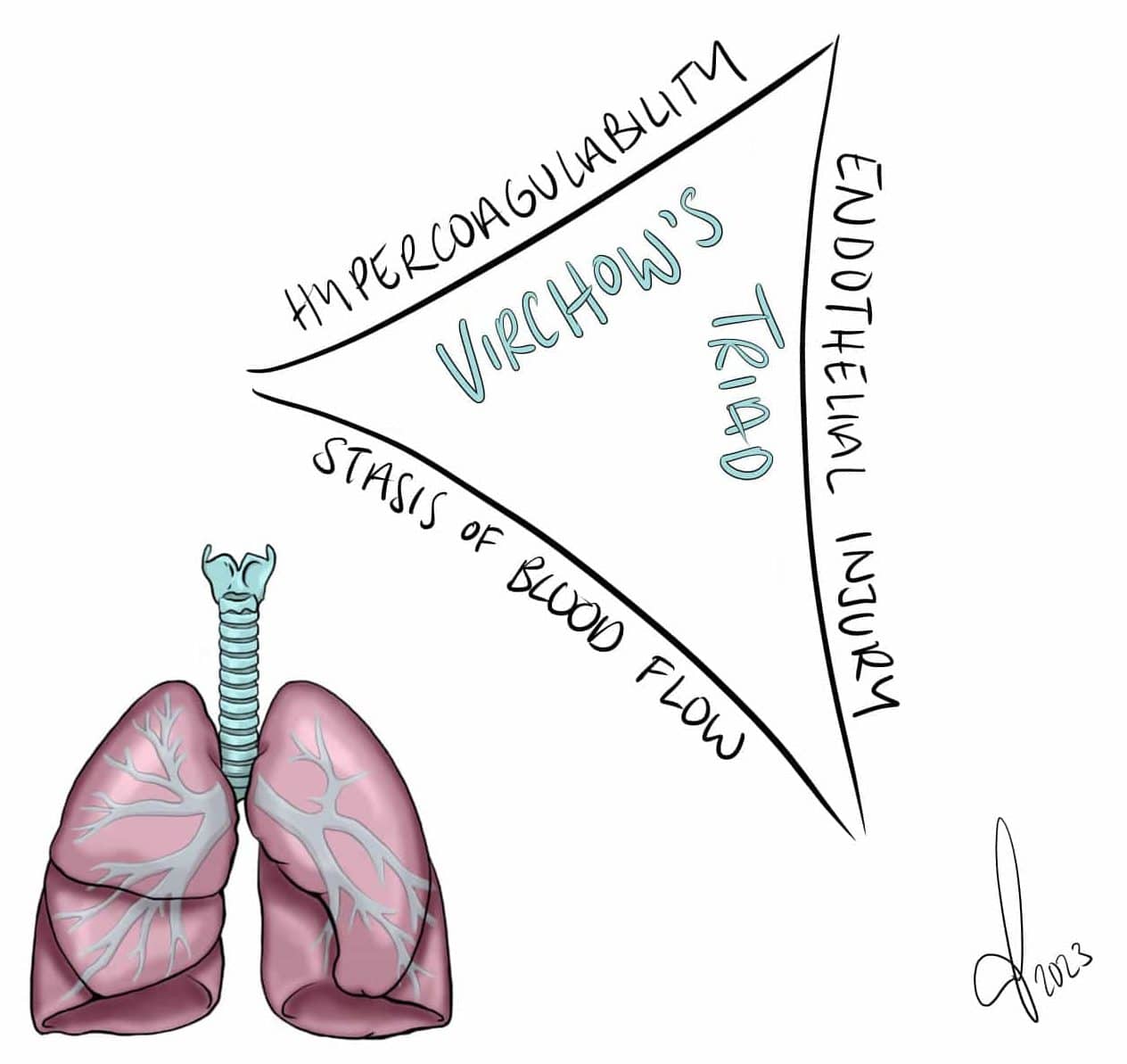

Pathophysiology

The formation of a thrombus in a patient is dependent on any one of Virchow’s Triad (Fig. 1) being present:

- Abnormal blood flow– usually due to recent immobility, such as a long-distance flight or being bed-bound in hospital (this is the most common underlying cause of a DVT)

- Abnormal blood components – can be caused by multiple factors, such as smoking, sepsis, malignancy, or even inherited blood disorders (e.g. Factor V Leiden)

- Abnormal vessel wall – can be from atheroma formation, inflammatory response, or direct trauma

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for developing a venous thromboembolism include:

- Increasing age

- Previous VTE

- Smoking

- Pregnancy or recently post-partum

- Recent surgery (especially abdominal surgery, pelvic surgery, or hip or knee replacements) or prolonged immobility (approx. > 3 days)

- Hormone replacement therapy or combined oral contraceptive pill

- Current active malignancy

- Obesity

- Known thrombophilia disorder (e.g. antiphospholipid syndrome or Factor V Leidin)

Deep Vein Thrombosis

A deep vein thrombosis refers to the formation of a blood clot in the deep veins of a limb, most commonly affecting those of the legs or pelvis.

Clinical Features

The most common presenting symptom of a DVT is unilateral leg pain and swelling (Fig. 2). Other symptoms include low-grade pyrexia, pitting oedema, tenderness, or prominent superficial veins. Importantly, 65% of DVTs are asymptomatic.

Figure 2 – Deep vein thrombosis in the right leg

Investigations

If a deep vein thrombosis is suspected in a patient, the DVT Wells’ Score should be calculated:

- Score less than or equal to 1 – DVT is clinically unlikely, requires a further D-dimer test to exclude

- Score greater than 1 – DVT is clinically likely and a DVT diagnosis should be confirmed via either an ultrasound scan (more common) or a contrast venography (rarely used)

It is important to note that a D-dimer test is sensitive but not specific, specifically a D-dimer may also be raised following recent surgery or trauma, ongoing infection or inflammation, liver disease, or pregnancy.

Investigating for Underlying Causes

Around 10% of DVT patients are subsequently diagnosed with a malignancy. As such, patients should have a thorough history & examination performed, alongside basic blood tests (FBC, U&Es, LFTs, clotting screen). Age-appropriate cancer screening investigations may be required in unprovoked cases, such as CT imaging, to search for an underlying cause.

Management

Direct oral anticoagulants* (DOACs) are now recommended as first line treatment for DVT. Caution is advised in those with chronic renal impairment or if taking potentially interacting medications.

Certain individuals may warrant Vitamin K antagonists (i.e. Warfarin) instead, which needs therapeutic LMWH to cover until the the patients INR levels are sufficiently therapeutic. LMWH alone is recommended in patients with cancer-associated VTE, due to lower recurrence rates than on Warfarin.

Anticoagulation treatment should be continued for 3 months in most patients with a provoked DVT. in those with a proximal DVT and a persistent risk factor or high risk of DVT recurrence may require lifelong anticoagulation

*DOACs include direct factor Xa inhibitors (apixaban, rivaroxaban, and edoxaban) and direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran); whilst dabigatran and edoxaban require initial cover with low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) (>5 days) before commencement of the DOAC, rivaroxaban and apixaban do not

Pulmonary Embolism

A Pulmonary Embolism (PE) refers to a blockage of the pulmonary artery by a substance that has travelled there in the bloodstream.

Most commonly, this blockage is a thrombosis that has migrated. such as from a Deep Vein Thrombosis. Other causes include a right-sided mural thrombus (e.g. post-MI), atrial fibrillation (AF), neoplastic cells, or from fat cells (e.g. following tibial fracture).

Clinical Features

The key clinical features of a PE are sudden onset dyspnoea, pleuritic chest pain, cough, or (rarely) haemoptysis. Clinically, a patient may have tachycardia, tachypnoea, pyrexia, a raised JVP (rare), or pleural rub or pleural effusion (rare). Remember to examine for any signs of DVT in any patient with suspected PE.

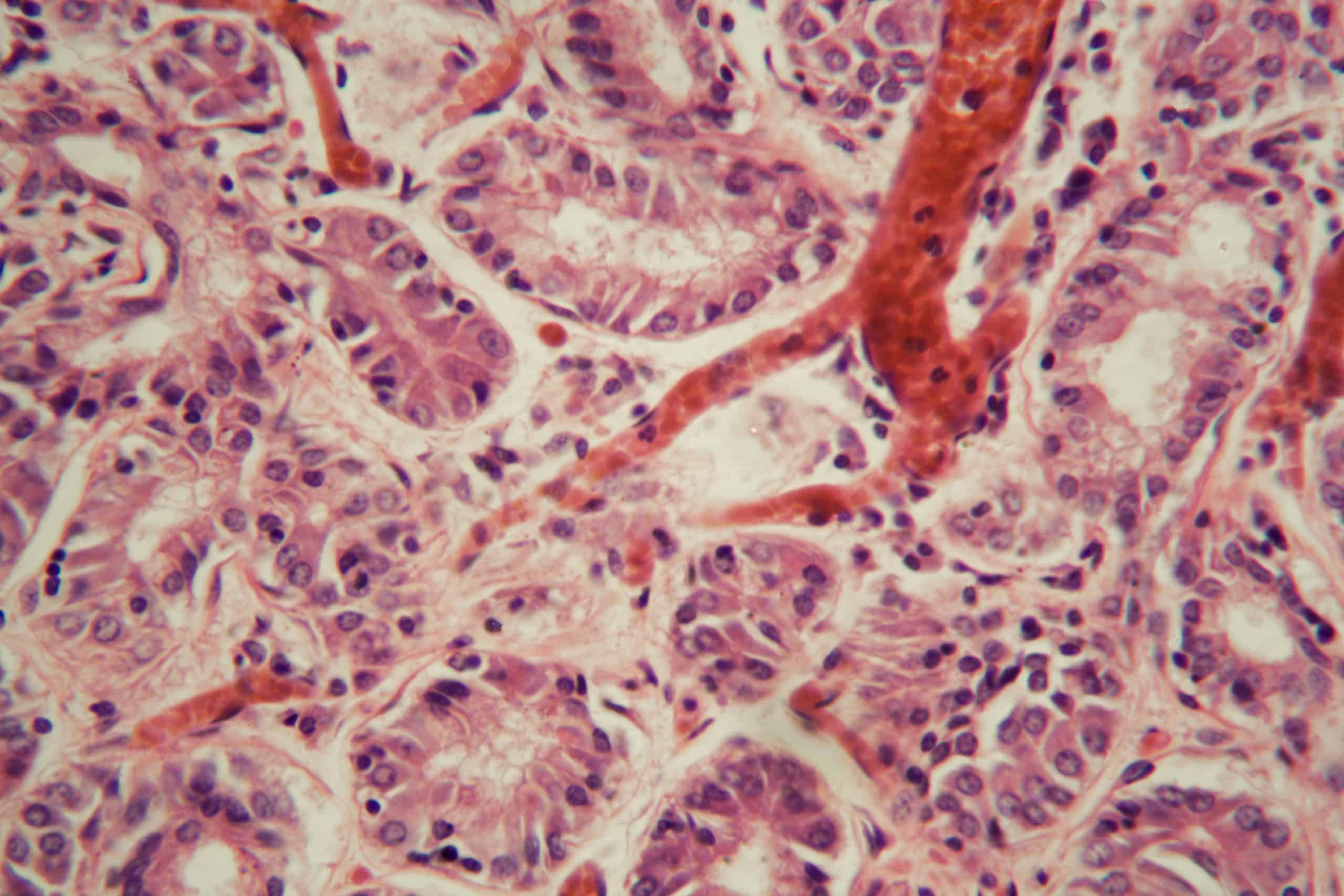

Figure 3 – Microscopic view of micro-embolism within pulmonary vessel

Investigation and Management

If pulmonary embolism is suspected in a patient, the PE Wells’ Score should be calculated:

- Score less than or equal to 4 – PE clinically unlikely, requires a further D-dimer test to exclude*

- Score greater than 4 – PE clinically likely and a PE diagnosis should be confirmed with a CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA) scan (or V/Q scan in those with poor renal function).

As with DVTs, it is important to note that a D-dimer test is sensitive but not specific, specifically a D-dimer may also be raised following recent surgery or trauma, ongoing infection or inflammation, liver disease, or pregnancy.

An ECG should be performed given patients often present with chest pain, however the most common ECG finding in PE is no abnormality or sinus tachycardia*

*Less commonly, a PE may present on ECG with a right bundle branch block (RBBB), RV strain (inverted T waves in V1-V4 and / or leads AvF-III), or a rare S1Q3T3 (deep S wave in Lead I, pathological Q wave in Lead III, and inverted T wave in Lead III)

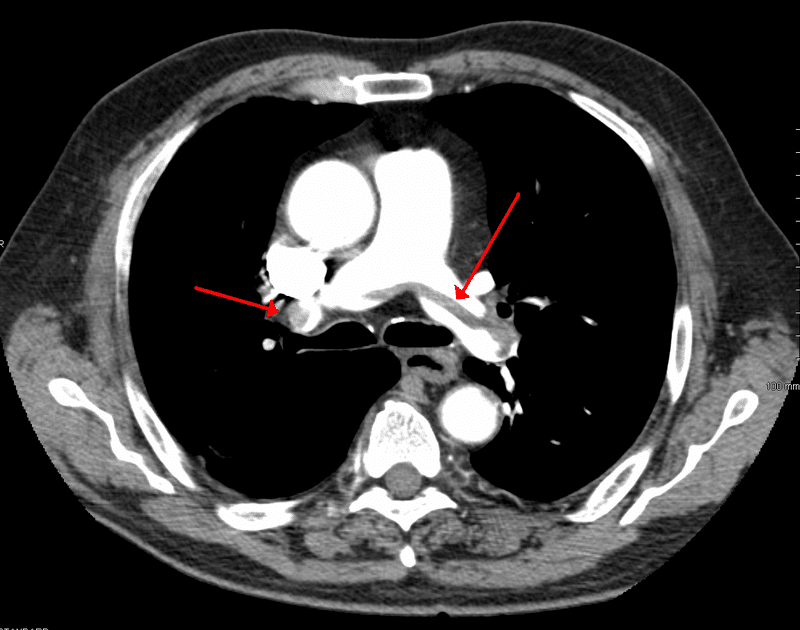

Definitive diagnosis is most often made from a CT Pulmonary Angiography (CTPA) scan (Fig. 4).

Figure 4 – CTPA scan showing a large pulmonary embolism at the bifurcation of the pulmonary artery

For haemodynamically stable PEs, management is much the same as for DVTs, as discussed above.

For those with suspected PEs causing haemodynamic compromise, urgent thrombolysis may be warranted along with input from medical and intensive care teams.

Recurrent PEs known secondary to recurrent DVTs, despite pharmacological management, should be considered for IVC filter.

Thromboprophylaxis

An important part of the management of VTE is prophylaxis. Prophylaxis is typically continued until the patient is no longer considered to be at significant risk of VTE.

All patients undergoing surgery should be offered mechanical prophylaxis unless otherwise contraindicated; mechanical prophylaxis (antiembolic stockings) should not be used in patients with peripheral arterial disease, peripheral oedema, or local skin conditions.

There are two main methods of thromboprophylaxis used in hospital:

Mechanical Thromboprophylaxis

- Antiembolic stockings (AES)

- Intermittent pneumatic compression (IPC, more commonly used in theatre)

Pharmacological Thromboprophylaxis

- Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH), unless poor renal function (eGFR<30) then consider unfractionated heparin (UFH)

For cancer patients undergoing surgery, often they require prolonged period of post-operative prophylaxis (up to 1 month)

Key Points

- Venous thomboembolism (VTE) is a large cause of preventable death

- A VTE risk assessment should be done on all patients

- Patients at risk of VTE should be commenced on appropriate thromboprophylaxis

- Patients with a confirmed VTE require prompt treatment with anticoagulants