Introduction

Inflammation refers to the initial physiological response to tissue damage, such as that caused by mechanical, thermal, electrical, irradiation, chemical, or infective insults.

It can be acute (lasting for a few days) or chronic (in response to an ongoing and unresolved insult). Inflammation can develop into permanent tissue damage or fibrosis.

In this article, we shall look at the processes involved in acute inflammation

Characteristic Features

Acute inflammation begins within seconds to minutes following injury to tissues. It is characterised by four cardinal features (Latin terms in brackets):

- Redness (rubor) – secondary to vasodilatation and increased blood flow

- Heat (calor) – localised increase in temperature, also due to increased blood flow

- Swelling (tumour) – results from increased vessel permeability, allowing fluid loss into the interstitial space

- Pain (dolor) – caused by stimulation of the local nerve endings, from mechanical and chemical mediators

Figure 1 – Redness (rubor) and swelling (tumour), both characteristic features of acute inflammation

Phases of Acute Inflammation

Acute inflammation can be discussed in terms of two stages; (1) the vascular phase, followed by (2) the cellular phase.

Vascular Phase

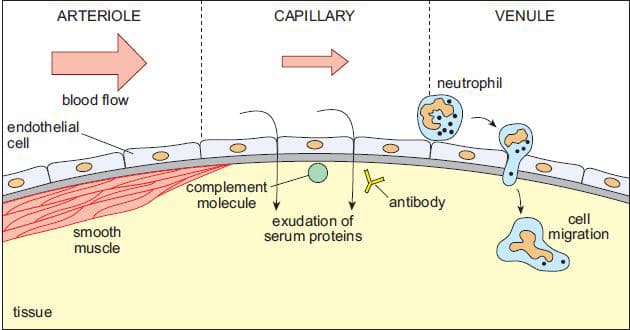

In the vascular phase, small blood vessels adjacent to the injury dilate (vasodilatation) and blood flow to the area increases. The endothelial cells initially swell, then contract to increase the space between them, thereby increasing the permeability of the vascular barrier. This process is regulated by chemical mediators (see Appendix).

Exudation of fluid leads to a net loss of fluid from the vascular space into the interstitial space, resulting in oedema (tumour). The fluid present is termed an “exudate“, and characteristically is high in protein contents due to the increased vascular permeability

The formation of increased tissue fluid acts as a medium for which inflammatory proteins (such as complement and immunoglobulins) can migrate through. It may also help to remove pathogens and cell debris in the area through lymphatic drainage.

Cellular Phase

The predominant cell of acute inflammation is the neutrophil. They are attracted to the site of injury by the presence of chemotaxins, the mediators released into the blood immediately after the insult.

The migration of neutrophils occurs in four stages (Fig. 2):

- Margination – cells line up against the endothelium

- Rolling – close contact with and roll along the endothelium

- Adhesion – connecting to the endothelial wall

- Emigration – cells move through the vessel wall to the affected area

Once in the region, neutrophils recognise the foreign body and begin phagocytosis, the process whereby the pathogen is engulfed and contained with a phagosome. The phagosome is then destroyed via oxygen-independent (e.g. lysozymes) or oxygen-dependent (e.g. free radical formation) mechanisms.

Figure 2 – The stages of acute inflammation; vessel vasodilation, exudate formation, and neutrophil migration

Outcomes

Following the process of acute inflammation, there are several possible results:

- Complete resolution – with total repair and destruction of the insult

- Fibrosis and scar formation – occurs in cases of significant inflammation

- Chronic inflammation – from a persisting insult

- Formation of an abscess

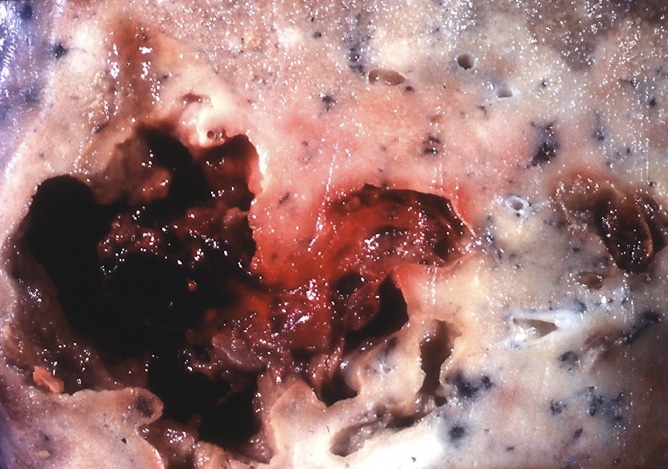

Abscess Formation

An abscess is a localised collection of pus surrounded by granulation tissue. Pus contains necrotic tissue with suspended dead and viable neutrophils and dead pathogens. It forms when the primary insult is a pyogenic bacterium and extensive tissue necrosis occurs.

The initial inflammatory exudate forces the tissue apart, leaving a centre of necrotic tissue with the neutrophils and pathogens. Over time, the acute inflammation will cease and, if not surgically drained, the abscess will be replaced by scar tissue.

An abscess can be a source for systemic dissemination of a pathogen, with the abscess acting as a harbour for the infection. It can also cause continually rising pressures within the tissue, resulting in pain and destruction of local structures.

Figure 3 – Remnant of a drained pulmonary abscess at post-mortem

Key Points

- Inflammation refers to the initial physiological response to tissue damage

- Acute inflammation is characterised by four key features; redness (rubor), heat (calor) swelling (tumour), and pain (dolor)

- The predominant cell of acute inflammation is the neutrophil

- An abscess is a localised collection of pus surrounded by granulation tissue

Appendix – Chemical Mediators

| Mechanism | Mediators |

| Vasodilatation | Histamine, Bradykinin, Complement (C3a, C5a), Leukotrienes (LTC4, LTD4), Prostaglandins (PGI2, PGE2, PGD2, PGF2) |

| Mast cell degranulation | Complement (C3a, C5a) |

| Chemotaxis | Interleukins (IL-8), PAF, Complement (C5a), Histamine |

| Lysosomal granule release | Complement (C5a), Interleukins (IL-8), PAF |

| Phagocytosis | Complement (C3b) |

| Pain | Prostaglandins (PGE2), Bradykinin, Histamine |

| Fever | Interleukins (IL-1, IL-6), TNF-α, Prostaglandins (PGE2) |

Table 1 – Chemical Mediators in Acute Inflammation