Introduction

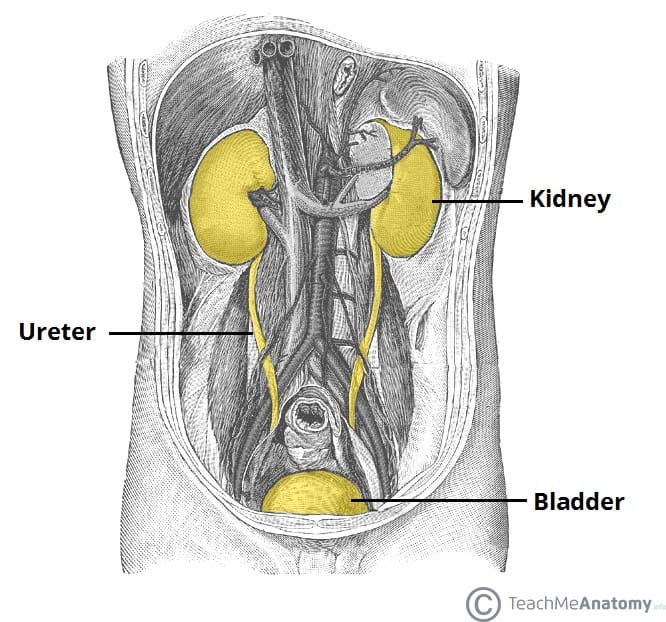

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) is the most common form of adult renal tumour. It is the ninth most common cancer worldwide and constitutes 2-3% of all cancers.

There is a higher incidence in developed countries and RCC is 1.5x more common in men, with a peak incidence 50-70yrs. It accounts for 85% of all renal malignancies, with 1-2% of RCCs bilateral at diagnosis.

Other renal malignancies include transitional cell carcinoma (urothelial tumours), nephroblastoma in children (Wilm’s tumour), and squamous cell carcinomas (chronic inflammation secondary to renal calculi, infection and schistosomiasis).

This article will discuss the presentation, investigation, and management of renal cell carcinomas.

Pathophysiology

RCC is adenocarcinoma of the renal cortex, arising predominantly from the proximal convoluted tubules, most often appearing in the upper pole of the kidney. Microscopically, they are mostly composed of polyhedral clear cells, with dark staining nuclei and cytoplasm rich with lipid and glycogen granules.

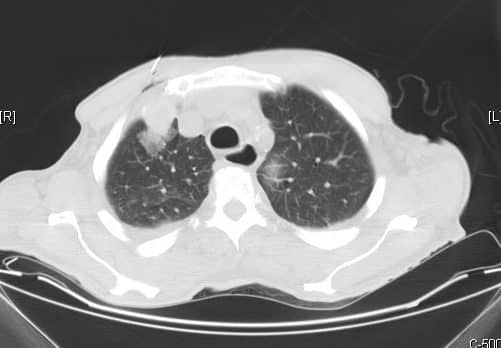

RCCs can spread through direct invasion in to perinephric tissues, adrenal gland, renal vein* or the inferior vena cava. RCC can spread via the lymphatic system to pre-aortic and hilar nodes, or by haematogenous spread to the bones, liver, brain and lung.

*RCCs have a distinct feature by which they can invade through the renal vein wall and into the lumen, a condition termed “tumour thrombosis”

Aetiology

The most common risk factor is smoking, doubling the risk of developing the condition.

Other important risk factors include industrial exposure to carcinogens (such as cadmium, lead, or aromatic hydrocarbons), dialysis (30x increase); hypertension; obesity, and anatomical abnormalities such as polycystic kidneys and horseshoe kidneys.

Certain genetic disorders can also predispose to RCCs, such as von Hippel-Lindau disease (associated with bilateral multifocal toumours), BAP1 mutant disease, and Birt-Hogg-Dube syndrome.

Clinical Features

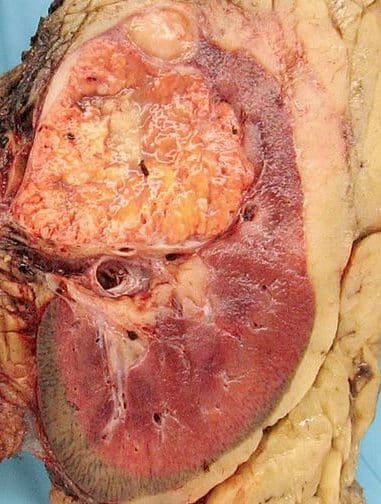

Figure 2 – Macroscopic appearance of a renal cell carcinoma

The most common presenting complaint* for RCCs is haematuria, either visible or non-visible. Patients may also report flank pain, flank mass, or non-specific symptoms, such as lethargy or weight loss.

Around 50% of diagnosed RCCs are detected incidentally on abdominal imaging. The classic triad of haematuria, mass, and flank pain is only present in 15% of cases.

On examination, large RCCs may be able to be palpated in the flank or hypochondrial regions. Left-sided masses may also present with a left varicocoele, due to compression of the left testicular vein as it joins the left renal vein.

Paraneoplastic syndromes caused by ectopic secretion of hormones by RCC can lead to uncommon presentations include polycythaemia due to erythropoetin, hypercalcaemia due to parathyroid hormone, hypertension due to renin, or pyrexia of unknown origin, or with the clinical features of metastasis (such as haemoptysis or pathological fractures)

*As the kidney is a retro-peritoneal organ, RCCs often reach a large size before they can manifest clinically

Differential Diagnosis

Other important differentials of haematuria to be considered include other urological malignancy, renal stones, or urinary tract infection

Investigations

Laboratory tests

Initial routine bloods tests should include full blood count, urea & electrolytes, calcium, liver function tests and C-reactive protein.

Urinalysis should be formed for evidence of non-visible haematuria and urine should be sent for cytology. Currently no serum tumour marker is available to aid in the diagnosis of renal cell carcinoma.

Imaging

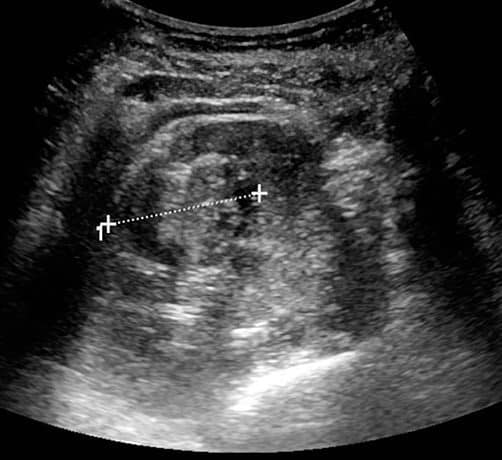

As for most cases of haematuria, initial imaging through ultrasound (Fig. 3) or CT scanning is essential in the work-up of such suspected cases.

However, CT imaging of the abdomen-pelvis pre and post IV contrast is the gold standard for suspected cases, with an additional chest for staging once the condition is confirmed.

There is a role for biopsy of renal lesions, particularly small renal masses when surveillance or minimally invasive ablative therapies are being considered.

Figure 3 – A renal cell carcinoma seen on ultrasound scan of the kidneys

Staging

The American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) staging classification groups patient into 4 stages to provided prognostic information:

| Disease Stage (TNM stage) |

Description |

| Stage 1 (T1N0M0) |

Tumour ≤7 cm and confined to the renal capsule |

| Stage 2 (T2N0M0) |

Tumour >7 cm or invading the renal capsule (but confined to Gerota’s fascia) |

| Stage 3 (T3 or N1M0) |

Tumour extending into the renal vein, vena cava, or spread to 1 local lymph node |

| Stage 4 (T4N2 or M1) |

Tumour extending beyond Gerota’s fascia, >1 local lymph node, involvement of ipsilateral adrenal gland or perinephric fat, or distant metastases |

Table 1 – The American Joint Committee on Cancer Staging Classification for Renal Cell Carcinoma

Management

Localised Disease

The mainstay of treatment for localised disease is through surgical management, either through laparoscopic or open approaches

For smaller tumours, a partial nephrectomy may be suitable; for larger tumours, a radical nephrectomy may be required, to remove the kidney*, perinephric fat, and local lymph nodes en bloc.

For those not suitable or fit enough for surgical management, percutaneous radiofrequency ablation or laparoscopic/percutaneous cryotherapy may be considered. Renal artery embolisation may be required for haemorrhaging disease, prior to any radiofrequency ablation, or for unresectable palliative cases.

Surveillance of slow growing small renal masses can be employed in patients unfit or unwilling to undergo surgery with a limited life expectancy

*The adrenal gland should be spared if possible, except in cases of large upper pole tumours which have a high risk of adrenal invasion

Metastatic Disease

Chemotherapy is considered generally ineffective in patients with RCC.

In otherwise fit patients with metastatic disease, nephrectomy combined with immunotherapy (such as IFN-α or IL-2 agents) is often recommended.

Biological agents that can be used in combination for metastatic disease include Sunitinib (a tyrosine kinase inhibitor) and Pazopanib (also a tyrosine kinase inhibitor)

Metastasectomy (surgical resection of solitary metastases) is recommended where the disease is resectable and the patient is otherwise well.

Prognosis

Approximately 25% have metastasis at presentation. Survival for patients who have undergone nephrectomy is around 70% at 3 years and 60% at 5 years, however those with worse stage disease have a poorer prognosis.

Key Points

- Renal cell carcinoma is the most common form of adult renal tumour

- The most common presenting complaint for RCCs is haematuria, however a large proportion are picked up incidentally on abdominal imaging

- CT imaging of the abdomen-pelvis with IV contrast is the gold standard for diagnosing suspected cases

- The mainstay of treatment for localised disease is through surgical management, with biological agents potentially being used in metastatic disease