Mastitis

Introduction

Mastitis describes inflammation of the breast tissue, both acute or chronic. By far the most common cause is from infection, typically through S. Aureus, but can occasionally be granulomatous.

Mastitis can be classified dependent on lactation status:

- Lactational mastitis (more common) is seen in up to a third of breastfeeding women; it usually presents during the first 3 months of breastfeeding or during weaning

- It is associated with cracked nipples and milk stasis (often caused by poor feeding technique), and is more common with the first child

- Non-lactational mastitis (less common) can occur, especially in women with other conditions such as duct ectasia, as a peri-ductal mastitis

- Tobacco smoking is an important risk factor, causing damage to the sub-areolar duct walls and predisposing to bacterial infection

Clinical Features

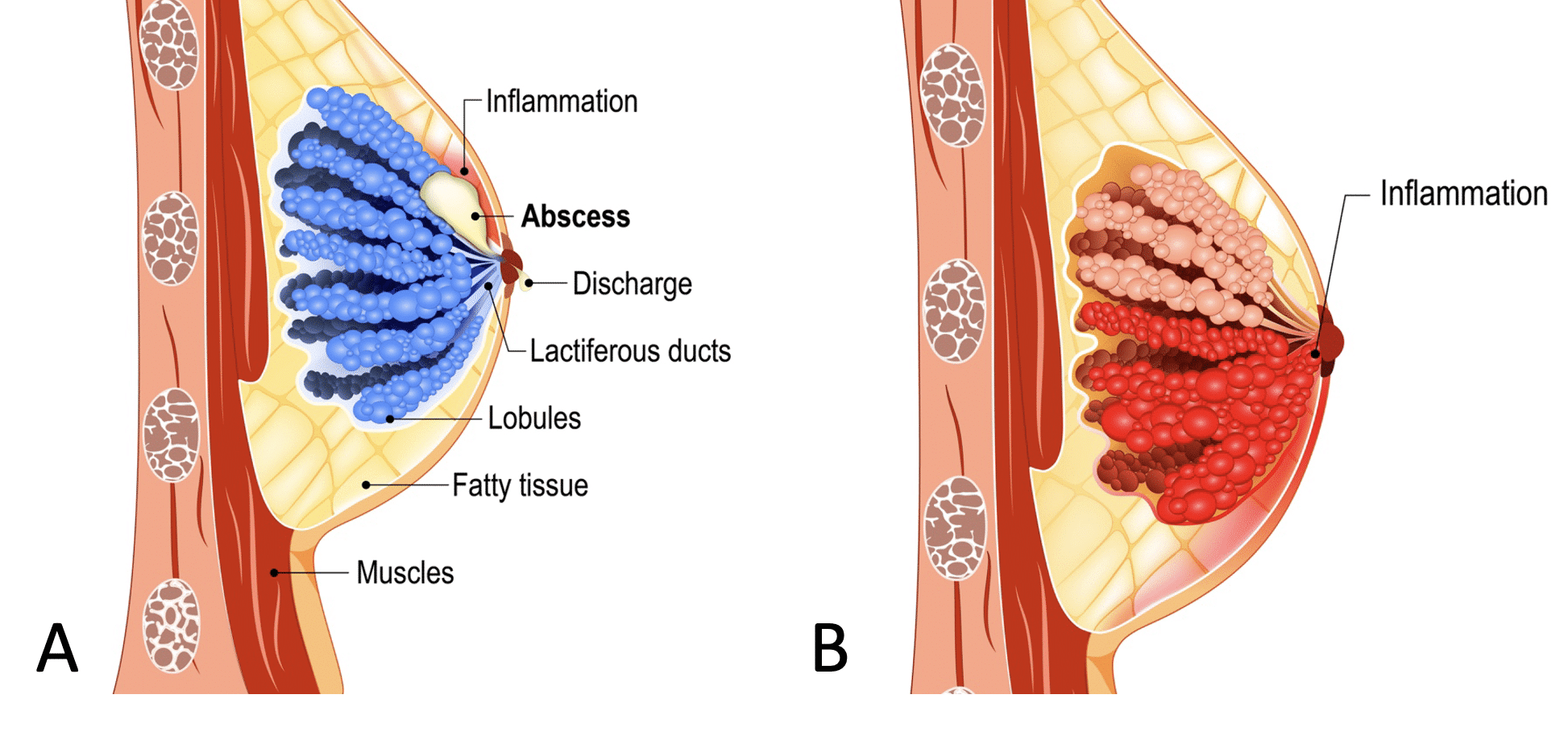

Mastitis presents with tenderness, swelling or induration, and erythema over the area of infection (Fig. 1). Ensure to assess for any developing breast abscess (see below).

Figure 1 – Illustration of difference between (A) breast abscess (B) mastitis

Management

Mastitis is best managed with simple analgesics and a warm compress. For lactational mastitis, continued milk drainage or feeding is recommended.

If symptoms do not improve after 24-48 hours, then antibiotics may be considered . Those which have developed into a breast abscess may require needle aspiration (or less commonly incision and drainage)

Breast Abscess

A breast abscess is a collection of pus within the breast lined with granulation tissue. They most commonly develop secondary to acute mastitis.

They will present with a tender, fluctuant, erythematous mass, often with a punctum present that may or may not be discharging pus. Associated systemic symptoms include fever and lethargy.

A suspected abscess can be confirmed via an ultrasound scan if there is any doubt regarding the diagnosis. Ultrasound-guided needle therapeutic aspiration can be performed, both to help resolution of the abscess and to help guide antibiotic prescribing. More complex abscesses may require incision and drainage under local or general anaesthetic.

An important but rare complication of drainage of a non-lactational abscess is the formation of a mammary duct fistula (a communication between the skin and a subareolar breast duct), which, whilst they can be managed surgically with a fistulectomy and antibiotics, can often recur.

Breast Cysts

Cysts are epithelial lined fluid-filled cavities, which form when lobules become distended due to blockage.

Cysts make up 15% of presentations with palpable breast masses and 7% of women will experience one during their lifetime.

Clinical Features

They can present singularly or with multiple lumps and can affect one or both breasts. On palpation, cysts appear as distinct smooth masses that may also be tender.

Investigations

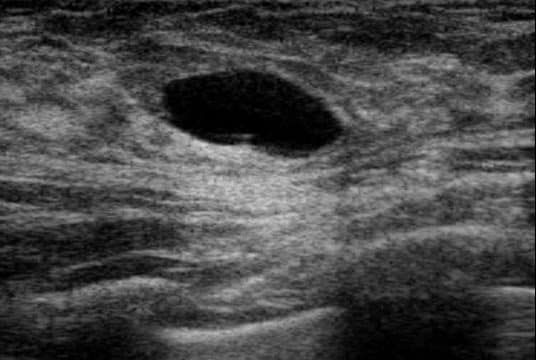

Cysts can be identified by a halo sign on mammography and can usually be definitively diagnosed using ultrasound (Fig. 2).

Persisting, symptomatic, or undeterminable cystic masses may be aspirated, either freehand or using ultrasound. Cancer is less likely if the fluid is free of blood or the lump disappears, otherwise the cystic fluid should be sent for cytology.

Figure 2 – Appearance of a breast cyst on ultrasound

Management

Once diagnosed, cysts usually require no further management and self-resolve, however women are at a higher risk of these recurring. Larger cysts can be aspirated as per patient preference.

Complications

Around 2% patients with cysts have carcinoma at presentation, although most of these are incidental findings not related to the cyst itself.

Some women may develop fibrocystic breast changes caused by multiple small cysts and fibrotic areas. Although benign, it is often associated with tenderness and asymmetry. It can be harder to identify new lumps in these breasts, therefore patient education on regular self examination is vital.

Most patients can be effectively managed with appropriate analgesia and reassurance.

Mammary Duct Ectasia

Duct ectasia is the dilation and shortening of the major lactiferous ducts. It is a common finding in peri-menopausal women, although many women will be asymptomatic.

Clinical Features

Duct ectasia often presents with coloured green/yellow nipple discharge (often bilateral and from multiple ducts), and more rarely a palpable mass, or nipple retraction.

Investigations

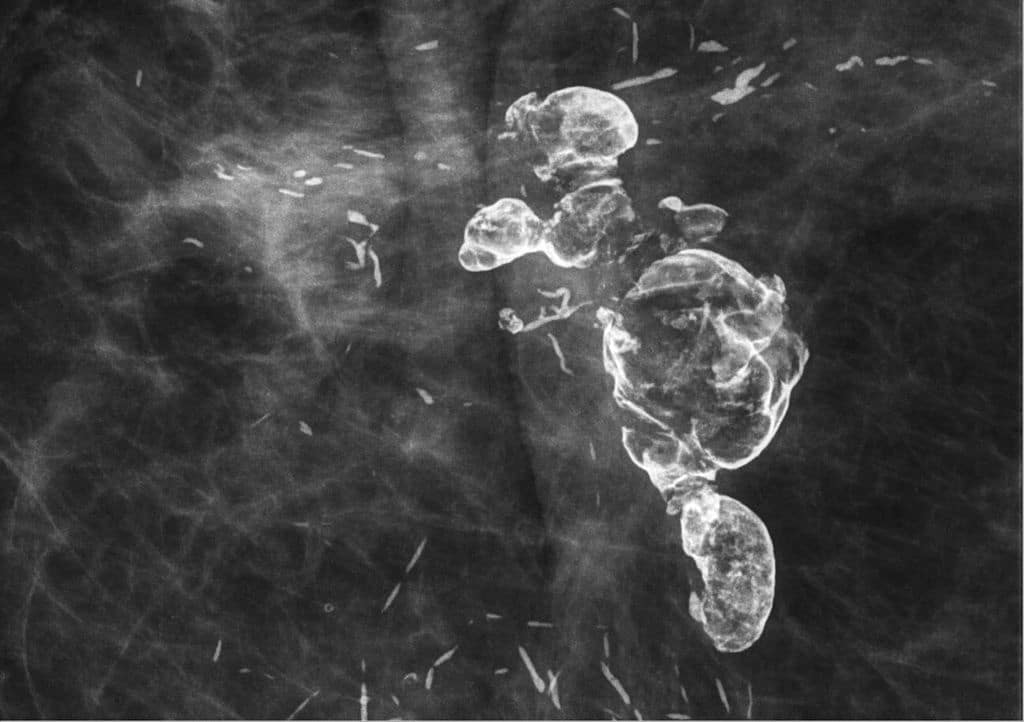

Duct ectasia can be identified by mammography by dilated calcified ducts (Fig. 3), without any other features of malignancy.

If biopsied, the mass typically contains multiple inflammatory cells and secretions on histology.

Figure 3 – Mammary Duct Ectasia, as seen on mammography

Management

This can be managed conservatively, unless radiological findings cannot exclude malignancy. Unremitting nipple discharge can be treated with duct excision.

Fat Necrosis

Fat necrosis is a condition caused by an acute inflammatory response in the breast, leading to ischaemic necrosis of fat lobules.

It is often referred to as traumatic fat necrosis due to its association with trauma, however blunt trauma to the breast is only implicated in 40% cases, with previous surgical or radiological intervention making up the remaining proportion.

Clinical Features

Fat necrosis is usually asymptomatic or presenting as a lump, however less commonly can present with , skin dimpling, pain and nipple inversion.

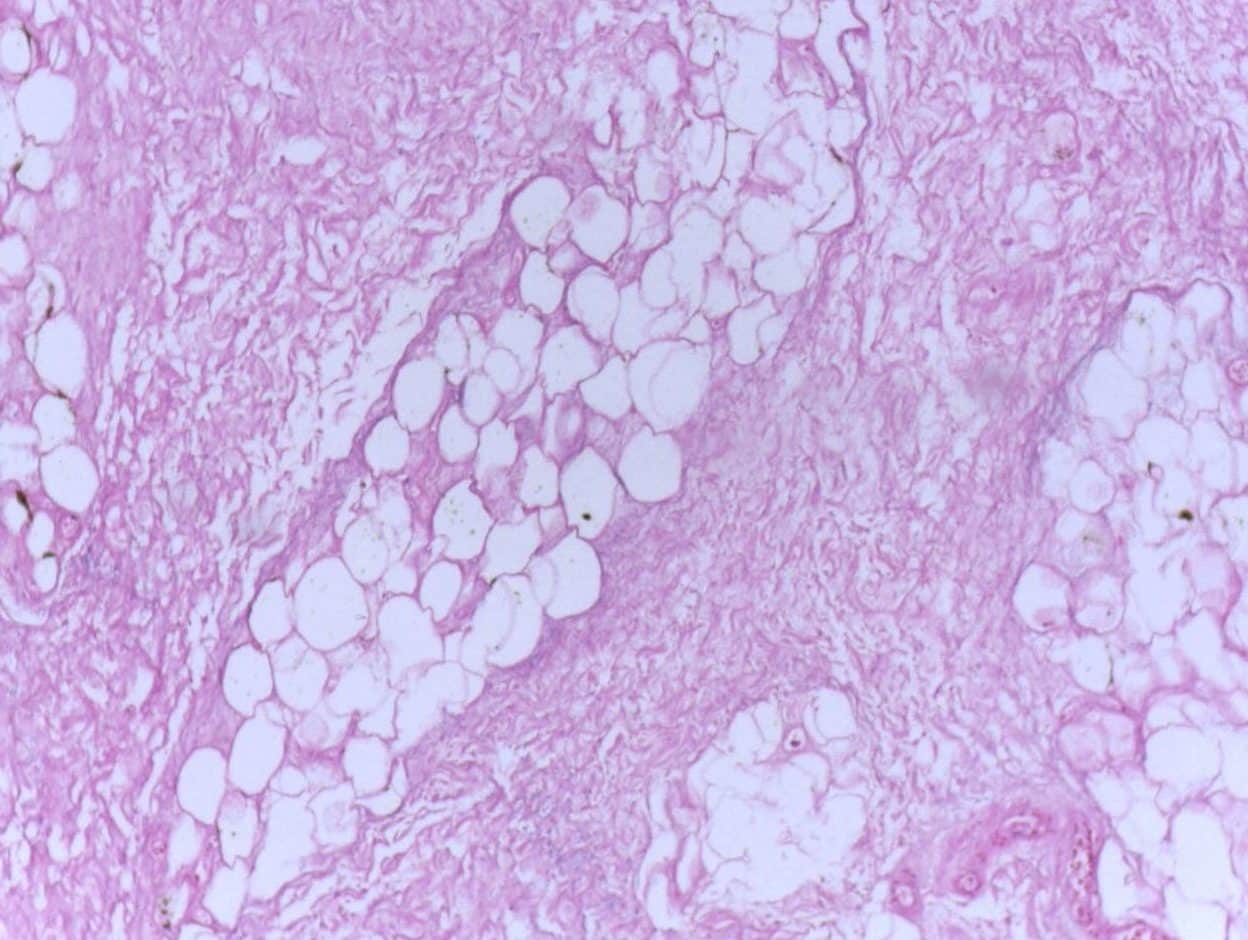

The acute inflammatory response can persist, causing a chronic fibrotic change (Fig. 4) that can subsequently develop into a solid irregular lump.

Figure 4 – Histological appearance of fat necrosis

Investigations

Fat necrosis may be suggested by a positive traumatic history or a benign radiolucent oil cysts on mammography.

More developed fibrotic lesions can mimic carcinoma on mammogram, appearing as calcified irregular speculated masses and the solid irregular lump may feel suspicious on palpation. Therefore a core biopsy is taken if there is clinical suspicion to rule out malignancy.

Management

Fat necrosis is self-limiting and usually only requires analgesic management and reassurance.

Key Points

- Mastitis is inflammation of the breast tissue, much more common in lactating women, and will often need treating with antibiotics

- Breast cysts are epithelial lined fluid filled cavities within the breast tissue and usually requiring no further management and self-resolve

- Duct ectasia often presents with coloured green/yellow nipple discharge, yet is best managed conservatively

- Fat necrosis is ischaemic necrosis of fat lobules, associated with trauma in 40% of cases