Introduction

Sialolithiasis is defined as the presence of calculi in the salivary glands or ducts. Stones will form in the salivary gland or ducts following the stagnation of saliva; they are typically composed of calcium phosphate and hydroxyapatite, as the saliva is rich in calcium

The condition is uncommon, with an incidence of around 2-6 cases per 100000 per year. Whilst most cases are asymptomatic, some can present with facial swelling and / or facial pain.

Sialolithiasis most commonly occur in the submandibular gland (roughly 80-90%), due to the anatomy of this duct being long and its flow of saliva against gravity. The type of salivary secretions from the submandibular gland are also more mucoid in nature as opposed to the more serous secretions from the parotid gland, increasing the risk of sialolithiasis.

Salivary Gland Anatomy

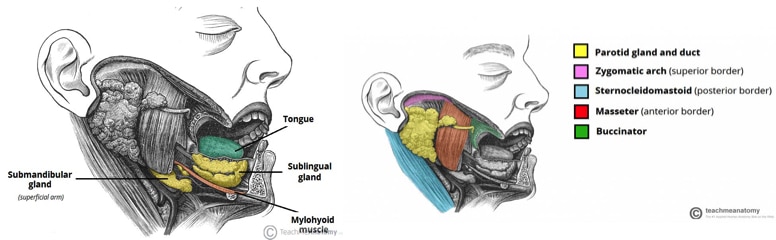

The three major salivary glands (Fig. 1) are:

- Parotid gland – located superior to the angle of the mandible, the gland is superficial to the masseter muscle and drains (via Stensen’s duct) opposite to the upper second molar

- Submandibular gland – lying beneath the floor of the mouth in the submandibular triangle, it drains (via Wharton’s duct) into the floor of the mouth, beside the frenulum of the tongue

- Sublingual gland – located below the mucous membrane of the floor of the mouth, they are drained by multiple small ducts that empty either into Wharton’s duct or directly into the floor of the mouth

Figure 1 – The three major salivary glands, the parotid, submandibular, and sublingual glands

Risk Factors

The main risk factors for developing sialolithiasis include medication (such as diuretics, anti-cholinergics, or antidepressants), dehydration, gout, smoking, periodontal disease, and hyperparathyroidism

Clinical Features

Individuals with sialolithiasis tend to be asymptomatic, however a small proportion can have an intermittent facial swelling and pain, particularly associated with eating. Symptoms are usually unilateral.

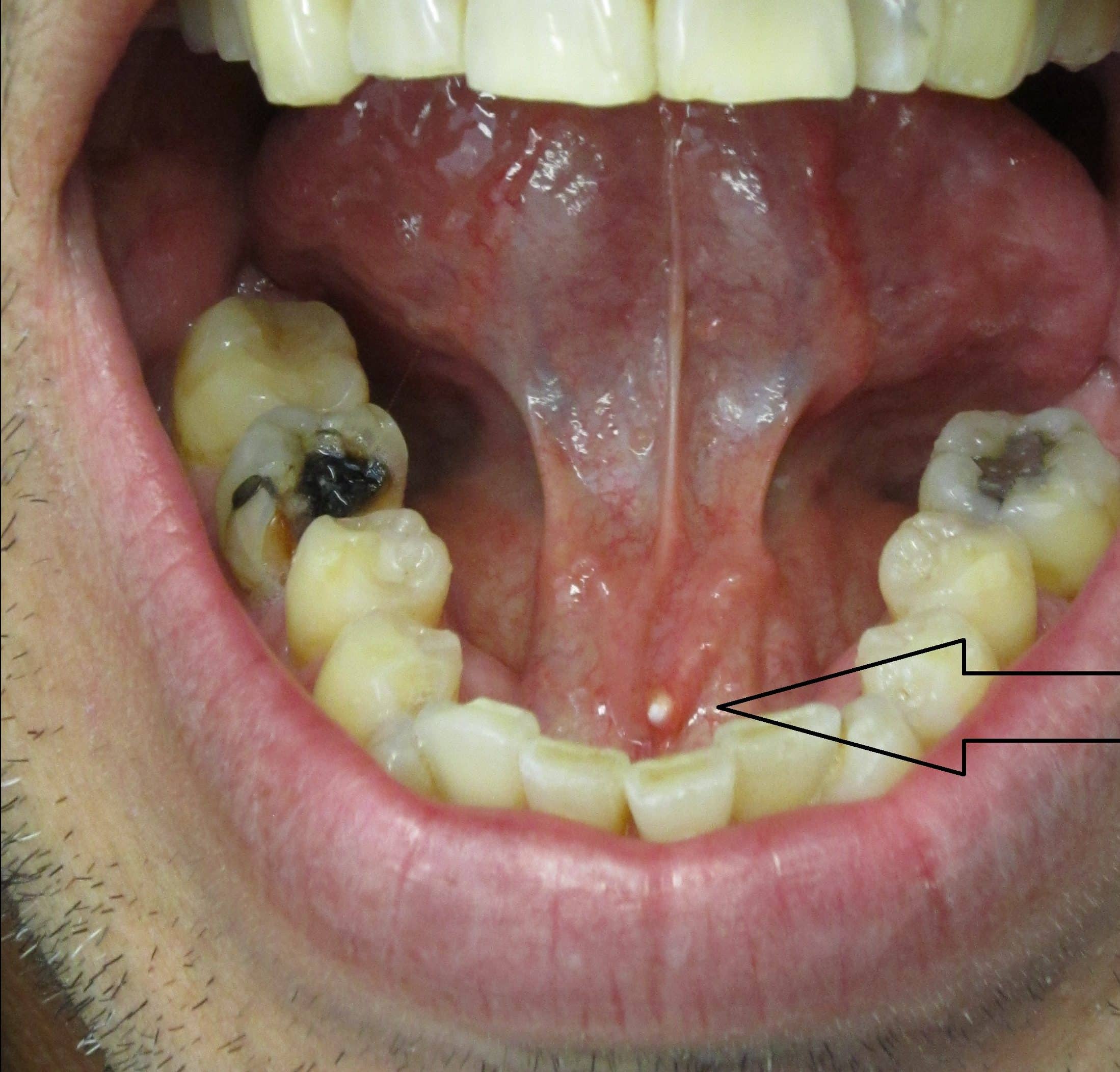

During examination of the oral cavity, bimanual palpation of the salivary ducts should be performed. When the gland is palpated, stones within the duct orifice, alongside saliva, can be observed. When palpated, a stone may be felt in the duct; in the presence of concurrent infection, the gland may also be tender.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential to consider for such a presentation is infection. Individuals with viral infection, such as mumps, will typically present with pain bilaterally, associated with the viral prodrome symptoms such as fever, malaise, and myalgia.

Other differentials to consider include Sjögren’s syndrome, sarcoidosis, or salivary gland tumour.

Investigations

Most cases of suspected sialolithiasis are investigated initially with either ultrasound or plain film radiographs. CT imaging and MRI imaging are rarely used modalities in sialolithiasis.

Ultrasound scans are a minimally-invasive method, which can analyse the whole gland and periglandular structures in good evel of detail. However, small strictures or calculi can be missed.

Plain film radiography can identify the majority of salivary gland stones, however not all stones are radio-opaque (80% submandibular gland, 60% parotid gland) therefore can miss a small proportion of cases.

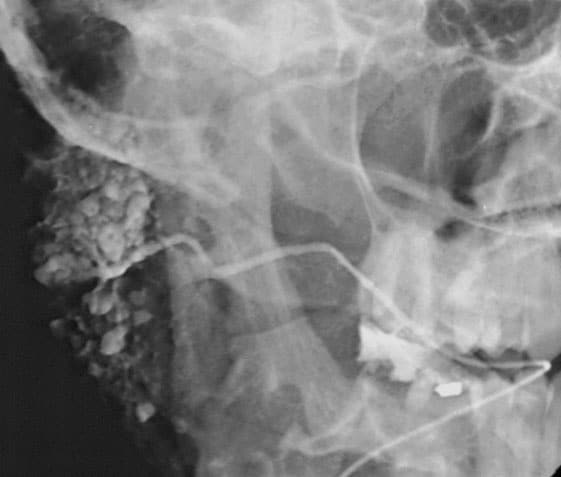

The gold standard investigation is sialography (Fig. 3), whereby the relevant duct is cannulated an injected with radio-opaque dye, following by serial plain film radiographs. Sialography can identify stones and strictures, and smaller stones can also flushed out during the procedure.

Figure 3 – Sialography for a patient with Sjogren’s syndrome

Management

Most patients are managed conservatively with oral hydration, analgesia, and sialogogues, such as lemon juice or sour sweets, which promote saliva production. Milking and massaging of the affected gland can also aid symptoms.

If the gland becomes infected and the patient develops sialadenitis, then antibiotics may be indicated.

Definitive Management

Patients with recurrent or persistent symptoms should be referred for specialist treatment. Interventional radiology procedures are most commonly trialled, which involve fluoroscopic procedures to visualise the stones in the duct, which can then directly extracted.

A surgical approach*can be used to remove some more difficult stones; a transoral approach can be used if the stones are distal or a transcervical approach for more proximal stones (or where the transoral approach has been unsuccessful).

Sialoendoscopy is usually reserved for stones <5mm, whereby the stones are directly visualised via endoscopic imaging and extracted with a basket, or extracorporeal shockwave lithotripsy, which is reserved for stones in the proximal duct, where transoral retrieval of the stone is not possible.

Salivary gland excision (most commonly submandibular gland excision) will be considered for patients with persisting symptoms which have failed conservative or medical management, or if they have a large intraglandular calculus.

*Surgical intervention has associated risks of damage to the hypoglossal, facial, or lingual nerves

Complications

Most patients with salivary calculi will live with them for several years, however can develop recurrent infections leading to chronic sialadenitis.

Key Points

- Sialolithiasis is the presence of calculi in the salivary glands or ducts

- Most cases are asymptomatic yet some may present with unilateral face swelling, typically worse with eating

- Most cases of suspected sialolithiasis are investigated with either ultrasound or radiographs, however the gold standard is a sialogram

- Conservative management is all that is required for most cases, however surgical and radiological interventions may be required in a small proportion