Introduction

Melena refers to black tarry stools, which usually occurs as a result of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

It has a characteristic tarry colour and offensive smell, and is often difficult to flush away. The change to the stool consistency occurs due to the alteration and degradation of blood by intestinal enzymes, resulting in melena.

In this article, we shall look at the differential diagnosis, clinical features and investigations for melena.

Differential Diagnosis

Melena usually occurs as a result of an upper gastrointestinal bleed, however can also occur from bleeding occurring in the small bowel (albeit rare)

There are a number of causes for upper GI bleeding, however the most common are peptic ulcer disease, variceal bleeding, and malignancy.

Peptic Ulcer Disease

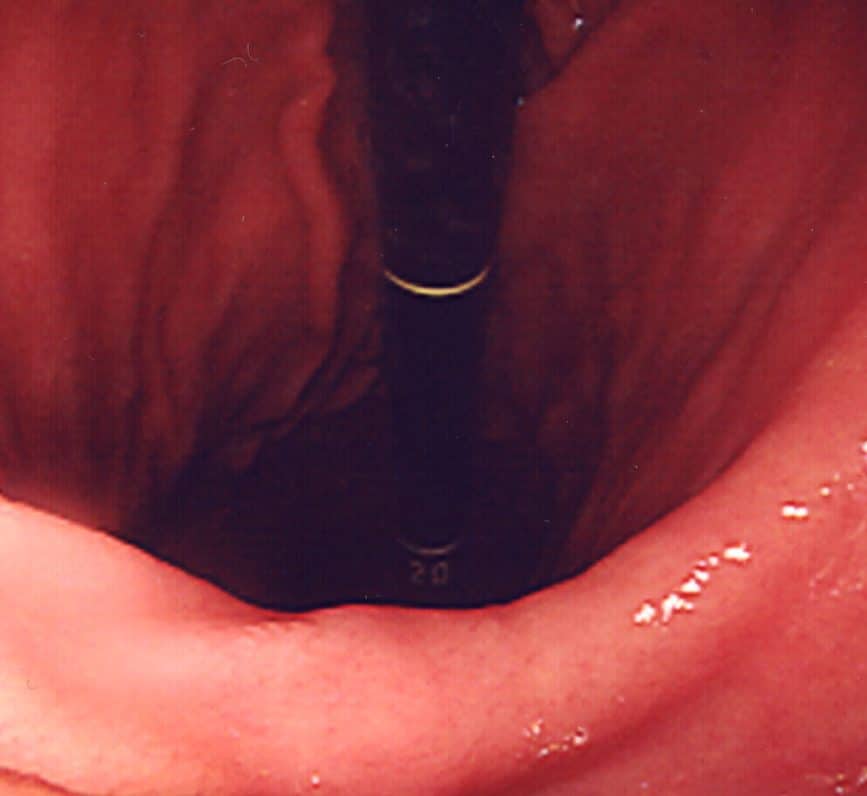

Peptic ulcer disease is the most common cause of melena (Fig. 1). Whilst it can affect any patient group, it should be especially suspected in those with known active peptic ulcer disease, a recent history of NSAID use or steroid use, or known H. pylori infection

Classically, the most significant bleeding will occur if an ulcer erodes through the posterior gastric wall into the gastroduodenal artery. However, in reality, extensive bleeding can occur with the erosion of any blood vessel.

Figure 1 – Endoscopic image of a bleeding gastric ulcer

Variceal Bleeds

Oesophageal varices refer to dilations of the porto-systemic anastomoses in the oesophagus. They most commonly occur due to portal hypertension secondary to liver cirrhosis and are prone to rupture.

The most common underlying cause for oesophageal varices is alcoholic-related liver disease (ArLD), however can occur with any patient with chronic liver disease. Any melena occurring in a patient with a known chronic liver disease should be urgently investigated for potential variceal bleeding.

Upper GI Malignancy

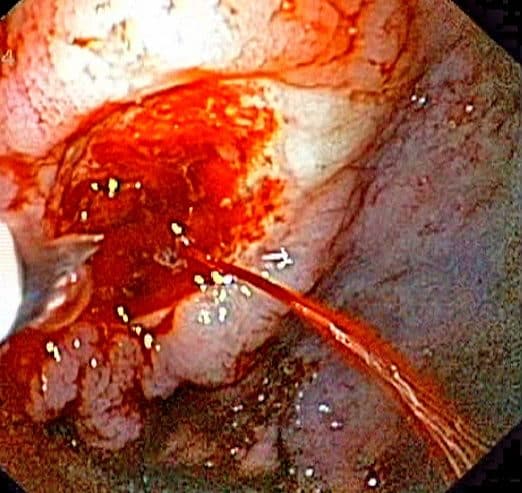

Ulcerating oesophageal or gastric malignancies (Fig. 2) can first present with melena, causing a gradual flow of blood that may present prior to any other cancer-associated symptoms.

In the assessment of any patient with melena, it is important to enquire about dysphagia, dyspepsia, weight loss, and relevant family history, potentially suggestive a diagnosis of malignancy.

Figure 2 – A gastric malignancy, first presenting as melena

Other Causes

Other less common causes of melena include gastritis or oesophagitis, Meckel’s diverticulum, small bowel tumours, or vascular malformations (e.g. angiodysplasia).

Clinical Features

The key facts to ascertain from a patient presenting with melena are:

- Colour and texture of the stool – best described as a jet black, tar-like, and sticky

- Associated symptoms – including any haematemesis, abdominal pain, weight loss, dyspepsia, or dysphagia

- Past medical history – including smoking and alcohol status

- Drug history – use of steroids, NSAIDs, anticoagulants, or iron tablets*

A digital rectal examination is essential to confirm the melena. A full abdominal examination must be performed, importantly to assess for peritonism, hepatomegaly, or stigmata of liver disease.

*Patients on iron tablets will have black stool, so ensure to clarify the temporal sequence for any symptoms with the starting of iron tablets

Investigations

Initial Investigations

All patients with suspected melena should undergo routine blood tests, including FBC, U&Es, LFTs, and clotting, to help investigate for underlying causes and to stratify overall risk.

Any drop in haemoglobin and rise in the urea:creatinine ratio is very indicative of an upper GI bleed, as digested haemoglobin produces urea as a by-product and is readily absorbed by the intestine

Ensure all patients with melena have a Group and Save performed, with those with any significant haemoglobin drop or haemodynamic instability having blood products cross-matched too.

Further Investigations

All patients with new onset melena must undergo a gastroscopy (OGD) for further assessment. This will not only potentially identify the cause of melena, but also can allow for definitive interventions in certain cases (e.g. banding of varices)

The urgency by which an OGD is performed should be determined by the patients Glasgow-Blatchford bleeding score (GBS), used to risk stratify patients based purely on clinical and biochemical parameters.

However, in certain cases, OGD may be inconclusive and therefore in those with ongoing melena, further investigations are required:

- CT angiogram can be useful in assessing for any active bleeding, especially in those with suspected ongoing bleeding and / or haemodynamic compromise

- Colonoscopy should be performed, especially those who are haemodynamically stable, to ensure that the cause of the melena is not actually proximal colonic in origin (e.g. a caecal tumour)

In the rare scenario that the above investigations are all normal, capsule endoscopy or RBC Scintigraphy may be considered for further investigations.

Management

In any critically unwell patient, an A to E approach should be used to stabilise the patient prior to any definitive management steps.

Blood products should be transfused to those who are haemodynamically unstable (urgently) or with a low haemoglobin. Any deranged coagulation should be corrected as appropriate, which may include use of fresh frozen plasma (FFP) +/- platelets, especially for those with impaired liver function.

The underlying cause identified will determine the necessary management option:

- Peptic ulcer disease – requires injections of adrenaline and cauterisation of the bleeding during endoscopy; patients should then be commenced on high dose intravenous proton pump inhibitor (PPI) therapy to reduce gastric acid secretion

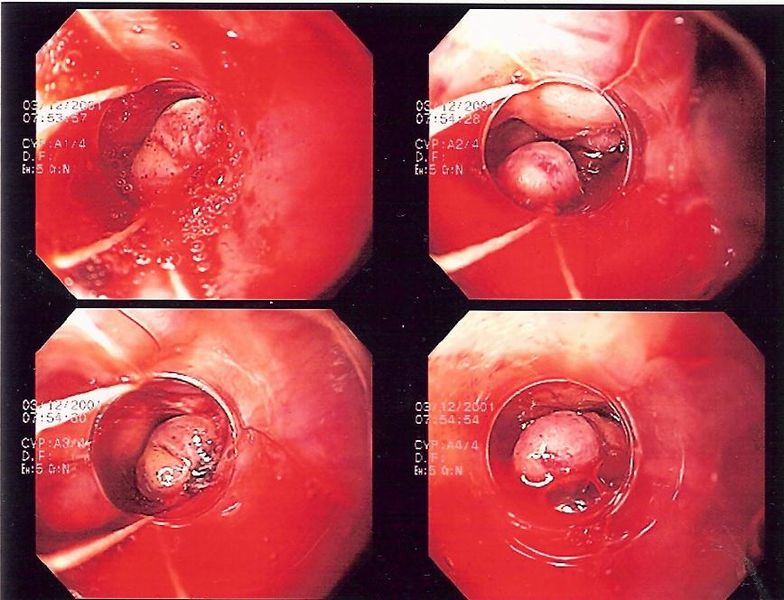

- Oesophageal varices – needs urgent endoscopy and concurrent resuscitation with blood products, alongside prophylactic antibiotics and somatostatin analogues (e.g. terlipressin or octreotide, to reduce splanchnic blood flow) to be given

- Endoscopic banding is the most definitive method of management but can be technically difficult (Fig. 4); a Sengstaken-Blakemore tube can be used in severe or uncontrollable cases as a temporary control to compress the bleeding

- Upper GI malignancies – will require biopsies to be taken and a definitive surgical and oncological management plan is required

Figure 4 – Endoscopic banding of bleeding oesophageal varices

Key Points

- Peptic ulcer disease, oesophageal varices, and malignancy are the most common causes of melena

- Urgent resuscitation is the mainstay of initial treatment for any cases of melena

- Definitive investigation in most cases of melena is via gastroscopy, however further investigations may be required if normal