Introduction

The spleen is an extremely vascular organ and consequently splenic rupture can lead to large intraperitoneal haemorrhage, rapidly leading to fatal haemorrhagic shock.

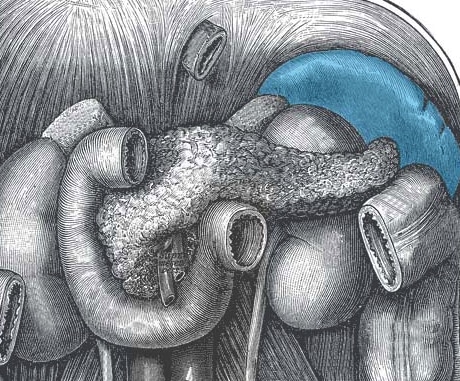

Whilst protected by the ribcage (Fig. 1), the majority of cases of splenic injury are secondary to abdominal trauma – particularly blunt trauma. Common situations in which the spleen is injured include seat-belt injuries in road traffic collisions and falls onto the left side (such as patients slipping on ice or elderly patient falling in the bathroom).

A minority of cases are iatrogenic, or secondary due to underlying splenomegaly from haematological malignancy or infective causes (such as Epstein-Barr virus). In these cases, as the spleen grows, the capsule stretches and thins, becoming more fragile and predisposing to rupture.

Clinical Features

Diagnosis is most commonly made from the investigations of abdominal pain following a history of trauma.

Patients may complain of abdominal pain, however a proportion will only present with the clinical features of hypovolaemic shock. Only work-up imaging will confirm the diagnosis.

On examination, patients may have left upper quadrant tenderness and / or peritonism (often becoming more generalised as the blood loss increases). Free blood can irritate the diaphragm and cause a radiating left shoulder pain (known as Kehr’s sign).

Investigations

Patients who are haemodynamically unstable with peritonism following trauma have abdominal bleeding until proven otherwise and require immediate laparotomy.

Those who are haemodynamically stable with suspected abdominal injury will need an urgent CT chest-abdomen-pelvis with intravenous contrast (Fig. 2)

CT imaging allows for the identification and assessment of splenic injury*, alongside any other abdominal viscera involvement. Specifically, it also allows for the grading of the splenic injury to guide further management.

*FAST scans in the emergency department setting can reveal free peritoneal fluid or fluid in the pericardium, however whilst a potentially helpful adjunct, they should not delay CT imaging and / or surgical intervention

Figure 2 – A traumatic splenic rupture as seen on CT scan, the rim at the lower edge demonstrating a sign of free fluid (blood)

Organ Injury Scale

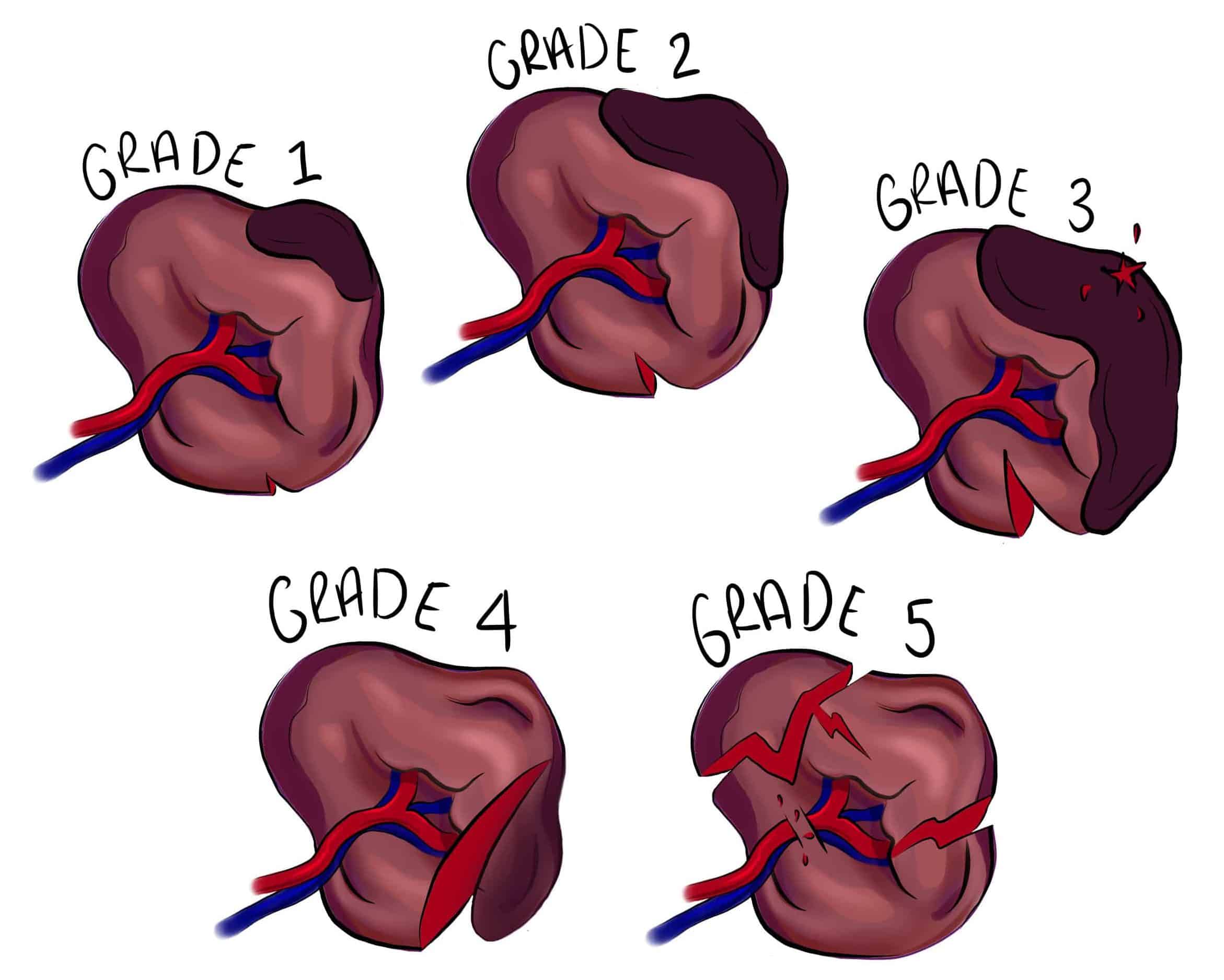

The American Association for the Surgery of Trauma (AAST) splenic injury scale (Table 1) is the most commonly used system for grading splenic trauma. It is used to help guide which patients are likely to benefit from conservative management and which need surgery.

|

Grade of Injury |

Description |

|

1 |

– Capsular tear <1cm parenchymal depth – Subcapsular haematoma <10% surface area |

|

2 |

– Capsular tear 1-3cm parenchymal depth – Subcapsular 10-50% surface area, or intraparenchymal <5cm |

|

3 |

– Capsular tear >3cm parenchymal depth, or any tear involving trabecular vessels – Subcapsular >50% surface area, or intraparenchymal >5cm, or any expanding or ruptured haematoma. |

|

4 |

– Laceration involving segmental or hilar vessels, devascularising >25% of the spleen |

|

5 |

– Completely shattered spleen or hilar vascular injury, devascularising the entire spleen |

Table 1 – The AAST Splenic Injury Scale

Management

All patients with suspect splenic injury should be assessed, resuscitated, and treated according to ATLS principles. Patients who are haemodynamically unstable* or with a grade 5 injury (a shattered spleen or major hilar vascular injury) need urgent laparotomy and splenectomy.

Haemodynamically stable patients with grade 1–3 injuries without active extravasation can be considered for conservative treatment. They should be resuscitated using the principle of permissive hypotension, admitted to a high dependency area for observation, and have serial abdominal examinations for any evidence of deterioration, with a low threshold for repeat imaging

Consideration should be given for prophylactic vaccinations (against Strep Pneumoniae, Haemophilus Influenzae B (HIB) and Meningococcus) and prophylactic antibiotics (against encapsulated bacteria)

Splenic Artery Embolisation

Splenic artery embolisation by interventional radiology is an important alternative management option, where available, potentially negating the need for laparotomy and preserving splenic function. This should be used haemodynamically stable with high grade splenic injuries.

For multifocal injuries, a proximal embolisation involving the splenic artery can be used, whilst in more focal bleeding, a targeted distal embolisation can be performed, Proximal embolisation can also be used alongside surgery in high grade injuries to facilitate splenic salvage surgery.

Embolic agents that are used for splenic embolisation include metallic coils, glue, gelfoam, or particles. Even when a vessel is embolised, there is a small proportion who fail this approach and will require a splenectomy.

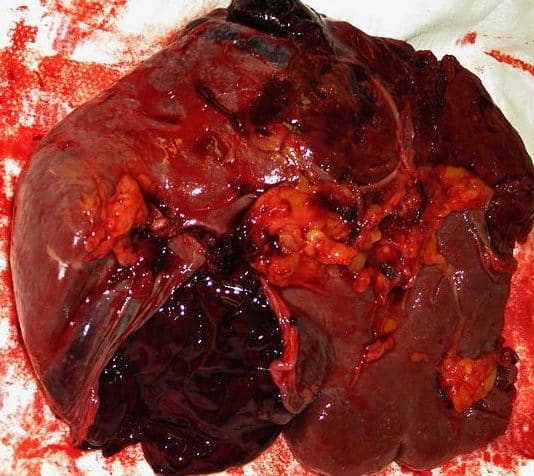

Figure 4 – A ruptured spleen, following a laparotomy with splenectomy

Complications of Treatment

The main complications of conservative treatment or embolisation are ongoing bleeding, splenic necrosis, splenic abscess or cyst formation, and thrombocytosis* (typically transient)

The main complications following splenectomy include intra-abdominal collections, thrombocytosis* (typically transient), and Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection.

The overall mortality rates of patients presenting to hospital with trauma splenic injury are around 10%.

*There is a theoretical increased thrombotic risk, including deep vein thrombosis and portal vein thrombosis, with increasing platelet count, however advice from a haematologist for ongoing management (e.g. aspirin therapy) should be taken if the platelet count rises above 1000 x109/L

Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection

The spleen is an immunologically active organ, with an active role in destroying encapsulated organisms, such as Pneumococcus, Meningococcus, and H. Influenzae.

Asplenic patients are therefore unable to mount a normal immunological response against these organisms and infection can lead to overwhelming sepsis, termed Overwhelming Post-Splenectomy Infection (OPSI)

Consequently, any asplenic patient, including those post-splenectomy, should receive vaccinations against these three organisms. In addition, prophylactic Penicillin V should be considered (this may not be required lifelong in low-risk patients).

Key Points

- Any patient with a history of collapse or trauma with left-sided abdominal pain should be considered to have a splenic rupture until proven otherwise

- Patients who are haemodynamically unstable with peritonism have abdominal bleeding until proven otherwise and require immediate laparotomy

- Patients who are not haemodynamically unstable with suspected abdominal or chest injuries need an urgent CT chest / abdomen / pelvis with IV contrast

- All patients should be assessed, resuscitated and treated according to ATLS principles

- Patients who are haemodynamically unstable or with a grade 5 injury (a shattered spleen or major hilar vascular injury) need urgent laparotomy