Fluid management is a major part of junior doctor prescribing; whether working on a surgical firm with a patient who is nil-by-mouth or with a dehydrated patient on a care of the elderly firm, this is a topic that a junior doctor utilises on a regular basis.

Ensuring considered fluid and haemodynamic management is central to peri-operative patient care and has been shown to have a significant impact on post-operative morbidity and the length of hospital stay. Hence it is essential to gain a firm understanding of the physiology of fluid balance and the compositions of each fluid being prescribed.

*Please be aware that this article talks solely about adult fluids and does not cover paediatric prescribing.

Introduction

Firstly it’s important to think about why fluids should be prescribed in the first place. The reasons for fluid prescription are:

- Resuscitation

- Maintenance

- Replacement

The relative importance of each of these varies between patients. Perhaps the most important point to remember therefore is that correct fluid prescription varies depending on the individual patient and it is essential to take individual patient characteristics into account before prescribing fluid.

The general key considerations to remember with every patient are:

- Is the aim of the fluid for resuscitation, maintenance, or replacement?

- What is the weight and size of the patient?

- The fluid requirements of a frail 45kg 80yr female and a healthy 100kg 40yr male will be significantly different

- Are there any co-morbidities present that are important to consider, such as heart failure or chronic kidney disease?

- What is their underlying reason for admission*?

- What were their most recent electrolytes?

*After some operations, patients are deliberately run “on the dry side”, whilst septic patients or patients in bowel obstruction will need aggressive fluid prescribing.

Fluid Compartments

Around 2/3rd of total body weight is water (‘total body water’). Around 2/3 of this distributes in to the intracellular fluid and the remaining 1/3 will distribute in to the extracellular fluid.

Of that fluid in the extracellular space, around 1/5th stays in the intravascular space and 4/5th of this is found in the interstitium, with a small proportion in the transcellular space.

For the general maintenance of hydration, it is necessary for fluid to distribute into all compartments. However, if the aim is to fluid resuscitate a patient (improving tissue perfusion by raising the intravascular volume), it is more important these fluids stay within the intravascular space. This concept will help us understand why different fluids are available and for what purpose they might be used.

The Septic Patient

In patients who are septic, the tight junctions between the capillary endothelial cells break down and vascular permeability increases. As a result, increasing hydrostatic pressures and reducing oncotic pressure lead to fluid leaving the vasculature and entering the tissue.

It is often therefore necessary to give relatively large volumes of intravenous fluid to maintain the intra-vascular volume, even though the total body water may be high. Close monitoring of the fluid balance will be required.

Fluid Input-Output

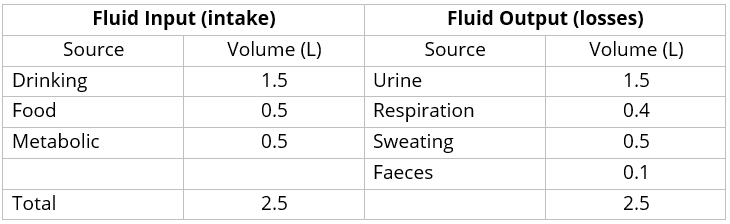

The proportions of fluid that are gained and lost from various sources are shown in Table 1.

Note that these figures are the average for a 70kg man. The actual amount varies considerably depending on physiological status and body weight (which in adult patients can vary from around 40kg to 200kg).

Fluid Input

Only 3/5th of our fluid input comes through fluids via the enteric route, with the remainder from both food and metabolic processes. Hence, when a patient is nil by mouth (NBM), it is important that all sources are replaced via the parenteral route.

Fluid Output

Losses from non-urine sources are termed insensible losses; insensible losses will rise in unwell patients, who may be febrile, tachypnoeic, or having increased bowel output. These factors should be taken into account when deciding how much fluid a patients needs replacing.

When patients start to clinically improve, their vascular permeability returns to baseline state. They therefore often “correct themselves” and urinate out the excess fluid that was previously required to maintain their intravascular volume and tissue perfusion. In such patent, monitor the electrolytes and allow this correction to occur, as this is normal and is to be expected (rarely will supplementary IV fluids will be warranted in such cases).

Assessment of Fluid Status

It is essential to utilise various clinical parameters to continually assess the patient’s fluid status. A doctor’s first assessment is, of course, the patient’s clinical status.

In the fluid depleted patients, one should be looking for:

- Dry mucous membranes and reduced skin turgor

- Decreasing urine output (should target >0.5 ml/kg/hr)

- Orthostatic hypotension

- In worsening stages:

- Increased capillary refill time

- Tachycardia

- Low blood pressure

In patients who may be fluid overloaded, one should be looking for:

- Raised JVP

- Peripheral or sacral oedema

- Pulmonary oedema

Ensure that the patient has a fluid input-output chart and daily weight chart commenced; you will need to ask the nurses to begin one of these (despite commonly being poorly maintained). Also ensure to monitor the patient’s urea and electrolytes (U&Es) regularly, for any evidence of dehydration, renal hypoperfusion, or electrolyte abnormalities.

Daily Requirements

Patients do not just require water, they also need Na+, K+, and glucose replacing too, particularly if they are nil by mouth. You will find numerous ways of calculating the daily requirements of these 4 components and they are invariably based on the patient’s weight.

Current NICE guidelines suggest the following:

- Water: 25 mL/kg/day

- Na+: 1.0 mmol/kg/day

- K+: 1.0 mmol/kg/day

- Glucose: 50g/day

Based on these required, it is necessary to consider the fluids that are available for prescription and what exactly they contain, to be able to prescribe appropriately

Intravenous Fluids

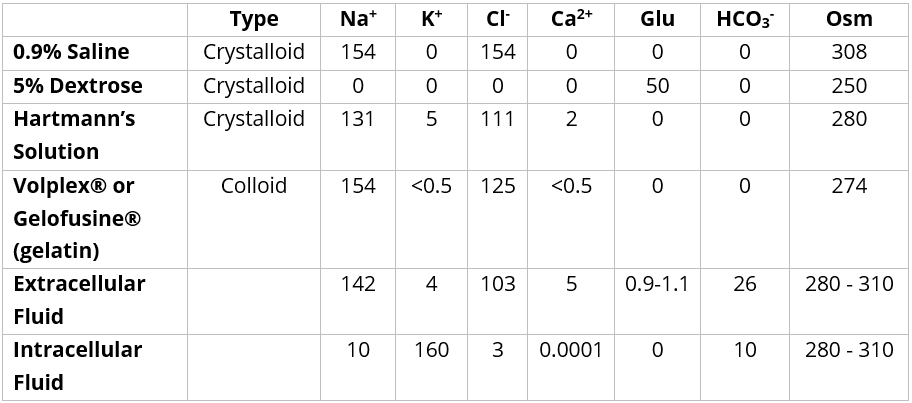

IV fluids can be broadly categorised in to two groups, crystalloids and colloids (as detailed in Table 2):

- Crystalloids – Crystalloids are more widely used than colloids, with research supporting the idea that neither is superior in replenishing intravascular volume for resuscitation purposes (with crystalloids also significantly cheaper). Therefore, crystalloids are used very commonly in the acute setting, in theatres, and for maintenance fluids.

- Colloids – Colloids have a high colloid osmotic pressure and theoretically should raise the intravascular volume faster than their crystalloid counterparts, yet clinical trials have not shown any significant benefit or effect in practice so their use in many hospitals is decreasing

More about intravenous fluid composition can be found in detail here.

Fluid Prescribing

Maintenance Fluids

As an example, let us say that our patient is a 70kg healthy male*. From the above section, we know in total, we need to prescribe fluids over 24 hours that provide 1750mL of water (70kg x 25mL/kg/day), 70mmol of Na+ (70kg x 1.0mmol/kg/day), 70mmol of K+ (70kg x 1.0mmol/kg/day), and 50g (50g/day) of glucose. Consequently, a typical fluid maintenance regimen is as follows:

- First bag: 500mL of 0.9% saline with 20mmol/L K+ to be run over 8 hours

- This provides all of their Na+, ~1/3rd of their K+, and a quarter of their water

- Second bag: 1L of 5% dextrose with 20mmol/L K+ to run over 8 hours

- This provides a further 1/3rd of their K+, and half of their water, as well as glucose

- Third bag: 500mL of 5% dextrose with 20mmol/L K+ to run over 8 hours

- This provides the remaining 1/3rd of their K+, and a quarter of their water, as well as glucose

*Providing the patient’s renal function is adequate and they are clinically euvolemic, these do not have to be replaced exactly but should be targeted, to permit ease of prescribing

Correcting a Fluid Deficit

Where the patient is initially dehydrated, you will need to correct this deficit with fluids, in addition to those prescribed as maintenance. However, in practice it is relatively uncommon to find a patient that is so profoundly dehydrated that this deficit needs to be calculated specifically. Instead, a subjective assessment is made based on clinical parameters, patient size, and any comorbidities.

Any reduced urine output (<0.5ml/kg/hr) should be managed aggressively, giving a fluid challenge and the clinical parameters, including urine output, subsequently rechecked (also ensuring any catheter is not blocked or patient not retaining urine)

The fluid challenge should be either 250ml or 500ml over 15-30mins, depending on the patient’s size and co-morbidities. For example a 120kg 30yr male may need >500 ml to make any difference to their intravascular volume, whereas in a frail 80yr lady with ischaemic heart disease and renal disease, 250ml may be more appropriate.

Replacing Ongoing Losses

Like much of fluid prescribing, there is a degree of subjective assessment in this aspect too. With reference to Table 1, one should assess if there are excess losses in any of the 4 secretions. Aspects to be assessed may include:

- Are there any third-space losses?

- Third-space losses refer to fluid losses into spaces that are not visible, such as the bowel lumen (in bowel obstruction) or the retroperitoneum (as in pancreatitis).

- Is there a diuresis?

- Is the patient tachypnoeic or febrile ?

- Is the patient passing more stool than usual (or high stoma output)?

- Are they losing electrolyte-rich fluid?

Common scenarios of electrolyte imbalances though fluid losses that may be encountered include dehydration (high urea:creatinine ratio and high PCV), vomiting (low K+, low Cl–, and alkalosis), or diarrhoea (low K+ and acidosis)

Ongoing Monitoring

When prescribing fluids, it is important to remember to regularly assess their fluid status, what they are managing orally, and amend their fluid prescription accordingly. Use your clinical assessment, nursing charts (fluid input-output charts ± daily weights) and U&Es to guide this.

Key Points

- Fluid management is a major part of junior doctor prescribing across many specialities

- Aims of fluid prescription can be divided into Resuscitation, Maintenance, Replacement

- A knowledge of the composition of each fluid type prior to their prescription is essential

- Ensure to regularly examine the patient following administration of fluids and reassess their requirements