Introduction

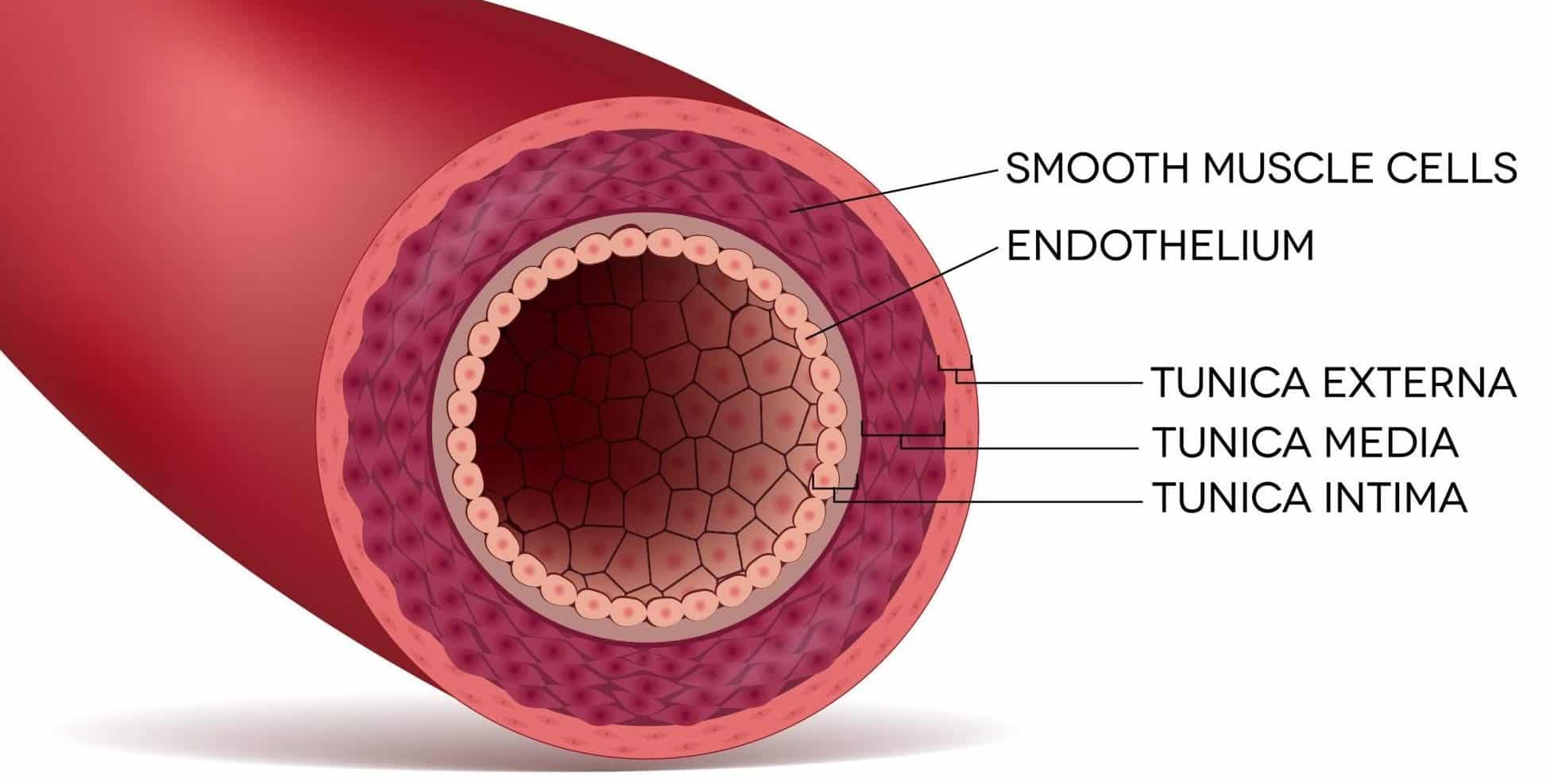

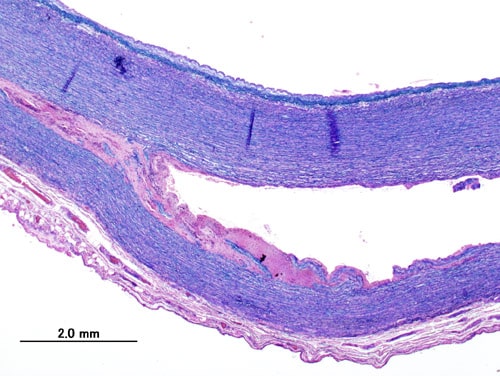

The wall of an artery (Fig. 1) consists of the tunica intima (innermost layer), tunica media (middle layer), and tunica adventitia (outermost layer). Acute aortic syndrome is is a disruption of these layers of the arterial wall, and is split into 3 subgroups: aortic dissection, penetrating aortic ulcer; and intramural haematoma.

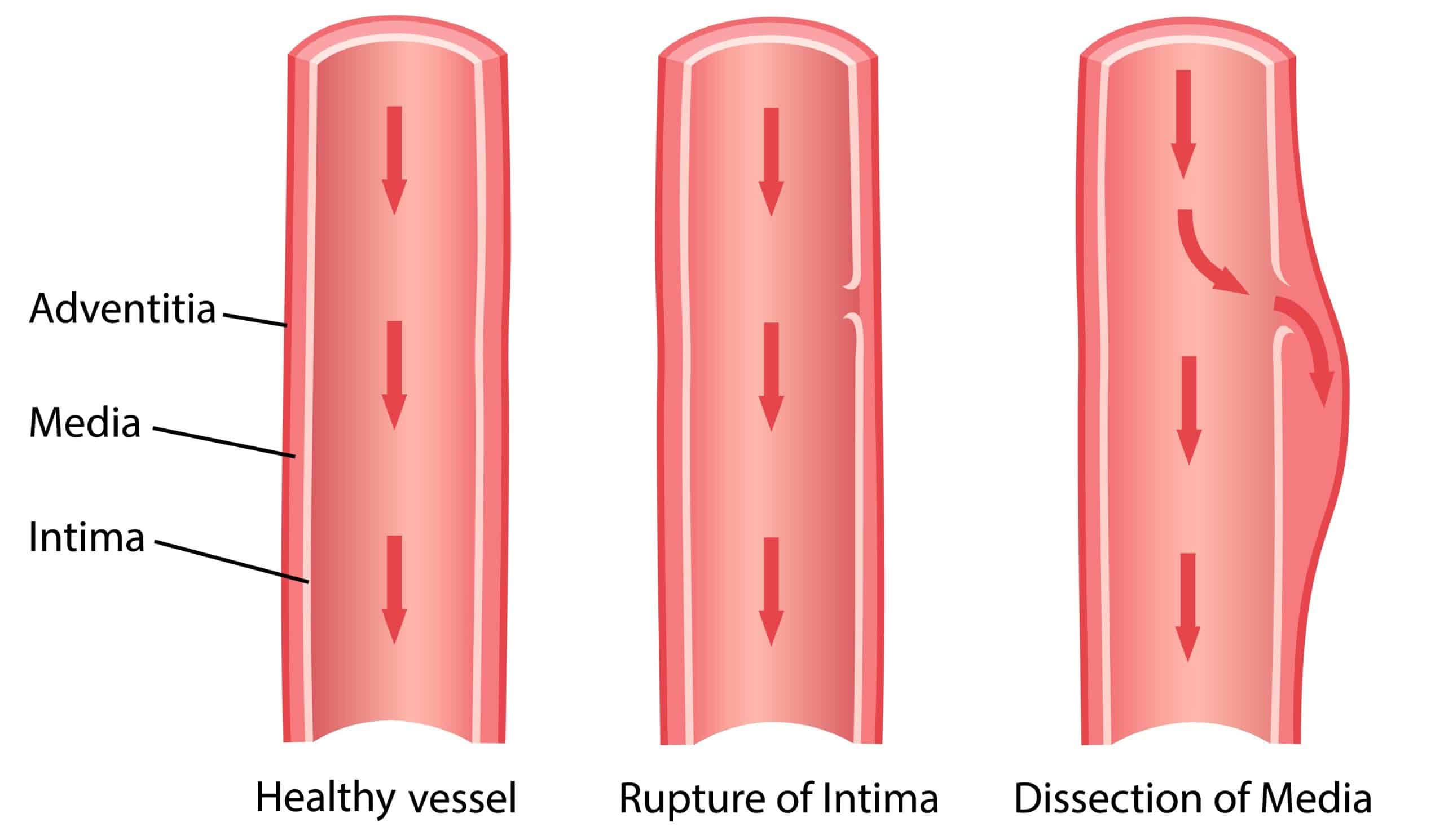

An aortic dissection is a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall (Fig. 2), causing blood to flow between and splitting apart the tunica intima and media. The majority of this article will focus on aortic dissection

Aortic dissections from the initial intimal tear can progress distally, proximally, or in both directions from the point of origin. Anterograde dissections propagate towards the iliac arteries and retrograde dissections propagate towards the aortic valve (at the root of the aorta)*.

They can be defined as acute (when diagnosed ≤14 days) or chronic (when diagnosed >14 days). They are more common in men and in patients with connective tissue disorders, and have a peak onset between 50-70yrs.

*Retrograde dissections can result in prolapse of the aortic valve, bleeding into the pericardium, and cardiac tamponade

Figure 2 – Aortic dissection is where blood enters the vessel wall via a tear in the tunica intima

A penetrating aortic ulcer is an ulcer that penetrates the intima and progresses into the media of the artery. This can progress to intramural haematoma, aortic dissection, perforation, or aneurysm formation.

An intramural haematoma is a contained aortic wall haematoma with bleeding in the media. This can progress to aortic dissection, perforation or aneurysm formation.

Classification

Aortic dissections are classified anatomically by two systems, DeBakey and Stanford.

Stanford Classification

The Stanford classification divides aortic dissection into two groups, A and B:

- Type A – involves the ascending aorta and can propagate to the aortic arch and descending aorta (i.e. DeBakey Types I and II) ; the tear can originate anywhere along this path

- Type B – does not involve the ascending aorta, occurring in any other part of the aortic arch and descending aorta (i.e. DeBakey Type III)

DeBakey Classification

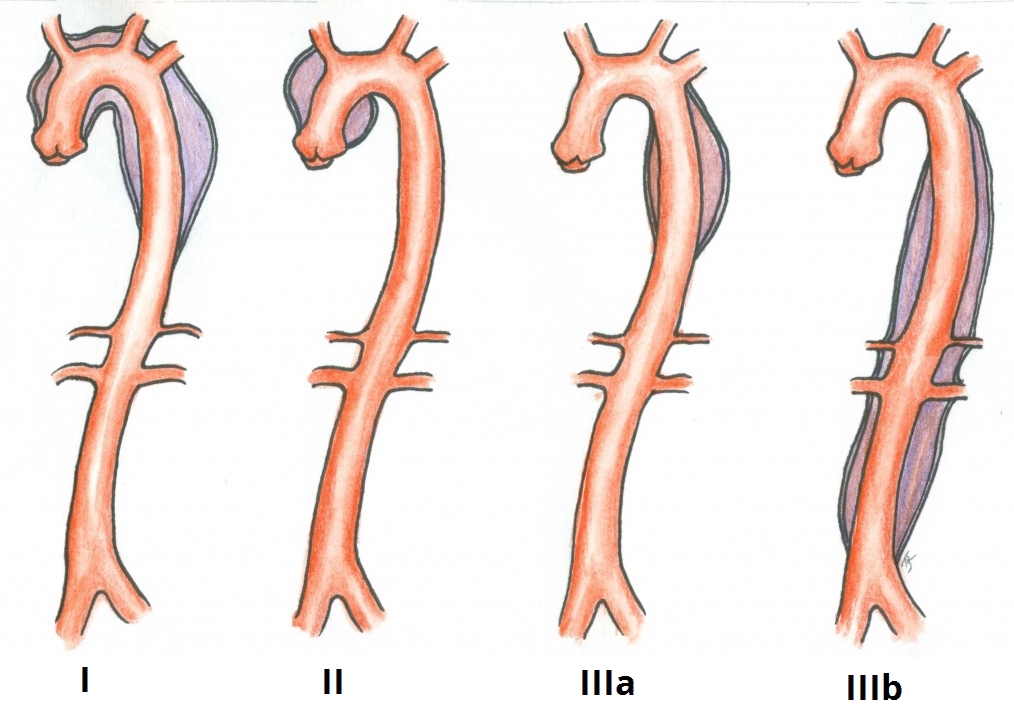

The DeBakey classification groups aortic dissections anatomically (Fig. 2):

- Type I – originates in the ascending aorta and propagates at least to the aortic arch

- They are typically seen in patients under 65yrs and carry the highest mortality, quoted at 1% per hour in the acute setting

- Type II – confined to the ascending aorta

- Classically in elderly patients with atherosclerotic disease and hypertension

- Type III – originates distal to the subclavian artery in the descending aorta

- Further subdivided into IIIa which extends distally to the diaphragm and IIIb which extends beyond the diaphragm into the abdominal aorta

Risk Factors

- Hypertension

- Atherosclerotic disease

- Male gender

- Connective tissue disorders* (typically Marfan’s syndrome or Ehler’s-Danlos syndrome)

- Biscuspid aortic valve

*As a general rule, younger cases often have associated connective tissue disorders, whilst older patients are more likely to have underlying hypertension or atherosclerosis.

Figure 3 – Histopathology of a thoracic aortic dissection, demonstrating the separation of the tunica intima and tunica media

Clinical Features

The characteristic presentation of an acute aortic aortic syndrome is of a tearing chest pain, classically radiating through to the back, yet the diagnosis is often challenging and many be a more subtle presentation.

The most common clinical signs include tachycardia, hypotension*, new aortic regurgitation murmur, or signs of end-organ hypoperfusion (such as reduced urine output, paraplegia, lower limb ischaemia, abdominal pain secondary to ischaemia, or deteriorating conscious level).

*Secondary to hypovolaemia from blood loss into the dissection or cardiogenic from severe aortic regurgitation or pericardial tamponade

Differential Diagnosis

A thoracic aortic dissection will often present as chest pain, a presenting problem that has multiple differential diagnoses:

- Myocardial infarction – classically crushing and central chest pain, with signs of cardiac ischaemia on ECG and / or raised serum troponin levels

- Pulmonary embolism – dyspnoea will be a prominent feature, with potential hypoxia present, can be confirmed with a CTPA (or V/Q scan)

- Pericarditis – classically pleuritic chest pain, with the ECG showing diffuse ST elevation, as well as potential pericardial rub on auscultation

- Musculoskeletal back pain – the patient will not present with systemic signs of shock and will be tender to palpation of the chest wall or paraspinal muscles

Investigations

Baseline blood tests (FBC, U&Es, LFTs, troponin, coagulation) with at least 4 units of packed red blood cells crossmatched. An electrocardiogram (ECG) should also be performed to exclude any cardiac pathology.

Imaging

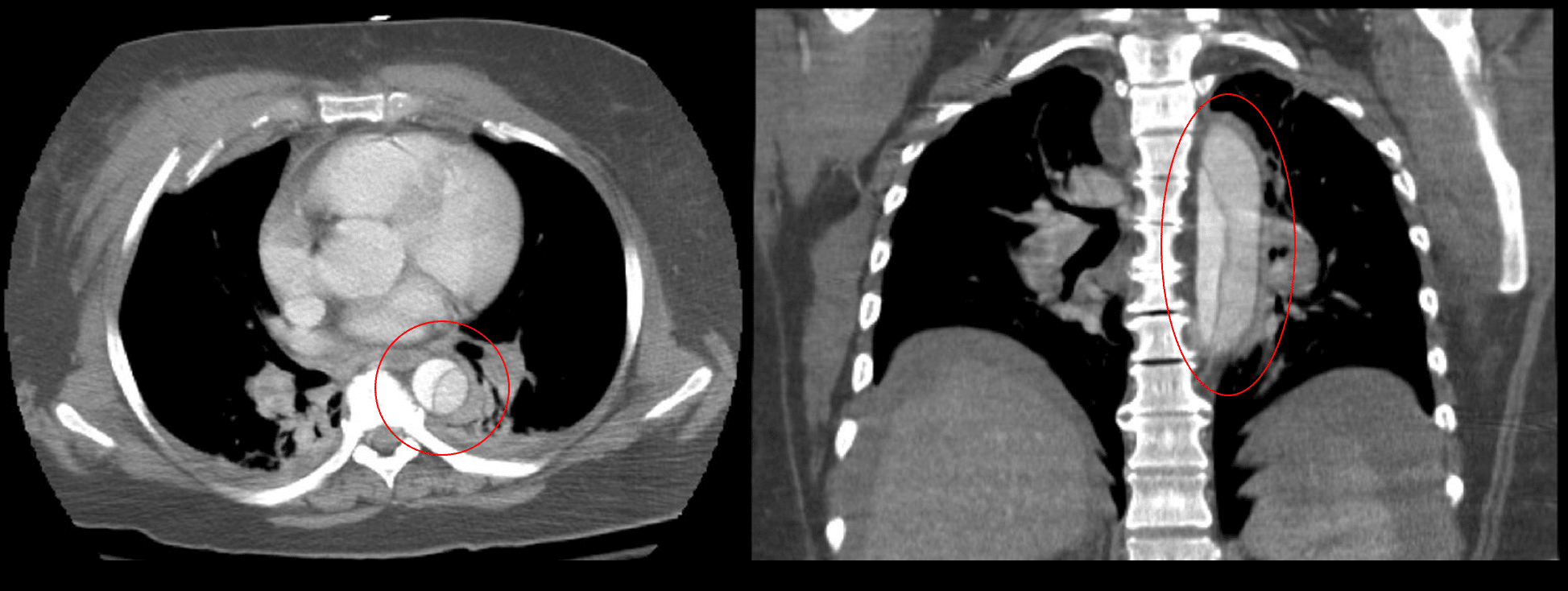

A computed tomography (CT) angiogram is recommended to diagnose acute aortic syndrome as first line imaging (Fig. 4). This will also allow for classification, establish the diagnosis and the anatomy of the pathology, and assist surgical planning.

A transoesophogeal ECHO can also provide useful information, especially in proximal or retrograde cases where there is concern regarding valvular involvement, but is operator dependent.

Management

Urgent initial assessment is required, as for any other critically ill surgical patient. Start high flow oxygen and gain IV access (x2 large bore cannulas); fluid resuscitation should be done cautiously*.

*In the setting of a rupture, then the target pressure should be sufficient for cerebral perfusion only, whilst in the setting of an uncomplicated dissection then the target systolic pressure should be kept below 110mmHg systolic.

Stanford Type A dissections should be managed surgically in the first instance under the care of a cardiothoracic surgery. They carry a worse prognosis of 1% mortality per hour in the initial phase, considerably worse than Type B dissections. Any uncomplicated Type B dissections can usually be managed medically. Penetrating aortic ulcer and intramural haematoma or also typically managed medically unless they progress.

Following initial management, all patients need lifelong antihypertensive therapy and surveillance imaging*, due to the high risk of developing further dissection or other complications.

*Imaging would usually be at 1, 3, and 12 months post-discharge, with further scans at 6-12 month intervals thereafter depending on the size of the aorta.

Type A Dissections

Type A dissections carry a high mortality if left untreated and these cases should be discussed urgently with a cardiac or vascular surgeon. They will most likely require transfer to a cardiothoracic centre.

The surgery involves removal of the ascending aorta (with or without the arch) and replacement with synthetic graft. If the dissection has damaged the suspensory apparatus of the aortic valve, this will also require repair.

Any additional branches of the aortic arch that are involved will require reimplanation into the graft (i.e. brachiocephalic artery, left common carotid artery, left subclavian artery), with long Type A dissections involving the descending and possibly abdominal aorta may require staged procedures.

Type B Dissections

Uncomplicated Type B dissections are best managed medically, with good survival rates. First line treatment is management of hypertension with intravenous beta blockers (labetalol) (or calcium channel blockers as second line therapy). The aim of this therapy is to rapidly lower the systolic pressure, pulse pressure, and pulse rate to minimise stress of the dissection and limited further propagation.

In the acute setting, endovascular repair is not recommended due to the risk of retrograde dissection, therefore medical management remains gold standard. Surgical intervention in Type B dissections is only warranted in the presence of certain complications, such as rupture, renal, visceral or limb ischaemia, refectory pain, or uncontrollable hypertension.

Type B dissections can go on to be chronic, with continued leakage into the dissection, even if a stent has been placed. The most common complication of chronic disease is the formation of an aneurysm. These present further surgical problems, with endovascular repair offering a better survival chance.

Complications

Any complications that arise depend on the site and spread of the dissection into the aortic branches, damaging end organs. Consequently, complications that can occur include:

- Aortic rupture

- Aortic regurgitation

- Myocardial ischaemia

- Secondary to coronary artery dissection

- Cardiac tamponade

- Stroke or paraplegia

- Secondary to cerebral artery or spinal artery involvement

Mortality remains high, with over 20% of cases dying before reaching hospital, however early diagnosis, intervention, and blood pressure control significantly improves prognosis.

Key Points

- An aortic dissection occurs following a tear in the intimal layer of the aortic wall causing blood to flow between the layers of the aortic wall

- Patients will classically present with a tearing central chest pain, radiating through to the back

- A computed tomography angiogram is the gold-standard first line investigation

- Type A dissections should be managed surgically whilst uncomplicated Type B dissections can initially be managed medically