Surgical suture materials are used in the closure of most wound types. The ideal suture should allow the healing tissue to recover sufficiently to keep the wound closed together once they are removed or absorbed.

The time it takes for a tissue to no longer require support from sutures will vary depending on tissue type:

- Days: Muscle, subcutaneous tissue or skin

- Weeks to Months: Fascia or tendon

- Months to Never: Vascular prosthesis

It is worth noting that regardless of suture composition, the body will react to any suture as a foreign body, producing a foreign body reaction to varying degrees.

In this article, we shall look the classification of suture materials, suture size, and the components of the surgical needle.

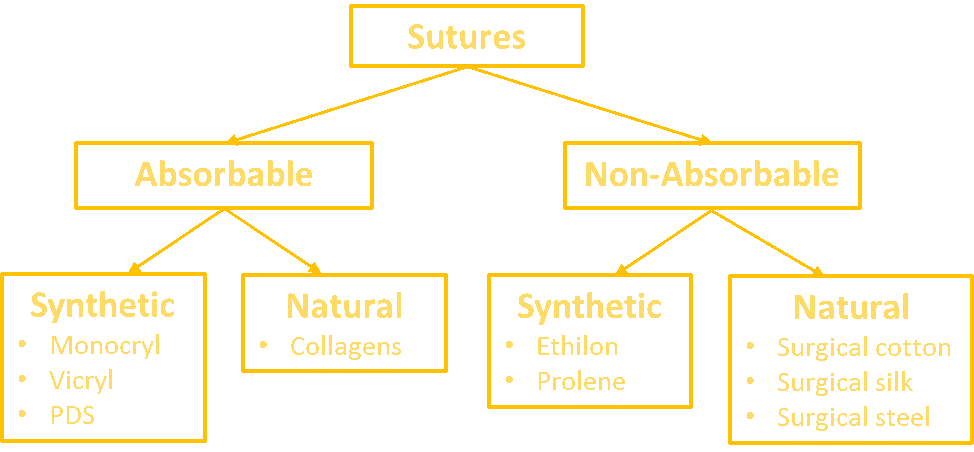

Classification of Suture Materials

Broadly, sutures can be classified into absorbable or non-absorbable materials. They can be further sub-classified into synthetic or natural sutures, and monofilament or multifilament sutures.

The ideal suture is the smallest possible to produce uniform tensile strength, securely hold the wound for the required time for healing, then be absorbed. It should be predictable, easy to handle, produce minimal reaction, and knot securely.

Figure 1 – The different classifications and sub-classifications of suture materials.

The suture type chosen vary much depends on the clinical scenario. For example, as a rough guide, a mass closure of a midline laparotomy may warrant use of PDS, a vascular anastomosis will probably require prolene, a hand-sewn bowel anastomosis may need vicryl, and securing a drain may need a silk suture.

Absorbable vs Non-Absorbable

Absorbable Sutures

Absorbable sutures are broken down by the body via enzymatic reactions or hydrolysis. The time in which this absorption takes place varies between material, location of suture, and patient factors.

Absorbable sutures are commonly used for deep tissues and tissues that heal rapidly; as a result, they may be used in small bowel anastomosis, suturing in the urinary or biliary tracts, or tying off small vessels near the skin.

For the more commonly used absorbable sutures, complete absorption times will vary:

- Vicryl rapide = 42 days

- Vicryl = 60 days

- Monocryl = ~100 days

- PDS = ~200 days

Non-Absorbable Sutures

Non-absorbable sutures are used to provide long-term tissue support, remaining walled-off by the body’s inflammatory processes (until removed manually if required).

Uses include for tissues that heal slowly, such as fascia or tendons, closure of abdominal wall, or vascular anastomoses.

Synthetic vs Natural

Suture materials can be further categorised by their raw origin:

- Natural – made of natural fibres (e.g. silk or catgut). They are less frequently used, as they tend to provoke a greater tissue reaction. However, suturing silk is still utilised regularly in the securing of surgical drains.

- Synthetic – comprised of man-made materials (e.g. PDS or nylon). They tend to be more predictable than the natural sutures, particularly in their loss of tensile strength and absorption.

Monofilament vs Multifilament

Suture materials can also be sub-classified by their structure:

- Monofilament suture – a single stranded filament suture (e.g nylon, PDS*, or prolene). They have a lower infection risk but also have a poor knot security and ease of handling.

- Multifilament suture – made of several filaments that are twisted together (e.g braided silk or vicryl). They handle easier and hold their shape for good knot security, yet can harbour infections.

| Suture Type |

Absorbable |

Non-absorbable | Monofilament |

Multifilament |

| Vicryl |

✓ |

✓ |

||

| PDS* |

✓ |

✓ |

||

| Monocryl |

✓ |

✓ |

||

| Nylon |

✓ |

✓ |

||

| Prolene |

✓ |

✓ |

||

| Silk |

✓ |

✓ |

Table 1 – Suture type and structure *PolyDioxanone Suture

Suture Size

The diameter of the suture will affect its handling properties and tensile strength. The larger the size ascribed to the suture, the smaller the diameter is, for example a 7-0 suture is smaller than a 4-0 suture.

When choosing suture size, the smallest size possible should be chosen, taking into account the natural strength of the tissue.

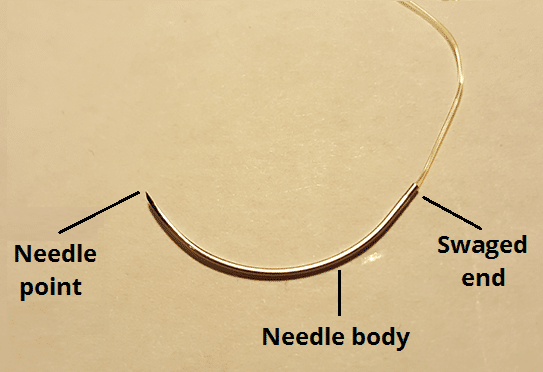

Surgical Needles

The surgical needle allows the placement of the suture within the tissue, carrying the material through with minimal residual trauma.

The ideal surgical needle should be rigid enough to resist distortion, yet flexible enough to bend before breaking, be as slim as possible to minimise trauma, sharp enough to penetrate tissue with minimal resistance, and be stable within a needle holder to permit accurate placement.

Commonly, surgical needles are made from stainless steel. They are composed of:

- The swaged end connects the needle to the suture

- The needle body or shaft is the region grasped by the needle holder. Needle bodies can be round, cutting, or reverse cutting:

- Round bodied needles are used in friable tissue such as liver and kidney

- Cutting needles are triangular in shape, and have 3 cutting edges to penetrate tough tissue such as the skin and sternum, and have a cutting surface on the concave edge

- Reverse cutting needles have a cutting surface on the convex edge, and are ideal for tough tissue such as tendon or subcuticular sutures, and have reduced risk of cutting through tissue

- The needle point acts to pierce the tissue, beginning at the maximal point of the body and running to the end of the needle, and can be either sharp or blunt:

- Blunt needles are used for abdominal wall closure, and in friable tissue, and can potentially reduce the risk of blood borne virus infection from needlestick injuries.

- Sharp needles pierce and spread tissues with minimal cutting, and are used in areas where leakage must be prevented.

The needle shape vary in their curvature and are described as the proportion of a circle completed – the ¼, ⅜, ½, and ⅝ are the most common curvatures used. Different curvatures are required depending on the access to the area to suture.

Key Points

- Suture materials can be classified in a variety of ways

- Choice of suture material is dependent on numerous factors, such as tissue type, infection risk, and personal preferences

- The surgical needle allows for the correct positioning of the suture material within a tissue