Introduction

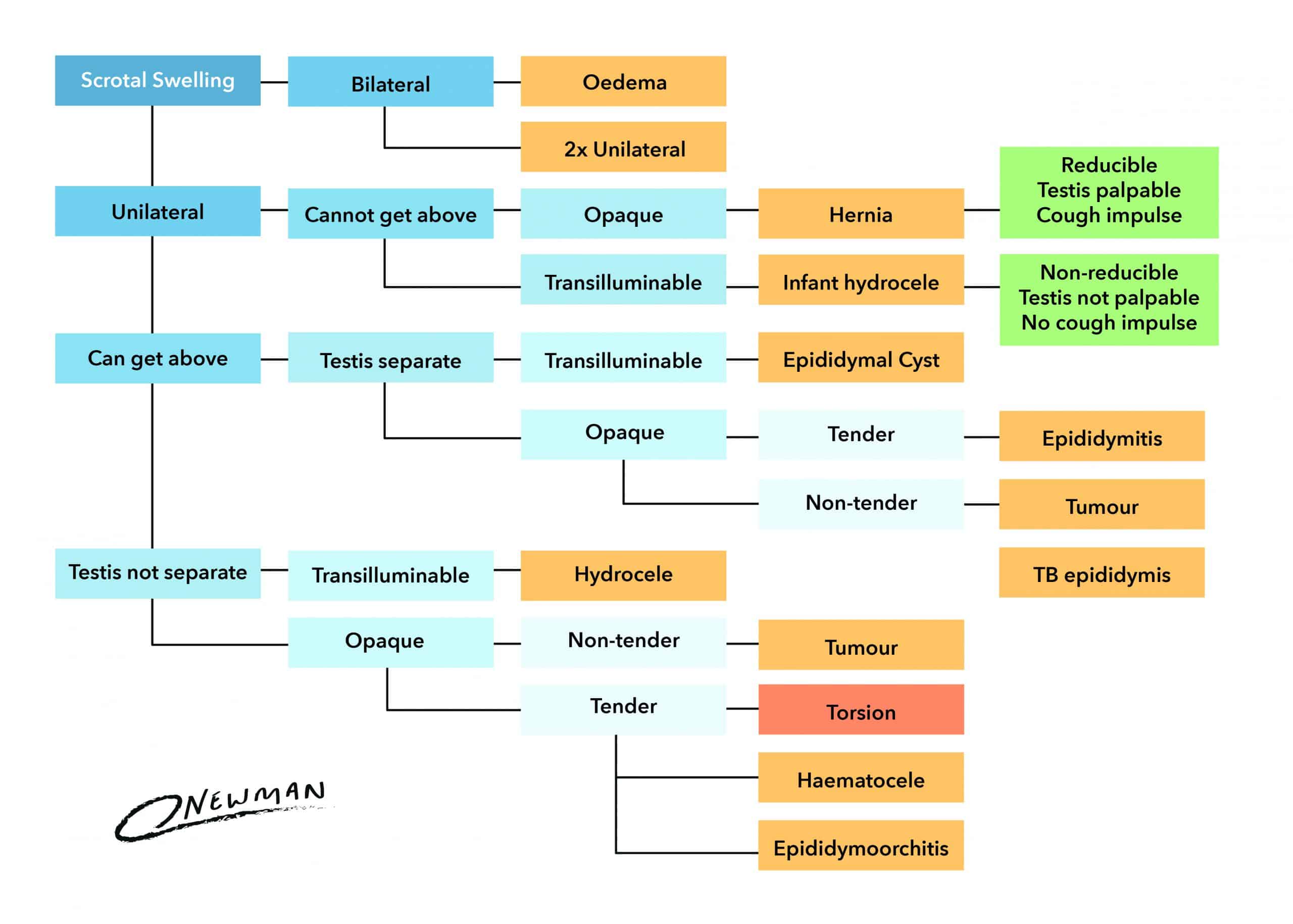

A scrotal lump is an abnormal mass or swelling within the scrotum. They can originate from either testicular or extra-testicular sources.

The presentation covers a wide range of pathology, therefore a good understanding of the differentiating features can aid in diagnosis, planning of suitable investigations, and the subsequent management.

Clinical Features

In the history, ensure to clarify time of onset, associated symptoms (especially pain), and previous episodes. In most cases, however, the diagnosis of a scrotal lump can largely be made from clinical examination alone.

Inspection of the lump should include the “6 S’s”, describing the Site, Size, Shape, Symmetry, Skin changes, and any Scars present.

When palpating the lump the examining clinician should comment on (CAMPFIRE is a useful acronym) Tenderness, Temperature, Transillumination, Consistency, Attachments, Mobility, Pulsation, Fluctuation, Irreducibility, Regional lymph nodes, and the Edge.

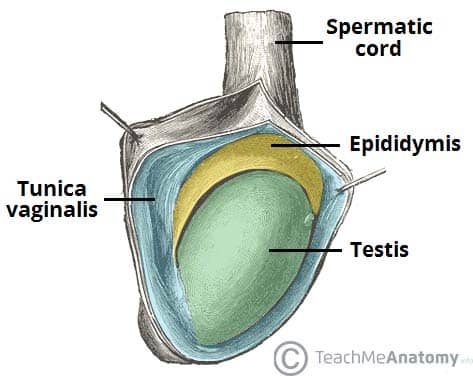

Specific to the scrotum, it is important to identify and separately palpate the testis, epididymis, and vas deference.

Investigations

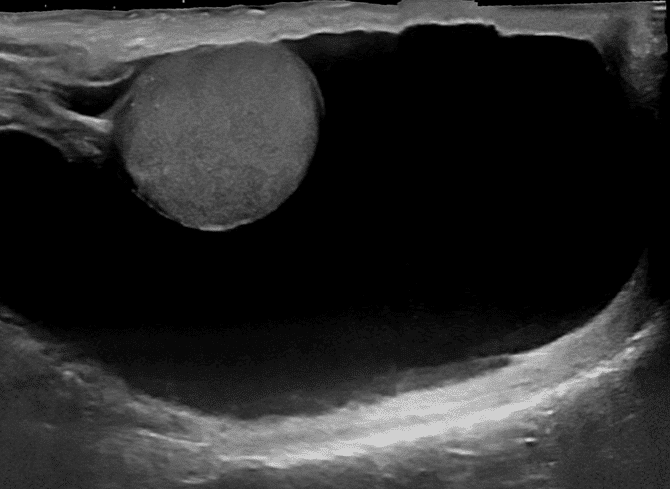

For the majority of scrotal lumps, especially those testicular in origin, an ultrasound scan of the scrotum is the first line investigation. Additional blood tests or further imaging may be warranted, depending on the suspected underlying cause

Investigating Suspected Testicular Cancer

Any mass arising from the testes will often need an urgent ultrasound scan to assess for testicular cancer. Unlike many other malignancies, a biopsy is not warranted for the diagnosis of testicular cancer (due to risk of seeding cancer), instead diagnosis is made purely on clinical features, ultrasound, and histopathological examination of the testis following orchidectomy.

In those where testicular cancer is suspected, blood tests for testicular tumour markers may also be sent, including lactate dehydrogenase (LDH), alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), and beta-human chorionic gonadotrophin (beta-hCG).

Differential Diagnoses

Scrotal lumps may be classified as being either testicular or extra-testicular in origin.

Figure 2 – Schematic showing the potential differential diagnoses of a scrotal lump

Extra-testicular

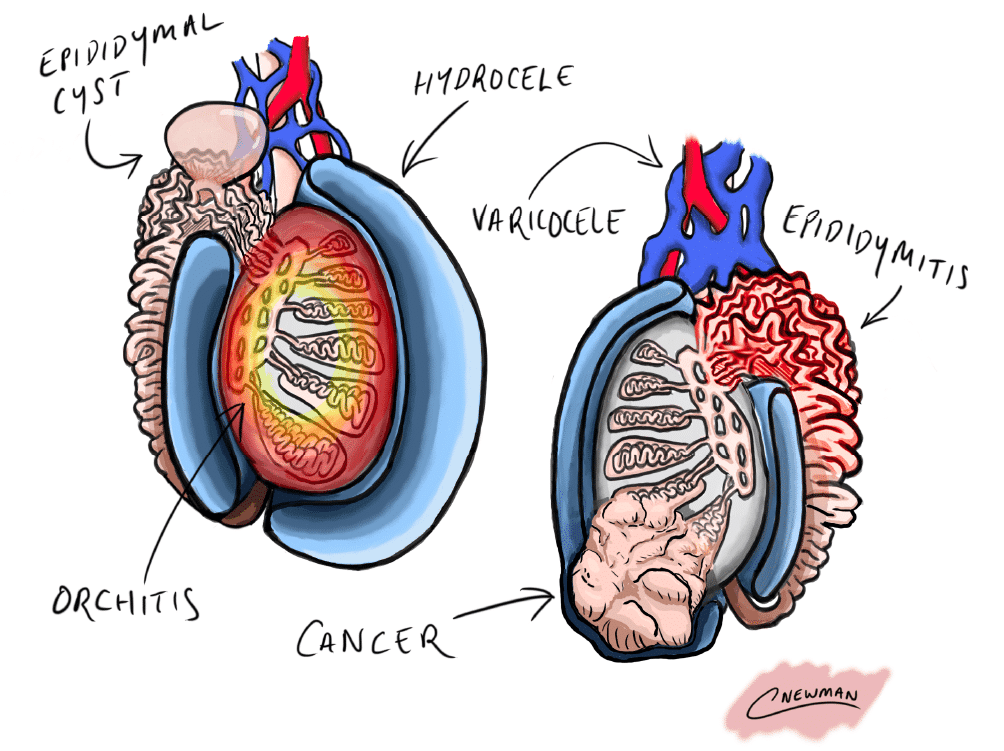

Hydrocoele

A hydrocoele is an abnormal collection of peritoneal fluid between the parietal and visceral layers of the tunica vaginalis enveloping the testis. They typically present* as a painless fluctuant swelling that will transilluminate, either unilateral or bilateral. Occasionally they can grow very large and cause discomfort when sitting and walking necessitating surgical management.

Congenital hydrocoeles affect up to 3% of male neonates and generally regress spontaneously by one or two years of age. No treatment is typically needed. In infants, they can be caused by a patent processus vaginalis requiring ligation to stop recurrence.

In older males, hydrocoeles may be primary (idiopathic) or secondary due to trauma, infection, or malignancy. Those presenting with a hydrocoele aged between 20-40yrs (or where the testis cannot be palpated) should undergo urgent ultrasound scan (Fig. 3).

*It is important to note that hydrocele can form along the spermatic cord and is a differential for lumps in the groin

Transillumination

Transillumination involves using a pen torch to shine light from behind a scrotal lump to observe whether the light travels through and illuminates the lesion.

The technique helps to assess whether a mass is fluid-filled or not, as fluid will transilluminate and solid masses will not. Hydrocoeles and large epididymal cysts will classically transilluminate.

Varicocoele

A varicocoele is an abnormal dilatation of the pampiniform venous plexus within the spermatic cord. They present as a lump, often described as feeling like a “bag of worms” or with a “dragging sensation”, and may disappear on lying flat. It is important to examine the patient lying down, standing up and whilst performing a valsava manoeuvre.

90% of varicocoeles are found on the left side as the spermatic vein drains directly into the left renal vein* (compared to the inferior vena cava on the right). They can cause infertility and testicular atrophy by increasing the intra-scrotal temperature; men who have a varicocoele and fertility issues should undergo semen analysis, with referral to a urology specialist if abnormal.

Red flag signs with a varicocoele are those of acute onset, right-sided, or remain when lying flat, and should be investigated urgently. Asymptomatic varicocoeles with no alarming features generally need no treatment.

Surgical management includes embolisation by an interventional radiologist and surgical approaches either open or laparoscopic approach for ligation of the spermatic veins.

*The abdomen should always be examined to exclude a renal tumour as the cause of a varicocoele, albeit rare

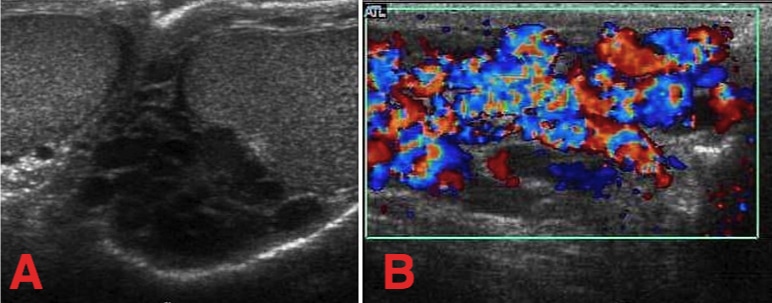

Figure 4 – An ultrasound demonstrating the dilated venous plexus of the varicocoele (A) without Doppler (B) with Doppler

Epididymal Cysts

Epididymal cysts (also known as spermatoceles) are benign fluid-filled sacs arising from the epididymis. They present as a smooth fluctuant nodule, found above and separate from the testis that will transilluminate, often they are multiple.

They are common scrotal pathology and are classically seen in middle-aged men. The cysts rarely cause symptoms, have no association to malignancy, and generally do not need treatment. In rare instances, they are very large or painful and therefore surgery may be required, but is best avoided in younger men as surgery may lead to infertility.

Epididymitis

Epididymitis is inflammation of the epididymis. It presents with unilateral acute onset scrotal pain and is one of the most common causes of scrotal pain in adults.

There may be associated swelling, erythematous overlying skin, and systemic symptoms such as fever. On examination, the epididymis is tender and pain may be relieved on elevation of the testis (Prehn’s sign).

Epididymitis is most commonly bacterial in origin, either STI-related organisms in sexually active younger males or enteric organisms in older males. Most cases can be treated with oral antibiotics and analgesia.

Inguinal Hernia

Inguinal hernia can pass into the scrotum via the external inguinal ring, entering the inguinal canal initially at the internal ring (indirect hernia) or through Hesslebach’s triangle (direct hernia). Passing into the scrotum they run alongside the spermatic cord.

On examination, you cannot “get above” an inguinal hernia within the scrotum (i.e. cannot palpate its superior surface). A cough may exacerbate the swelling and may disappear upon lying flat. All inguinal hernia should be assessed for strangulation or obstruction.

Testicular

Testicular Tumours

Whilst the vast majority of scrotal lumps are benign, with any testicular mass it is always vital to assess for features of testicular cancer. Classically, testicular tumours are described as painless lumps arising from the testis. In 5% of patients there is associated testicular pain complicating and delaying formal diagnosis. Examination may reveal a firm irregular mass, which does not transilluminate.

Testicular cancer is the most common malignancy in men aged 20-40yrs (more details found here). Suspected tumours need an urgent ultrasound scan for diagnosis, alongside tumour markers to aid in the diagnosis, staging, and monitoring to response of treatment for the cancer.

For lesions with a high index of suspicion for testicular cancer, radical inguinal orchidectomy may be required. The majority of patients will go onto receive chemotherapy following orchidectomy, with 5-year survival rates approaching 90% dependent upon grade and stage of the tumour.

Testicular Torsion

Testicular torsion is a twisting of the testis on the spermatic cord, leading to ischaemia. It presents with sudden-onset very severe unilateral scrotal pain, often with associated nausea or vomiting.

Torsion predominantly affects pubescent boys and may be associated with a ‘Bell-clapper’ deformity (high attachment of tunica vaginalis allowing rotation)

The affected testis is usually extremely tender, raised, and swollen, with a loss of cremasteric reflex (it rarely presents as scrotal swelling alone without any pain).

Testicular torsion is a surgical emergency and must be acted on immediately, with scrotal exploration and fixation of both testes, to prevent irreversible testicular damage. Salvage rates decline after 6-hours following onset of pain.

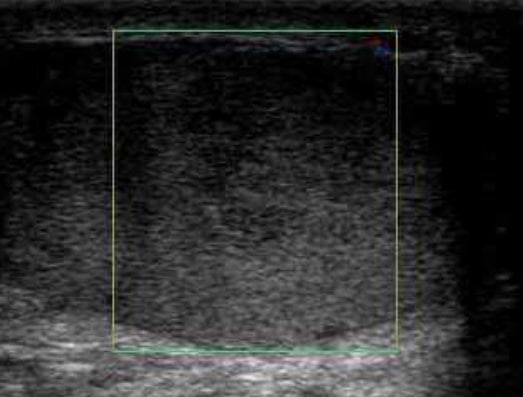

Figure 5 – Scrotal Doppler ultrasound showing no blood flow in a case of testicular torsion

Benign Testicular Lesions

Benign testicular lesions include benign leydig cell tumours, sertoli cell tumours, lipomas, or fibromas.

Orchitis

Orchitis is inflammation of the testis. It is rare in isolation*, with the main cause being the mumps virus, which often is preceded with a history of parotid swelling. Treatment is typically rest and analgesia. Rarely an intra-testicular abscess may form requiring drainage and occasionally orchidectomy.

*Cases of epididymo-orchitis should be treated as per epididymitis

Key Points

- A scrotal lump is an abnormal mass or swelling in the scrotum

- For the majority of scrotal lumps, an ultrasound scan of the scrotum is the best first line investigation

- Causes can be divided into extra-testicular and testicular causes

- Ensure to assess for features of malignancy in all cases of scrotal swelling and send for urgent investigation if suspected