Introduction

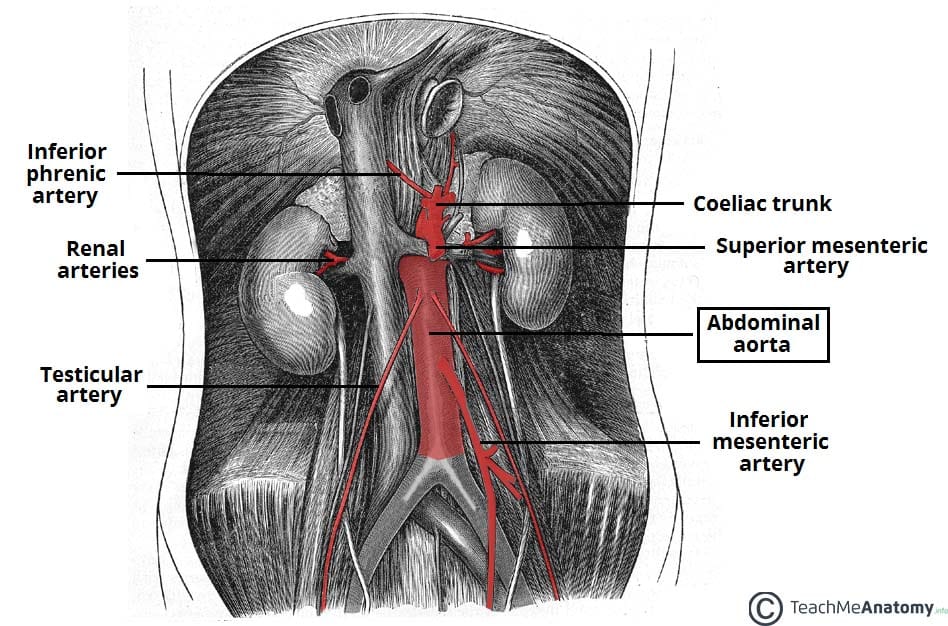

An aneurysm is defined as an abnormal dilatation of a blood vessel by more than 50% of its normal diameter.

An abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) is defined as a dilatation of the abdominal aorta greater than 3cm. In the UK, around 1 in 70 men over 65yrs have an AAA and over 3,000 deaths occur each year from a ruptured AAA.

It is an important condition to early identify and manage appropriately. Data has suggested that for every 8mm increase in aneurysm diameter, the relative risk of cardiovascular mortality increases by 1.34.

In this article, we shall look at the clinical features, investigations and management of abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Risk Factors

The aetiology of abdominal aortic aneurysm is largely unknown. Possible causes include atherosclerosis, trauma, infection, connective tissue disease (e.g. Marfan’s disease, Ehler’s Danlos), or inflammatory disease (e.g. Takayasu’s aortitis).

Risk factors for AAA include smoking, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, family history, male gender, and increasing age. Diabetes mellitus is a negative risk factor for AAA (the mechanism for this is poorly understood).

Clinical Features

Many abdominal aortic aneurysms are asymptomatic and are simply detected on incidental finding or screening.

Symptomatic patients with an AAA can present with abdominal pain, back or loin pain, distal embolisation resulting in limb ischaemia, or rarely as an aortoenteric fistula

On examination, a pulsatile mass can be felt in the abdomen (above the umbilical level), and rarely, signs of retroperitoneal haemorrhage may be evident.

A patient with a ruptured AAA may present with pain (abdominal, back, or loin) and a degree of shock or syncope, as discussed below.

Aneurysm Screening

In the UK, the National Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm Screening Programme (NAAASP) offer an abdominal ultrasound scan for all men aged 65yrs. Men screened for AAA have been shown to have an approximately 50% reduction in aneurysm-related mortality (albeit a limited influence on all-cause mortality), based on the Multicentre Aneurysm Screening Study.

Around 0.8% of those screened are diagnosed with an AAA, with 0.3% having an AAA large enough (≥55mm) to require direct referral for consideration of surgery. Most men with a detected AAA will spend 3 to 5 years in surveillance prior to reaching the threshold for an elective repair.

Differential Diagnosis

The main differential diagnosis in patients who present symptomatically is renal colic, due to presence of back pain with no other symptoms present. Other abdominal pathology to consider include such as diverticulitis, bowel ischaemia, degenerative disc disease, or ovarian torsion.

Investigations

In the routine outpatient setting, any suspected AAA should be initially investigated* by an ultrasound scan (USS)

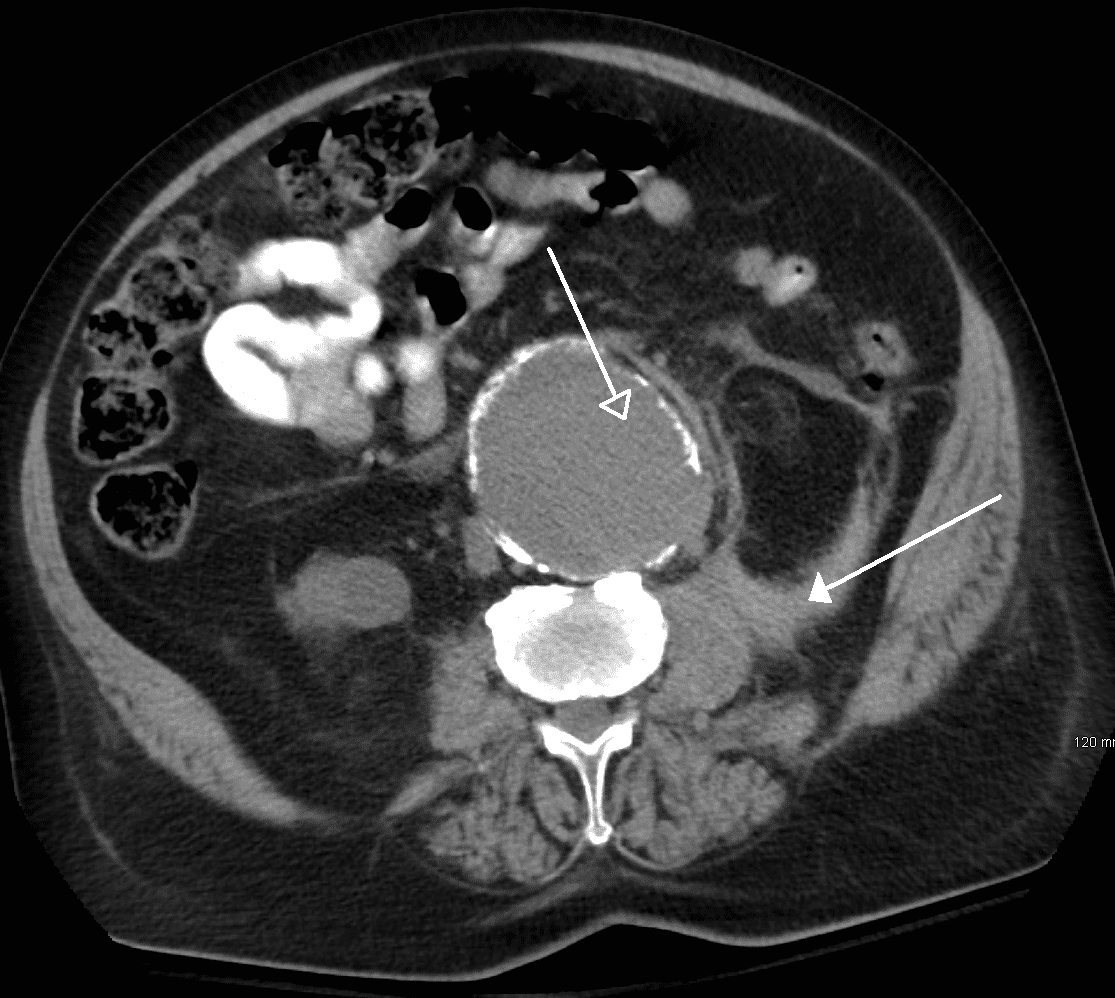

Once an USS has confirmed this diagnosis, a follow-up CT scan with contrast (Fig. 2) is warranted when at threshold diameter of 5.5cm. This provides more anatomical details in order to determine suitability for endovascular procedures.

*An AXR is not indicated as it will only rarely show an AAA if there is significant calcification of the arterial wall.

Management

Medical Management

Any AAA less than 5.5cm can be monitored via Duplex USS, as surgery prior to this diameter provides no survival benefit either for open repair or endovascular repair

- 3.0 – 4.4cm: yearly ultrasound

- 4.5 – 5.4cm: 3-monthly ultrasound

A patient with a small (3cm-5.5cm) AAA* has a 3% per year risk of cardiovascular mortality, hence cardiovascular risk factors should be reduced as appropriate:

- Smoking cessation (reduces rate of expansion and risk of rupture)

- Improve blood pressure control

- Commence statin and aspirin therapy

- Weight loss and increased exercise

*In the UK, any AAA >6.5cm requires notification to the DVLA and disqualifies from driving until repaired.

Surgical Intervention

Surgery should be considered for an AAA >5.5cm in diameter, AAA expanding at >1cm/year, or a symptomatic AAA in a patient who is otherwise fit*.

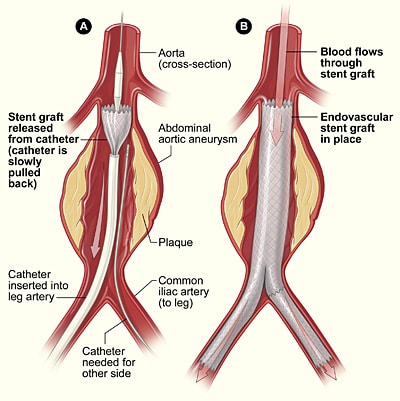

The main treatment options are open repair or endovascular repair, however both options have similar long term outcomes.

*In unfit patients, the AAA may be left until 6cm or more prior to repair, due to the significant risk of mortality from an elective repair compared to the risk of mortality if not repaired

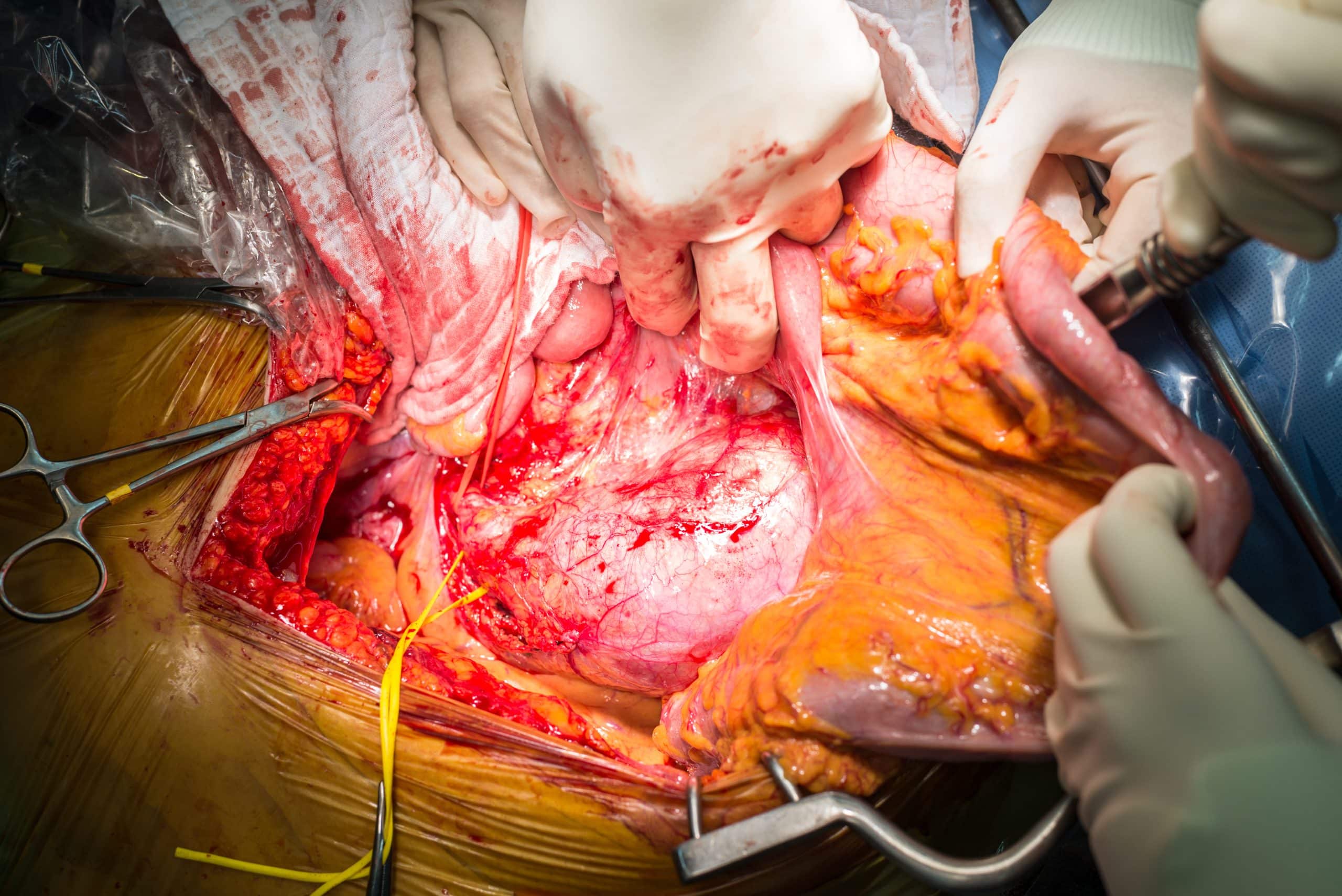

Open repair involves a midline laparotomy or long transverse incision, exposing the aorta, and clamping the aorta proximally and the iliac arteries distally, before the segment is then removed and replaced with a prosthetic graft (Fig. 3).

Figure 3 – A patient undergoing an open abdominal aortic aneurysm repair

Endovascular repair has better short term outcomes, however long term outcomes are better for those undergoing open repair. Choice of procedure depends on anatomical suitability for endovascular repair and patient fitness.

Endovascular repair does have an improved short term outcome in terms of decreasing hospital stay and 30 day mortality, yet has a higher rate of reintervention and aneurysm rupture. After 2 years the mortality for both procedures is the same, therefore in young fit patients an open repair may be more appropriate .

Endovascular Leaking

An important complication for EVAR is endovascular leak, whereby an incomplete seal forms around the aneurysm resulting in blood leaking around the graft.

Endoleaks are often asymptomatic hence regular surveillance (usually ultrasound unless a complication is noted) is needed. If left untreated, the aneurysm can expand and subsequently rupture. As such, any aneurysm expansion following EVAR warrants investigation for endoleak.

Endoleaks can be classified by the underlying mechanism causing the leak:

|

Classification |

Description |

| Type 1 | A leak occurs at the graft ends due to an inadequate seal, most common following thoracic aneurysm repairs; 1a = proximal, 1b = distal, 1c = iliac occlude |

| Type 2 | Sac filling occurs from a branch vessel, most common in AAA repairs (also termed retroleak), most resolve spontaneously. 2a = single vessel, 2b = two or more vessels |

| Type 3 | A leak occurs through a defect in the graft fabric. 3a = separation of sections of the graft, 3b = hole in the graft. |

| Type 4 | A leak occurs through the graft fabric due to the graft porosity, often occurs intraoperative and resolves with cessation of anticoagulants |

| Type 5 | Continued expansion of the aneurysm sac without any demonstrable leak on imaging (also termed endotension) |

Complications

The main complication of AAA is aneurysmal rupture, as discussed below. Other less common complications include retroperitoneal leak, embolisation, and aortoduodenal fistula

Ruptured AAA

The risk of AAA rupture increases exponentially with the diameter of the aneurysm, but the risk is also increased by smoking, hypertension, and female gender.

An AAA rupture can present with abdominal pain, back pain, syncope, or vomiting. On examination they will typically be haemodynamically compromised, with a pulsatile abdominal mass and abdominal tenderness.

Around 50% patients present with the ‘classic triad’ of ruptured AAA (flank or back pain, hypotension, and a pulsatile abdominal mass). Around 20% of AAA ruptures will rupture anteriorly into the peritoneal cavity (which are associated with a very poor prognosis), whilst 80% rupture posteriorly into the retroperitoneal space

Figure 5 – A ruptured AAA, as seen on axonal imaging on CT scan, rupturing into the retroperitoneal space

Management

Any suspected AAA rupture warrants immediate high flow O2, intravenous access (2x large bore cannulae), and urgent bloods taken (FBC, U&Es, clotting) with crossmatch for minimum 6 units.

Patients in shock should be treated carefully, as raising the blood pressure too much will potentially dislodge any clot and may precipitate further bleeding, therefore aim to keep the BP≤100mmHg (termed ‘permissive hypotension’, preventing excessive blood loss).

The patient should be transferred to the local vascular centre:

- If the patient is unstable, they will require immediate transfer to theatre for open surgical repair

- If the patient is stable, they will require a CT angiogram to determine whether the aneurysm is suitable for endovascular repair*

*The IMPROVE trial randomised patients suitable for EVAR or open AAA repair, showing no 30 day or 1 year difference in survival, but an increase in patients returning to their own homes, short hospital stay, and lower cost in the EVAR cohort

Key Points

- Most AAA are asymptomatic and are found incidentally or through screening

- Cases can be investigated by ultrasound scans, however CT imaging will be warranted when surgical intervention is considered

- Management warrants both tailored medical and surgical intervention, with definitive treatment either via open or endovascular repair

- A ruptured AAA needs urgent management and investigation, involving the suitable specialists as soon as possible